Ashoka Mody writes: The European Commissioner for Economic and Financial Affairs, Pierre Moscovici’s unnecessary—and unseemly—visit to Athens served to spotlight Europe’s corrosive politics.

Greece should not have been a member of the eurozone. But after the German Chancellor Helmut Kohl ensured Italy’s inclusion in May 1998, Spain and Portugal were waived in. So, the inevitable Greek entry came in 2002.

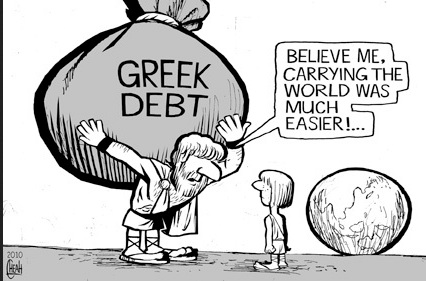

From October 2009, when Greek authorities acknowledged that they had lied about their fiscal accounts, to May 2010, the claim was that the problem would go away without external help. When eventually the troika—the European Commission, the European Central Bank, and the International Monetary Fund—put together a large bailout fund, the manifestly untenable claim was that Greece would repay its private creditors in full. In July 2011, the repayment terms on the troika’s debt were eased, but it was too little too late. Large losses were eventually imposed on private Greek creditors but not before harsh austerity caused an extraordinary slump in growth and lasting misery.

Today, the only right way forward is for the troika to allow Greece to repay its official creditors in, say, 100 years. This will effectively mean debt forgiveness but the cosmetics may help German leaders tell their citizens that they will be repaid.

But, of course, the system fights back all rational thinking. Ireland and Portugal will yelp that they also deserve more relief on their troika borrowings. More fundamentally, the forgiveness will directly contravene the Lisbon Treaty’s no-bailout provision, which prevents one member state from paying another’s debts. That would call into question the constitutionality of the European Stability Mechanism, which was approved by the European Court of Justice on the basis that the loans from the facility would be repaid with an “appropriate margin.”

At some point, a new fork in the road has to be taken. Today, Greece offers an opportunity to modestly test the eurozone’s pressure points. The stakes are high not just for the resolution of the crisis but for the future shape of Europe.

The same debates are being played out in Spain and will inevitably appear in Italy, which is being sucked into a debt-deflationary cycle. The discordant politics will make the resolution of economic challenges ever harder.

With Greece, the mistakes were legion. But a fresh start is now possible. Forgive the troika’s Greek debt. With a primary surplus—fiscal revenues above expenditures—and with now a very low public debt burden, Greece can start afresh with private creditors. The task of monitoring Greek fiscal accounts must shift from Mr. Moscovici’s office in Brussels—and from German officials—to private creditors.

Private creditors who will own newly-issued Greek debt will also unambiguously bear the burden of future defaults, ideally automatically and incrementally through sovereign “cocos”. A one-time violation of the no-bailout provision would be accompanied by a credible new no-bailout regime. And Greece will remain under pressure to reform and manage its public finances, but under a less politically-charged regime.