Barry Eichengreen writes: Most obviously, Brexit would damage Britain’s export competitiveness. To be sure, ties with the EU would not be severed immediately, and the UK government would have a couple of years to negotiate a trade agreement with the European Single Market, which accounts for nearly half of British exports. The authorities could cut a bilateral deal like Switzerland’s, which guarantees access to the Single Market for specific industries and sectors. Or they could follow Norway’s example and access the Single Market through membership in the European Free Trade Association.

But Britain needs the EU market more than the EU needs Britain’s, so the bargaining would be asymmetric. And EU officials would most likely drive a hard bargain indeed, in order to deter other countries from contemplating exits of their own. The UK would have to accept EU product standards and regulations lock, stock and barrel, with no say in their design – and would be in a far weaker position when negotiating market-access agreements with non-EU partners like China.

In addition, Brexit would undermine London’s position as Europe’s financial center. It is quite extraordinary that the principal center for euro-denominated financial transactions is outside the eurozone. This attests to the strength of EU regulations prohibiting discrimination within the Single Market. But in a post-Brexit world, Frankfurt and Paris would no longer be prevented from imposing measures that favored their banks and exchanges over London’s.

The City is also an example of a sector that relies heavily on foreign labor. Upwards of 15% of workers in banking, finance, and insurance were born abroad. Attracting and retaining this foreign talent will become harder after Brexit, when EU workers moving to Britain will no longer be able to take their pension rights with them, and the other conveniences of a single labor market are lost.

Brexit could have more mundane, but highly noticeable, effects on Britain. Anyone who has spent time in the UK knows that the single greatest gain in the quality of life over the last generation has been in the caliber of the food. One shudders to imagine the culinary landscape of a UK abandoned by its French and Italian chefs.

Somewhat more weightily, a Britain that is just another middle power would be less able to project military and diplomatic influence globally than it currently is, working in concert with the EU. Although the UK would remain a member of NATO, we have yet to see how functional the Alliance will be in the era after US hegemony.

While the EU has yet to develop a coherent foreign and security policy, the ongoing refugee crisis makes clear that it will have to move in that direction. Indeed, this is the single most ironic aspect of the Brexit debate. After all, British public opinion first began to turn in favor of EU membership after the failed Suez invasion of 1956, which taught the country that, bereft of empire, it could no longer execute an effective foreign policy on its own.

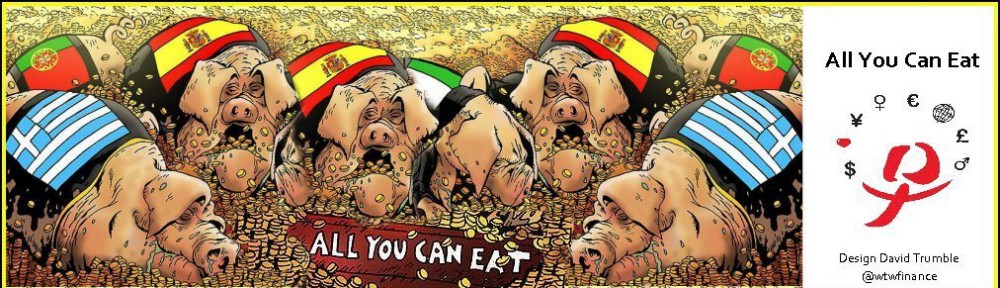

All of which leads one to ask: What can Brexit’s proponents possibly be thinking? The answer is that they are not – thinking, that is. The Brexit campaign is tapping into the same primordial sentiments as Donald Trump is in the US. Most Brexit supporters are angry, disaffected voters who feel left behind. Exposure to international trade and finance, which is what EU membership entails, may have benefited the UK as a whole, but it has not worked to every individual’s advantage.

So the disadvantaged are lashing out – against trade, against immigration, and against the failure of conventional politicians to address their woes. Fundamentally, a vote for Brexit is a vote against Prime Minister David Cameron, Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne, and the political mainstream generally.

The real problem, obviously, is not the EU; it is the failure of the British political class to provide meaningful help to the casualties of globalization. Within the last month, Work and Pensions Secretary Iain Duncan Smith resigned in protest over the government’s proposed cuts to welfare benefits. And on April 1, the minimum wage was raised. Maybe the voices of the angry and disaffected are finally being heard. If so, the Brexit debate will not have been pointless after all.