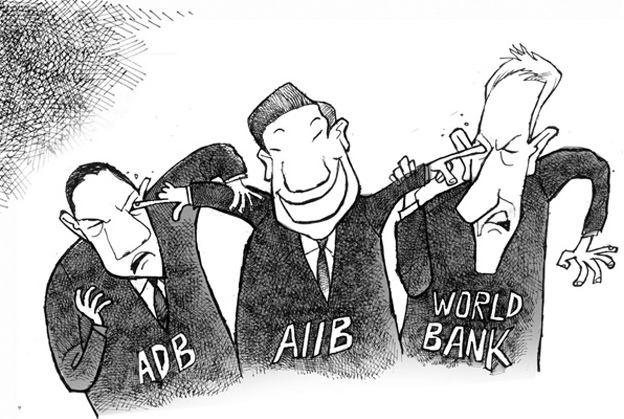

Hovering over the annual International Monetary Fund/World Bank meeting in Lima, Peru, were the China-inspired Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and New Development Bank (or “BRICS Development Bank,” as it was originally called). Will these new institutions behave like the World Bank or the more conventionally “bank-like” European Investment Bank (EIB)? Above all, will they be vehicles to promote – or, paradoxically, constrain – China’s interests?

Devesh Kapur writes” The reality is that over the next decade, these new institutions will not be huge lenders. The paid-in capital of each is $10 billion; so, even with an equity-to-loan ratio of 20% (the current floor for the World Bank), each will be able to lend only about $50 billion – not chump change, but hardly a game changer – unless they “crowd in” substantial private investment. What matters is that the larger emerging markets are putting substantial capital into institutions that will be dominated by China – an indication of how frustrated they are with the World Bank and the IMF.

In the 2015 financial year, the EIB lent more than twice the amount provided by the Bank, but with one-sixth the staff. Whether measured by flows (loan disbursements) or stock (loans outstanding), the World Bank is massively over-staffed.

When the Bank was formed, the key governance mechanism was a resident Board of Directors that reported to a Board of Governors. Over time, new offices proliferated.

Most of this bureaucratic growth was the result of pressure from developed countries.

The Bank’s extreme risk-averse culture reflects a rational response to critics who make a huge fuss about every project or program failure. Critics who take failures in commercial projects in stride find the Bank sloth-like compared with the private sector and become indignant when its projects fail. Yet, instead of making the case that risk is intrinsic to economic development and developing a risk-balanced portfolio of projects (and loans priced accordingly), the Bank pretends that it can be infallible. As a result, the best has become the enemy of the good.

Risk aversion has gone hand in hand with skewed institutional priorities, as is evident in the Bank’s budget. In the 2015 financial year, $623 million was allocated to “Client Engagement,” while nearly 1.5 times that amount, or $931.6 million, went to “Institutional, Governance & Administration” (the remaining $600 million, for “Program and Practice Management,” is ostensibly for supporting lending operations). Expenses for the Executive Board alone were $87 million. The Bank loudly proclaims the virtues of research – and then spends almost as much – $44 million – on “External and Corporate Relations.” The Future of the World Bank