Philippe Legrain writes: Greek parliamentarians have rejected the government’s candidate for president, triggering early elections scheduled for Jan. 25. Syriza, a radical-left coalition that wants to renegotiate the terms of Greece’s 205 billion euros’ worth of loans from eurozone governments, is leading in the polls.

Many fear that a showdown between eurozone authorities and a Syriza-led government bent on debt relief and ending austerity could revive the panic that almost destroyed the euro in 2012 and could even force Greece out of the 19-country currency union. The Athens stock exchange has plunged. Yields on Greek government bonds have soared. The cost of insuring against a Greek default has skyrocketed. But a Syriza victory on Jan. 25 may not be a calamity for Europe in the end. It may be a necessary step toward resolving a crisis that has been festering since 2009.

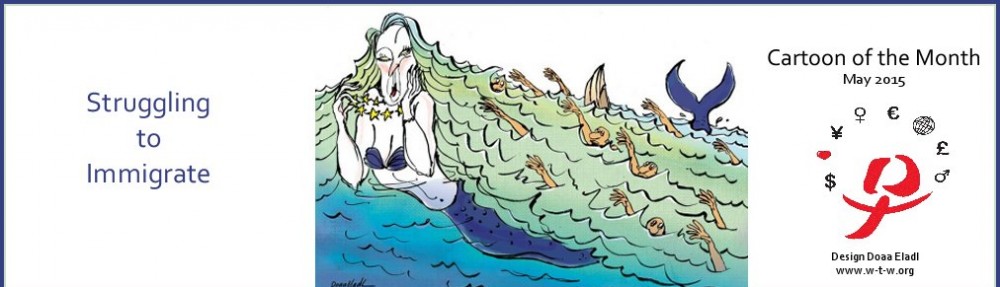

It’s not surprising that voters are angry with Prime Minister Antonis Samaras’s coalition government, which has implemented the brutal austerity demanded by the European Union and the IMF since Athens received its first bailout in 2010. Greeks have suffered six years of severe slump. The economy has shurnk by more than a quarter. Incomes have collapsed by nearly a third; many workers go unpaid. One in four Greeks — and one in two young people — is unemployed. The social safety net has been shredded. Crowds jostle for handouts at food banks. Some children are reduced to scavenging through rubbish bins for scraps. Hospitals run short of medicines. Malaria has even made a return.

Eurozone policymakers insist that Greeks have only themselves to blame for their plight and that the harsh treatment the policymakers imposed is working. But Greece’s reckless borrowing was financed by equally reckless lenders. First in line were French and German banks that lent too much, too cheaply — foolishly treating the Greek government as if it were as creditworthy as Berlin and encouraged by Basel capital-adequacy rules and European Central Bank collateral-lending rules that treated sovereign bonds as risk-free.

By the time Greece was cut off from the markets in 2010, its soaring public debt of 130 percent of GDP was obviously unpayable in full. Breaching EU treaties “no-bailout” rule they lent European taxpayers’ money to the insolvent Greek government. Poor Greeks were, in effect, consigned to a debtor’s prison.

While foreign banks that held on to their Greek bonds eventually took some losses in 2012, Greece’s EU creditors have bled the country dry. Thus eurozone banks and policymakers share responsibility for Greece’s plight.

Debt relief isn’t just a matter of justice. It’s an economic necessity. .Greece’s public debt is still a crushing 175 percent of GDP. With the economy gripped by deflation, the real debt burden is rising.

Without debt relief, the economy looks set to remain depressed. While it has scope for a bounce from its depths, a sustained recovery strong enough to make up lost ground, put Greeks back to work, and bring down debt is not in the cards. Even at its current annual growth rate, the economy would recover to its 2008 level only in 2030. Domestic demand is depressed by the debt overhang, while exports remain weak. Even with imports suppressed by crunched incomes, the country is running a whopping (and widening) trade deficit. The banking system is bust. No wonder businesses aren’t investing.

Nor has Greece fixed its fundamental flaws. Despite all the talk of reform, the EU’s priority has been austerity and wage cuts. The corrupt, clientelist political system remains intact. Politically connected businesses continue to have a stranglehold over cartelized markets. The rich still don’t pay their taxes. Re-electing Samaras and his New Democracy party won’t change any of that.

Nobody knows how an untested Syriza would behave in government. While its roots are on the hard left, Alexis Tsipras, its telegenic 40-year-old leader, has been softening his rhetoric and policy stance.

Should Merkel offer Greece debt relief as a gesture of solidarity? If the euro ultimately collapses, Germany will be blamed for wrecking Europe. Should she throw in a Marshall (or Merkel) Plan of investment for Greece and other crisis-hit countries that would also boost German exports?

Unfortunately, that is highly unlikely. Because of Merkel’s mistaken bailout of Greece’s private creditors in 2010, German taxpayers would lose out if Greece’s debt were cut. Since Germans self-servingly believe that as creditors they are virtuous, they feel no obligation to be generous to Greeks whom they view as sinful profligates. And Berlin is loath to set a precedent that could encourage others, notably the Irish, to seek relief for the bank debt unjustly imposed on them by the EU.

So Greece needs to stand up for itself and demand a negotiated write-down, backed by the threat of unilateral default. It can credibly do so: Since Athens has a substantial primary surplus, it would not need to borrow if it stopped servicing its debts. Syriza says it won’t write down bonds held by private investors, so Argentina-style legal entanglements aren’t a concern. With the bonds held by Greek banks untouched, the European Central Bank could scarcely refuse to accept them as collateral for liquidity. Meanwhile, German threats to force Greece out of the euro are probably bluster: Merkel has no legal right to deprive Greeks of the use their own currency, and it is implausible that unelected central bankers would dare splinter the eurozone. So Tsipras just needs to control his spending urges and stand his ground.