Mark Munn of Pennsylvania State University writes:

The jump in federal spending in response to the crisis of the coronavirus pandemic is not a new idea. Nearly 2,500 years ago, the people of ancient Athens had a similar plan – which succeeded in meeting the major threat they faced, but then tore Athenian society apart in a tangle of political recriminations after the crisis had passed.

As an historian of ancient Greece, the most telling parallel I see between current events and that long-ago past is the extreme partisan politics that befell Athens in 406 B.C.

A massive mobilization

In 406 B.C., Athens, a mega-power of the ancient Mediterranean that had built its economy on maritime trade, faccd a crisis. ,Despite recent successes in battle, deep partisan divisions over military leadership had left Athenian forces momentarily vulnerable to attack. Meanwhile, rival city-state Sparta had gained the backing of Persia and was building a navy that could challenge Athens’ control of the sea.

When the Spartans struck, they put the weakened Athenian fleet on the defensive, threatening to crush it and bring Athens to its knees.

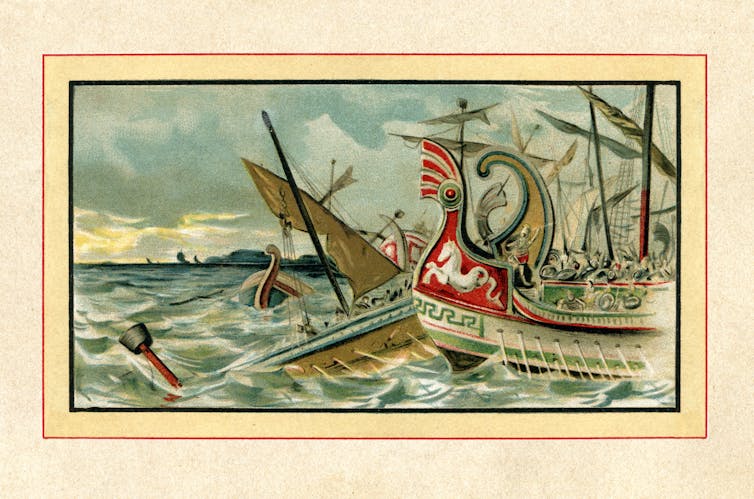

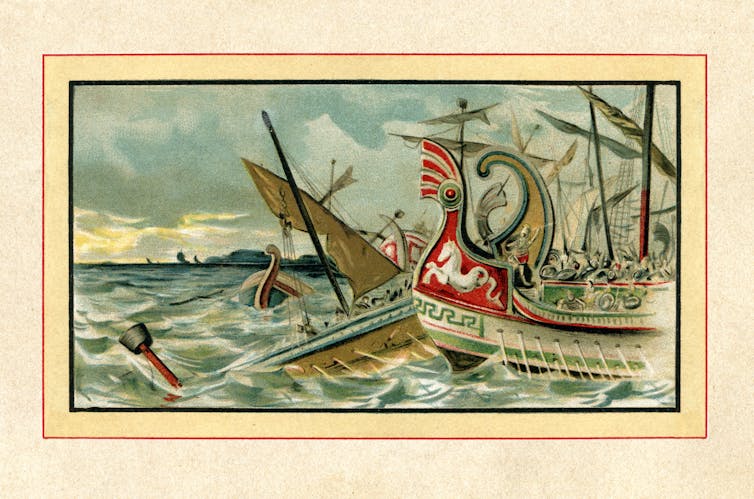

A steel engraving of the naval battle of Arginusae in 406 B.C.

In the face of near-certain disaster, the Athenians rallied to respond, accelerating a shipbuilding program already underway by mobilizing all the resources of their Aegean empire. A new tax was passed on personal wealth, and additional money was raised by melting down the golden statues of Victory that had been dedicated on the Acropolis. The resulting coins were spent buying Macedonian pine to make oars to power the triremes, the most advanced naval fighting ships the world had yet seen.

To pull the oars, all able-bodied Athenian men, including knights who normally did not serve in the navy, were called up. Even that was not enough. The Athenians offered citizenship to all resident foreigners and slaves who were willing to serve.

In a little more than a month, the Athenians had assembled a fleet of triremes powerful enough to challenge the Spartan fleet and regain control of the sea.

An enormous battle and victory

In midsummer, 406 B.C., the Athenian and Spartan fleets met in battle in the waters between the island of Lesbos and the coast of Asia Minor. It’s known as the battle of Arginusae, after the small islands off the Asian coast that served as a base for the Athenian fleet; today they are the Turkish islands of Garip and Kalem near the city of Dikili.

Athens won decisively, killing the Spartan commander and destroying nearly half his fleet. The victory was costly: Athens lost 25 out of their 150 triremes, each with a crew of 200 men. A few of the ships were sunk close to shore, and their crews were rescued. But most of the ships lost, carrying more than 4,000 men, were adrift farther out at sea, and went down in a storm that came up in the afternoon of the battle.

Athens was saved. Sparta pleaded for peace, but Athens rejected the terms offered, confident that its navy’s proven strength required no compromises with its foe. The fleet’s commanders, eight of the 10 generals elected annually by the people of Athens, were the heroes of the day. In the elections that followed in the weeks after that battle, six of the eight were reappointed to their commands.

The remaining two generals came home to undergo a mandatory part of public service to Athens: a review of their year in office and an audit of their spending on the public’s behalf.

Rowers in a Greek trireme are carved on a monument dating to close to the time of the battle of Arginusae.

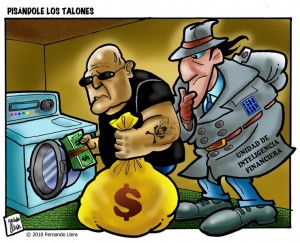

What happened to the money?

As Athens was preparing for battle, all the generals were entrusted with extraordinary amounts of money to finish and outfit ships, to hire and provision crews and more, all at top speed. In the haste to get the job done, not all the money was accounted for.

This was an opening for partisan prosecutors to investigate. One popular politician, a watchdog of the people’s money, filed charges of financial wrongdoing against one of the fleet’s generals.

The investigation revealed deeper evidence of financial abuse and mismanagement involving other generals as well as the original one accused. All the generals who had commanded during the battle were summoned back to Athens so their accounts could be audited. Four of the remaining six returned home; the other two chose not to return, fearing the consequences that awaited them at home.

An attempt to turn the tables

The generals faced prosecution from political opponents, including men who had served as ship captains during the battle and therefore would know about financial malfeasance in the preparations. If convicted, the generals faced having all their property confiscated and their Athenian citizenship revoked – changing them from national heroes to complete outcasts.

Together, the generals decided to defend themselves by attacking: They accused two of their most prominent opponents, popular political rivals who had been officers under their command, of failing to carry out their duties of recovering the shipwrecked crews. It was a serious charge, alleging responsibility for most of the battle’s casualties, that could have rendered the accusers ineligible to prosecute the generals.

The generals’ strategy backfired. Such serious new charges meant the whole matter was referred to the full Athenian assembly, the sovereign decision-making body of 5,000 to 6,000 Athenians. There, the two accused officers defended themselves against charges of dereliction of duty by producing the generals’ own report from after the battle, which made clear the storm – not human negligence – had made the rescues impossible.

That outraged the Athenians, who were angry at the generals for so transparently trying to escape their own accountability that they would accuse their officers of capital crimes. What began as an investigation of financial wrongdoing had become a contest over blame for the loss of life after the battle. The mood of the assembly determined the outcome, which was that all the generals were responsible for failing to save their men after the battle. The surviving records say nothing about the outcome of the charges of financial wrongdoing.

The verdict called for capital punishment: All six generals who had returned to Athens were put to death by hemlock poisoning.

A private grave relief in memory of an Athenian marine who died at sea; the date is uncertain but most likely from a decade or more after the battle of Arginusae. Athens, National Archaeological Museum, no. 752/Mark Munn, CC BY-ND

Everything began with enormous spending in response to an urgent crisis. Actions that seemed necessary at the peak of the emergency ended up as cover for misappropriations of public money.

But once the crisis passed, people saw those actions in a different light. Those who were found to have used the panic of the moment as an opportunity for personal gain ultimately paid the highest price. No doubt part of the reason they were judged so harshly was because so many of their fellow citizens had been forced to sacrifice their lives in a battle that enriched the powerful few.