The rise of Trump and Samders and the Brexit vote in England show how desperate certain population groups are to be included in the work force again.

Betsey Stevenson writes: For all the encouraging headlines that the strong June jobs report has generated, it also illustrates a major challenge for the U.S. economy: Too many people are still not working or not even trying to find work.

The malaise can be remedied, if we can find the political will.

Despite the robust job growth of the past six years, people still aren’t participating in the labor force the way they used to. As of June, just 62.7 percent of the population had a job or was actively seeking one — up a bit from the previous month, but still almost 5 percentage points below the 2000 peak.

One explanation is demographic: As the population ages, a larger percentage will naturally be retired.

Still, even if we look at people in the prime working years of 25 to 54, participation is depressed. At the beginning of 2000, 84 percent of prime-age adults were in the labor force. Today, only 81 percent are.

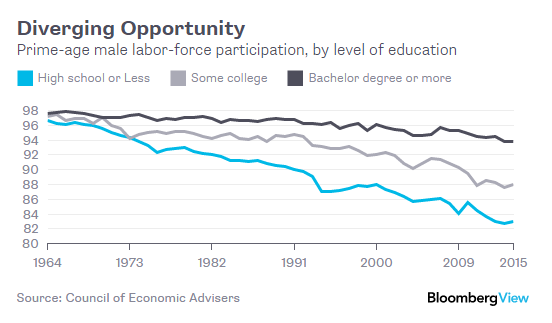

The Council of Economic Advisers finds that the decline in men’s participation is driven primarily by people with less than a bachelor’s degree — people who have seen very little wage growth for decades, an indication of the weak demand for their services. Such poor opportunities mean that when workers leave or lose a job, they struggle to reenter the labor force.

Unfortunately, some public policies have made things worse. Thanks to background checks, for example, the burgeoning ranks of men with criminal records — some for transgressions as minor as marijuana possession — are effectively locked out of the labor market.

Occupational licensing has also created barriers, requiring people to invest in a time-consuming and expensive process before entering fields ranging from haircuts and interior design to law and medicine.

It’s crucial that the U.S. create more opportunities for employment and promotion, particularly for lower- and middle-skilled workers.

One in five prime-age adults is sitting on the sidelines of the labor market today. We need to do more to bring them back.