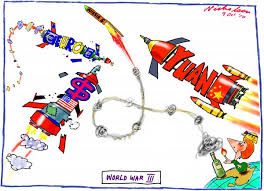

The Rocky Road to Globalization

The Economist reports: When the economics textbooks of the future are written, America’s ban on crude-oil exports will be a fine example of the perverse effects of protectionism. Similarly, a new decision by Barack Obama’s administration to allow American firms to sell some oil to Mexico will earn an honorable footnote in the story of the ban’s demise.

Geology, engineering, economics and politics are all at stake. In the fuel-hungry 1970s, America banned crude-oil exports in an effort to stabilize domestic prices. The country’s oil refineries are still configured to deal with the heavy, sour crude oil it used to import. Now, thanks to the shale revolution, American oil imports have plunged just as production has soared. Oil from shale is another kind of crude, light and sweet. It is not ideal for America’s refineries, which must make costly tweaks to deal with it. But the ban means this oil can’t be exported, either.

That archaic rule now keeps the price of America’s domestically produced oil, signalled by the West Texas Intermediate (WTI) benchmark, at a hefty discount—currently over $5 per barrel—to the world price. That has become particularly painful since OPEC’s decision in November to stop trying to curb production, which has sent prices tumbling. American oilmen are fuming: their potential export markets are being sacrificed, they argue, to the interests of America’s petrochemical industry, which enjoys artificially cheap feedstock thanks to the ban.

Others would benefit too. Free trade in crude would boost American output, investment, jobs, pay, profits and tax revenues—and GDP by $86 billion. With American crude bringing prices down, most likely the cost of fuel would fall a bit—for Americans, and also for other consumers.

The administration’s decision will test this theory. Mexico’s national oil company, Pemex, has long wanted to send its heavy crude to America, and import the same number of barrels of lighter American oil. The Commerce Department has now decided to treat Mexico as part of the domestic American market, as far as oil is concerned.

The extent of the exemption is still unclear. But this is not the first breach of the ban. The definition of what constitutes crude oil owes more to art (and bureaucratic fiat) than science. What is heavy crude? What is light?

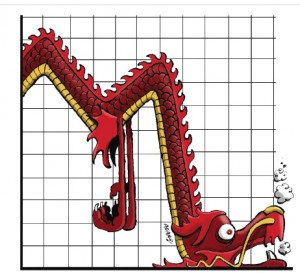

The ban undermines America’s moral authority at the World Trade Organisation, where the administration has berated China, for example, for imposing export bans on scarce minerals. Higher American crude-oil exports would also hurt petrostates such as Russia and Iran.

The details will still be tricky. America’s cossetted crude-oil consumers would be willing to see an end to artificially cheap raw materials in exchange for other concessions. These could include laxer environmental rules, or a change in an even more archaic law, the Jones Act, which bans foreign ships from carrying cargo between American ports. This law delights ship-owners and unions, but imposes a hefty cost on anyone wanting to send a tanker from, say, a refinery on the Gulf coast to a port in the north-east.

Such a wholesale solution to this elderly quirk in the world oil market may still be some time off. But by lowering trade barriers for Mexican oil, the Obama administration will make America richer, improve the functioning of the world oil market and highlight the potential benefits of still more dramatic reforms.