Companies with the highest percentage of female executives are, on average, 47% more profitable, 74% higher-performing on environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors, and 32% more transparent in ESG disclosure than those with the lowest, according to Foreign Policy Analytics’ groundbreaking Women as Levers of Change report. Through analysis of over 2,300 companies spanning 14 legacy industries around the world, female corporate participation is benefiting businesses from the boardroom to the bottom-line. And, we offer solutions for engaging these male-dominated, legacy industries to increase gender diversity within their sectors.

Category Archives: Finance

Fraud in the Time of Corona

The Economist writes:

When Bernie Madoff owned up to a $65bn Ponzi scheme in December 2008, it was not out of guilt. He knew the game was up. Three months earlier Lehman Brothers had imploded. The market meltdown sent clients clamouring to withdraw from his funds, leaving them depleted with many investors still unpaid. American regulators had not spotted the fraud, despite a tip-off years earlier. It was not them that did for Mr Madoff, but recession.

Booms help fraudsters paper over cracks in their accounts, from fictitious investment returns to exaggerated sales. Slowdowns rip the covering off. As Baruch Lev, an accounting professor at New York University, puts it, “In good times everyone looks good, and the market punishes you harshly for not keeping up.” Many big book-cooking scandals of the past 20 years emerged in downturns. A decade before the crisis of 2007-09 the dotcom crash exposed accounting sins at Enron and WorldCom perpetrated in the go-go late 1990s. Both firms went bust soon after. As Warren Buffett, a revered investor, once put it: “You only find out who is swimming naked when the tide goes out.” This time, thanks to a pandemic, the water has whooshed away at record speed.

Hell and low water

Much of the swimwear was already threadbare: a borrowing binge has strained many corporate balance-sheets. Some dirty secrets are beginning to come out. Take Luckin Coffee, which had expanded to take on Starbucks in China, attracting big-name investors like Blackrock and Singapore’s sovereign-wealth fund. On April 2nd the Nasdaq-listed Chinese chain announced an ongoing internal probe amid allegations that its chief operating officer and other employees may have fabricated over 2bn yuan ($280m) in sales. On April 14th Citron Research, a short-seller, accused gsx, a Chinese online-tutoring firm listed in New York, of inflating last year’s sales. In a statement gsx denied the allegations and said Citron’s report was misleading and “full of subjective maliciousness”.

These revelations have revived fears over the flaky corporate governance of Chinese firms listed on foreign exchanges, whose audits, conducted at home, China’s government makes it hard for outsiders to inspect. A gaggle of fraud-hunters like Citron and Muddy Waters, which outed Luckin, claimed numerous scalps after the first wave of such listings a decade ago. This time they are looking beyond China.

Blue Orca Capital, an Asia-focused fund targeting corporate “zeros”, expects opportunities to pop up in other emerging markets, Europe and America. “My entire career has been in a bull market,” says its founder, Soren Aandahl. “This is exciting.” Mr Aandahl is eyeing any firms with discrepancies between the amount of capital they need to raise and the cash their accounts say they are generating. Others are focusing on industries hit hardest by the pandemic, such as travel, entertainment and property.

Only a small minority of firms resort to outright fraud. Far more prettify profit-and-loss statements with accounting wheezes that fall in a grey area. This accounts for much of what John Kenneth Galbraith, an economist, called “the bezzle” and “psychic wealth”: gains that appear real but prove illusory.

In the bull market startups became masters of conjuring up novel metrics that flatter performance. WeWork’s “community-adjusted” earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation (ebitda) transformed a hefty loss for 2018 under Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (gaap) into a profit. Illegal? No. A red flag? Absolutely. Many investors turned a blind eye because they bought into what Mr Aandahl calls “the myth in the shareholder list”: all would be well if other high-profile backers were on board (as with Luckin).

Non-gaap adjustments have spread like wildfire through corporate accounts, making it harder to discern what numbers reflect a firm’s true financial position. The average number of non-gaapmeasures used in filings by companies in the s&p 500 index has increased from 2.5 to 7.5 in the past 20 years, according to pwc, a consultancy. In credit agreements analysed by Zion Research Group, the definition of ebitda ranges from 75 words to over 2,200. gaap is far from perfect, but some of the divergence from it has clearly been designed to pull wool over investors’ eyes. One study found that non-gaap profits were, on average, 15% higher than gaapprofits.

Playing around with earnings and revenue-recognition metrics is this generation’s equivalent of dotcoms using bots and other tricks to boost “eyeballs” 20 years ago, says Jules Kroll of k2 Intelligence, the doyen of corporate sleuths. “When an area is hot to the point of overheated, there is a growing temptation to juice the numbers.” In an ominous sign, SoftBank, a Japanese technology conglomerate which bet big on WeWork and dozens of other startups, said this week that it expects an operating loss of ¥1.4trn ($12.5bn) in its last fiscal year.

Besides exposing old schemes, the pandemic is likely to give rise to new ones. When economic survival is threatened, the line separating what is acceptable and unacceptable when booking revenues or making market disclosures can be blurred. Mr Kroll reckons that “amid such massive dislocation, some will inevitably cheat.”

Bruce Dorris, head of the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners, the world’s largest anti-fraud outfit, says the effects of covid-19 look like “a perfect storm for fraud”. It may engender everything from iffy accounting to stimulus-linked scams as thousands of firms—including bogus applicants—hustle for help. One fraud investigator points to private-equity-owned firms as potential targets. “There are lots of them, they are highly leveraged and they may not qualify for bail-outs because they have deep-pocketed sponsors,” he says. That increases the temptation to resort to unseemly practices. The ebbing tide is likely to reveal plenty of corporate nudity. That will not stop some businesses from taking up naturism

Women’s Role in Success

Companies with the highest percentage of female executives are, on average, 47% more profitable, 74% higher-performing on environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors, and 32% more transparent in ESG disclosure than those with the lowest, according to FP Analytics’ groundbreaking Women as Levers of Change report. Through analysis of over 2,300 companies spanning 14 legacy industries around the world, we show how female corporate participation is benefiting businesses from the boardroom to the bottom-line. And, we offer solutions for engaging these male-dominated, legacy industries to increase gender diversity within their sectors

A variety of market challenges are straining the bottom lines of a host of legacy industries. Changing global market conditions are intensifying competition among long-time industry rivals, while innovative new entrants shake up established business models. Consumers, particularly millennials and younger generations, are becoming more health-conscious and increasingly factoring environmental, social, and corporate governance considerations into their purchasing decisions, demanding less-harmful products and more sustainable corporate practices. Together, these factors are pushing companies to improve productivity and efficiency while evolving their business models toward addressing today’s critical environmental, social, and health challenges.

Increasing gender diversity could provide a means to respond to such pressures and enhance competitiveness and profitability. FPA’s company-level analysis reveals that a higher percentage of women in executive management is associated with higher profitability. Interviewees detailed how women are leading their organizations down new revenue-generating paths, advancing innovation in inertia-prone industries, and increasing transparency to build stakeholder trust.

Spread of Corona Virus in IMF Charts

Charts created by the International Monetary Fund trace the early stages of the Coronavirus pandemic:

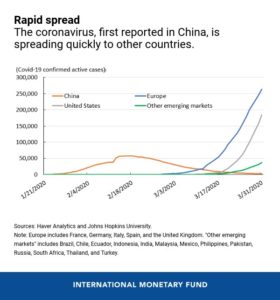

China was the first country to experience the full force of the disease, with confirmed active cases at over 60,000 by mid-February. European countries such as Italy, Spain, and France are now in acute phases of the epidemic, followed by the United States where the number of active cases is growing rapidly. In many emerging market and developing economies, the epidemic appears to be just beginning.

n Italy, the first country in Europe to be severely hit, the government imposed a national lockdown on March 9 to contain the spread of the virus. As a result, attendance in public places and electricity use have declined dramatically, especially in the northern regions where infection rates have been considerably higher.

n Italy, the first country in Europe to be severely hit, the government imposed a national lockdown on March 9 to contain the spread of the virus. As a result, attendance in public places and electricity use have declined dramatically, especially in the northern regions where infection rates have been considerably higher.

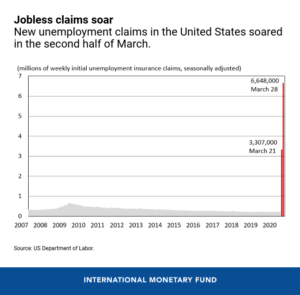

The economic consequences of the pandemic are already impacting the United States with unprecedented speed and severity. In the last two weeks in March almost 10 million people applied for unemployment benefits. Such a sharp and staggering increase has never been seen before, not even at the peak of the global financial crisis in 2009.

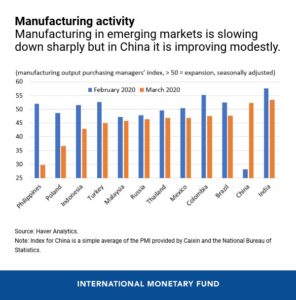

Disruptions caused by the virus are starting to ripple through emerging markets. After showing little movement early in the year, the latest indices from purchasing manager surveys (PMIs) are pointing to sharp slowdowns in manufacturing output in many countries, reflecting drops in external demand and growing expectations of declining domestic demand. On a positive note, China is seeing a modest improvement in its PMI after sharp declines early in the year, despite weak external demand.

The modest improvement in economic activity in China is reflected in daily satellite data on nitrogen dioxide concentrations in the local atmosphere – a proxy for industrial and transport activity (but also the density of pollution as a by-product of fossil fuel consumption). After a steep decline from January to February during the acute phase of the pandemic, concentrations have increased as new infections have fallen, allowing China to gradually relax its strict containment measures.

The recovery in China, albeit limited, is encouraging, suggesting that containment measures can succeed in controlling the epidemic and pave the way for a resumption of economic activity. But there is huge uncertainty about the future path of the pandemic and a resurgence of its spread in China and other countries cannot be ruled out.

Danger to National Security in Crypto Currency Transactions

Y. J. Fanusi, a former CIA officer and current senior fellow at the New American Center for Security writes: On March 2, the U.S. Department of Justice indicted two Chinese nationals for allegedly laundering cryptocurrency on behalf of North Korea. The laundering scheme ferreted away part of almost $250 million worth of virtual currencies stolen from a cryptocurrency exchange in 2018 by the North Korean-affiliated Lazarus Group. Through elaborate software programming, the two Chinese nationals, Tian Yinyin and Li Jiadong, converted much of the stolen cryptocurrency into regular currency at Chinese banks.

Y. J. Fanusi, a former CIA officer and current senior fellow at the New American Center for Security writes: On March 2, the U.S. Department of Justice indicted two Chinese nationals for allegedly laundering cryptocurrency on behalf of North Korea. The laundering scheme ferreted away part of almost $250 million worth of virtual currencies stolen from a cryptocurrency exchange in 2018 by the North Korean-affiliated Lazarus Group. Through elaborate software programming, the two Chinese nationals, Tian Yinyin and Li Jiadong, converted much of the stolen cryptocurrency into regular currency at Chinese banks.

The case exemplifies how cryptocurrency obfuscation tools and techniques are likely to play a growing role in financing threats to U.S. national security. As U.S. adversaries get more acquainted with blockchain technology, their hostile cyber operations are likely to rely increasingly on cryptocurrency activity. And rogue states are likely to become more innovative in using cryptocurrencies as they try to dampen the impact of U.S. economic sanctions.

A three-step formula for illicit finance is revealed: steal from exchanges, launder the digital currency and convert the tokens into real cash—hack, launder and cash-out.

The first step involved tactics familiar to anyone who has attended a basic cybersecurity awareness orientation. The Lazarus Group hackers tricked an employee of an unnamed exchange into clicking on an email that downloaded malware onto the employee’s computer. That malware gave the hackers remote access to the computer, allowing them to steal the private digital keys that controlled the exchange’s cryptocurrency wallets. They then withdrew $234 million worth of cryptocurrencies and sent them to digital wallets controlled by the Lazarus Group.

Next, the hackers sought to launder the funds by moving the crypto into wallets that would appear unrelated to the hacking. Most cryptocurrency transactions are visible for anyone to follow by browsing the online public ledger of transactions—the blockchain. Since they had a clear connection to the hacking, the Lazarus Group could not directly sell the stolen tokens for cash at most cryptocurrency exchanges. Instead, operatives in North Korea set up accounts at a variety of exchanges, using doctored photos and fake, non-North Korean identity documents. The hackers then transferred the stolen crypto using a programming script that moved the funds automatically through hundreds of newly created digital wallet addresses and eventually into North Korean-controlled accounts at the exchanges. Some of these funds were delivered to cryptocurrency exchange accounts held by Tian and Li, who spent the next several months doing additional laundering before finally converting crypto to cash.

The cash-out step was also multilayered. Tian and Li ran an unregistered cryptocurrency trading operation, converting stolen cryptocurrency into fiat currency and transferring it to customers in exchange for a fee. From July 2018 through April 2019, they traded with customers on various peer-to-peer exchange websites and opened up accounts at multiple Chinese banks to deposit their earnings from these trades. At one U.S.-based exchange, Tian transacted over 8,000 times, trading bitcoin for $1.4 million in iTunes gift cards. Overall, the pair made thousands of deposits into their Chinese bank accounts and laundered more than $100 million worth of ill-gotten crypto traceable to the Lazarus hack.

This laundering scheme probably posed no technical challenge for North Korea. The open-source software programs the hackers used to create thousands of digital wallets in minutes are freely available online. These wallets are called “unhosted” or “non-custodial” wallets because they are not controlled by any exchange and cannot be blocked or shut down by a third party. Unlike the wallets used at exchanges, there is no need to provide any ID to acquire them. They are truly pseudonymous instruments.

And the scheme was likely cost efficient. The Lazarus group funded part of their broader cyber operations with the hacked cryptocurrencies. Using funds sent to their unhosted wallets, the operatives paid in bitcoin for website hosting, domain names and virtual private networks. Those services supported additional phishing campaigns, allowing the hackers to create fake websites that delivered malicious code to other exchanges—a vicious cycle of laundering and hacking.

As the North Korean case highlights, two things enable cryptocurrency laundering: easy access to unhosted wallets and the existence of cryptocurrency exchanges around the world with lax anti-money laundering (AML) measures.

Unhosted wallets pose an even thornier challenge. The ability for parties to transact digitally without a financial intermediary is the primary breakthrough of cryptocurrency technology. Unhosted wallets lower the barrier to financial services, bringing financial inclusion to unbanked and underbanked populations—though there is little data to support this assertion. Ultimately, financial authorities cannot realistically ban open-source software, so the current regulatory framework targets the on and off ramps where people cash out: cryptocurrency exchanges. Regulators tolerate the loophole of unhosted wallets because—for the time being—crypto has minimal purchasing value unless converted to fiat currency.

Legal and regulatory activity surrounding crypto and illicit finance will likely grow in the coming years as U.S. adversaries rely increasingly on cryptocurrency operations to fund threats.

This nexus among cryptocurrencies, state-sponsored cyber operations and U.S. national security has also surfaced with other adversaries. Russian military intelligence officers laundered and spent $90,000 worth of crypto to support their cyber operations and information warfare during the 2016 U.S. presidential election.

National security officials must get smarter on cryptocurrency for the U.S. to combat the money laundering typologies emerging on blockchains rather than in banks. This means training analysts on blockchain technology and getting them acquainted with developments in the crypto space. And financial regulators will have to continually assess whether exchanges are effectively managing the risks from unhosted wallets. If they do not manage them, new regulatory frameworks may be needed to plug crypto’s regulatory gaps. This could involve developing guidelines for how much exchanges can interact with unhosted wallets. But any new rules need not be conceived by regulators in isolation. Blockchain proponents should also innovate to create products that advance the promises of this technology while mitigating the risks from bad actors. As the recent indictments show, U.S. adversaries are working creatively to exploit the loopholes. The U.S. needs to bring its A-game to meet this emerging threat.

Our Hero Elizabeth Warren Watches the New Slush Fund for Corona

As a Senator and expert on banking, Elizabeth Warren has provided an indispensable oversight to government and banking activities. It is not surprise to find her at the forefront of the massive spending proposed to combat the corona virus in the US.

Before Elizabeth Warren was a senator from Massachusetts and a Democratic presidential candidate, she ran the Congressional Oversight Panel that was in charge of overseeing the $700 billion Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) bailout that Congress approved after Wall Street crashed in 2008. In that capacity, Warren, then a Harvard law professor, kept a close watch on where the money was going and crafted public reports that disclosed that the Treasury Department had overpaid $78 billion for assets it bought from failed banks and that large chunks of the money were not being used well.

Last month, Congress passed a $2 trillion coronavirus bailout and assistance bill, and it contains a $500 billion fund from which the Trump administration, at its sole discretion, can dole out money to big corporations in distress. What’s the best way to monitor this flow of billions? Warren, no surprise, has some ideas.

The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, Warren notes, has four overall parts: sending money to hospitals and other health care facilities, expanding unemployment benefits, providing assistance to small businesses, and establishing what she agrees is a $500 billion “slush fund” for large corporations. There is also money in the bill for education, food security, and state and local government responses to the crisis. Donald Trump and his administration may use this money to “reward their political friends and punish their political enemies.” Warren points out, “I spent a lot of time in the negotiations [over the bill]…to try to get at least some curbs on how the money is spent and some oversight. Republicans basically said this is going to be the price of getting money to our medical providers, getting money to people who are unemployed, getting money to small business: ‘You guys are going to have to go along…with this slush fund for giant corporations.’”

The oversight provisions in the measure do include a special inspector general for pandemic recovery, who will track all loans and expenditures made from the $500 billion fund, and a congressional oversight commission, similar to the one Warren ran years ago, which will monitor this spending and evaluate its impact. But Warren points out the commission will only be as strong as its members, who have yet to be appointed:

When Warren was the cop on the bailout beat, she generally had the support of a Democratic Congress and the Obama administration. That won’t be the case this time around. Trump has already said he has the right to block the new special IG from sharing information with Congress and the public. And the CARES Act contains no provisions that allow any outside review of expenditures or loans before Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin okays them. Whatever he (or Trump) decides, goes.

In this environment—with a president hostile to transparency and accountability—what can be done to cast sunlight onto Mnuchin handing out $500 billion in taxpayer dollars to big companies?

Warren recommends: 1. Be consistent in talking about this every single day. We can’t let this just drop off the radar screen. Remind people the slush fund exists. 2. Dig into individual pieces and tease out whatever information we can. 3. Shout about any bad examples that turn up. Point out this is taxpayer money, money that could have been used for personal protective equipment or health care professionals…money that could have been used to help small business and to help people who are unemployed.

With no clawbacks allowed the only recourse is to jump on every piece of information that comes out because that influences the next decision that gets made. The only restraint is “public opinion.

Warren’s tips essentially boil down to this: pay attention, pay attention, pay attention Use crowdsourcing oversight.

W-T-W.org welcomes any comments and suggestions to create crowdsourcing oversight.

How Much can Federal Reserve Policy Impact the Covid-19 Economy?

The San Francisco Federal Reserve looks at Uncertainty and evaluates its impact on the economy.

Uncertainty is a fact of life. Long-term economic decisions are challenging because they often have long-lasting consequences and require people to make some pre-commitments. Once these decisions are made, they can be costly to reverse. For example, when people buy a house, they need to make an assumption about their future employment status and whether they will have the means to make mortgage payments. Similarly, when a business contemplates investing in a new product line, the manager must make assumptions about the strength of the economy several years ahead and how much consumers will be willing to pay for that new product. When times are uncertain, households and businesses may postpone consumption and investment decisions until they have more clarity about what lies ahead.

One indicator of uncertainty is the Chicago Board Options Exchange Volatility Index, or VIX, which measures investors’ perceptions of the 30-day-ahead volatility of the S&P 500. The VIX daily series has spiked several times since 2007. It jumped to its previous record high in November 2008, in the midst of the global financial crisis. The VIX also shot up in the fall of 2018 during a tense period of trade negotiations between the United States and China. Most recently, the COVID-19 pandemic and uncertainty about its negative impact on the world economy have ramped up the VIX to levels surpassing but comparable to those during the 2007 – 2008 global financial crisis.

In theory, heightened uncertainty can raise unemployment because a job match represents a long-term employment relationship and hiring decisions are costly to reverse. When uncertainty rises, employers may choose to wait and see before filling new positions, contributing to higher unemployment. At the same time, heightened uncertainty also reduces consumer spending because households choose to increase saving for precautionary reasons, for example, in case they lose their jobs. The decline in consumer spending reduces aggregate demand, further raising unemployment in addition to pushing inflation down.

In theory, heightened uncertainty can raise unemployment because a job match represents a long-term employment relationship and hiring decisions are costly to reverse. When uncertainty rises, employers may choose to wait and see before filling new positions, contributing to higher unemployment. At the same time, heightened uncertainty also reduces consumer spending because households choose to increase saving for precautionary reasons, for example, in case they lose their jobs. The decline in consumer spending reduces aggregate demand, further raising unemployment in addition to pushing inflation down.

These theoretical predictions are supported by empirical evidence. Figure 2 traces out the average statistical effects of an uncertainty shock on the three macroeconomic variables in the model. Each panel shows the average as a solid line, with shading indicating a 90% certainty that the average falls within that area. Following a sudden rise in uncertainty, the unemployment rate shown in panel A rises over time, reaching a peak effect roughly one year after the impact. Similarly, panel B shows that the inflation rate falls persistently for about six months before starting to rise again. The interest rate falls quickly, reflecting monetary policy easing in response to the uncertainty shock.

The combination of a rise in the unemployment rate – that is, a decline of economic activity – and a fall in inflation suggests that uncertainty affects the economy in a way similar to a reduction in aggregate demand (Leduc and Liu 2016). Thus, through uncertainty, the COVID-19 pandemic has important demand-side effects in addition to the supply-side effects such as supply chain disruptions and labor shortages.

The combination of a rise in the unemployment rate – that is, a decline of economic activity – and a fall in inflation suggests that uncertainty affects the economy in a way similar to a reduction in aggregate demand (Leduc and Liu 2016). Thus, through uncertainty, the COVID-19 pandemic has important demand-side effects in addition to the supply-side effects such as supply chain disruptions and labor shortages.

Policy responses to supply-side effects often involve a tradeoff because supply disruptions typically push up both unemployment and inflation. If the Fed reduced interest rates to offset the rise in unemployment, it would risk further increases in inflation. Alternatively, if the Fed raised interest rates to stabilize inflation, it would risk amplifying the rise in unemployment.

In contrast, monetary policy can more easily offset the impact of a decline in aggregate demand, since cutting interest rates helps reduce unemployment and simultaneously raises inflation. Thus, demand shocks do not introduce difficult tradeoffs between the Federal Reserve’s maximum employment and price stability objectives. The decline in the interest rate following an increase in uncertainty reflects the fact that the Federal Reserve has historically attempted to offset the demand-like impact of uncertainty by cutting short-term interest rates.

Using our estimated model, we can assess the likely magnitude and duration of the macroeconomic effects of the current uncertainty spikes associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. In particular, an uncertainty shock that boosts the VIX to a level comparable to that observed in the past few weeks raises the unemployment rate by about 1 percentage point in roughly 12 months. The same uncertainty shock would reduce the inflation rate by about 2 percentage points in about six months. In turn, monetary policymakers would be expected to rapidly bring the policy rate down to the effective lower bound, as was indeed the case when the Federal Reserve cut its federal funds rate in March.

Conclusion

In addition to the tragic human toll, the COVID-19 pandemic will severely reduce economic activity as nonessential retail and other business activity is curtailed and social distancing policies and quarantines force people to stay home. The negative impact on the economy can be further amplified and prolonged by rising uncertainty. Our estimates suggest that the spikes in uncertainty triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic will contribute to a protracted increase in unemployment and a significant decline in the inflation rate in the United States. The Fed’s decision in March to cut the federal funds rate to a near-zero level can partly cushion these demand-like effects resulting from the more uncertain environment.

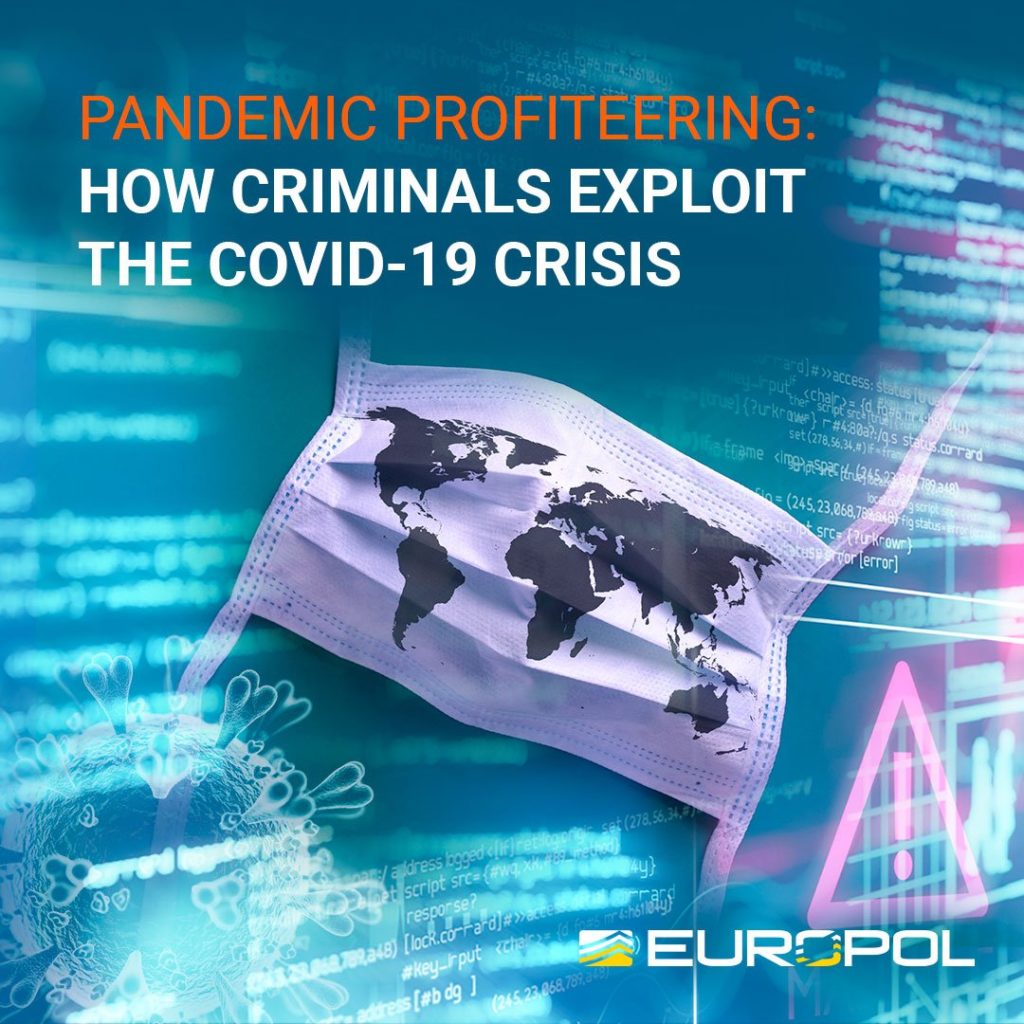

Criminals Profit From The COVID-19 Pandemic

During this unprecedented crisis, governments across Europe are intensifying their efforts to combat the global spread of the coronavirus by enacting various measures to support public health systems, safeguard the economy and to ensure public order and safety.

A number of these measures have a significant impact on the serious and organised crime landscape. Criminals have been quick to seize opportunities to exploit the crisis by adapting their modi operandi or engaging in new criminal activities. Factors that prompt changes in crime and terrorism include:

- High demand for certain goods, protective gear and pharmaceutical products;

- Decreased mobility and flow of people across and into the EU;

- Citizens remain at home and are increasingly teleworking, relying on digital solutions;

- Limitations to public life will make some criminal activities less visible and displace them to home or online settings;

- Increased anxiety and fear that may create vulnerability to exploitation;

- Decreased supply of certain illicit goods in the EU.

Building upon information provided by EU Member States and in-house expertise, Europol has published today a situational report analysing the current developments which fall into four main crime areas:

CYBERCRIME

The number of cyberattacks against organisations and individuals is significant and is expected to increase. Criminals have used the COVID-19 crisis to carry out social engineering attacks themed around the pandemic to distribute various malware packages.

Cybercriminals are also likely to seek to exploit an increasing number of attack vectors as a greater number of employers institute telework and allow connections to their organisations’ systems.

Example: The Czech Republic reported a cyberattack on Brno University Hospital which forced the hospital to shut down its entire IT network, postpone urgent surgical interventions and re-route new acute patients to a nearby hospital.

FRAUD

Fraudsters have been very quick to adapt well-known fraud schemes to capitalise on the anxieties and fears of victims throughout the crisis. These include various types of adapted versions of telephone fraud schemes, supply scams and decontamination scams. A large number of new or adapted fraud schemes can be expected to emerge over the coming weeks are fraudsters will attempt to capitalise further on the anxieties of people across Europe.

Example: An investigation supported by Europol focuses on the transfer of €6.6 million by a company to a company in Singapore in order to purchase alcohol gels and FFP3/2 masks. The goods were never received.

COUNTERFEIT AND SUBSTANDARD GOODS

The sale of counterfeit healthcare and sanitary products as well as personal protective equipment and counterfeit pharmaceutical products has increased manifold since the outbreak of the crisis. There is a risk that counterfeiters will use shortages in the supply of some goods to increasingly provide counterfeit alternatives both on- and offline.

Example: Between 3-10 March 2020, over 34 000 counterfeit surgical masks were seized by law enforcement authorities worldwide as part of Operation PANGEA supported by Europol.

ORGANISED PROPERTY CRIME

Various types of schemes involving thefts \have been adapted by criminals to exploit the current situation. This includes the well-known scams involving the impersonation of representatives of public authorities. Commercial premises and medical facilities are expected to be increasingly targeted for organised burglaries.

Despite the introduction of further quarantine measures throughout Europe, the crime threat remains dynamic and new or adapted types of criminal activities will continue to emerge during the crisis and in its aftermath.

Example: Multiple EU Member States have reported on a similar modus operandi for theft. The perpetrators gain access to private homes by impersonating medical staff providing information material or hygiene products or conducting a “Corona test”.

Executive Director Catherine De Bolle said: “While many people are committed to fighting this crisis and helping victims, there are also criminals who have been quick to seize the opportunities to exploit the crisis. This is unacceptable: such criminal activities during a public health crisis are particularly threatening and can carry real risks to human lives. That is why it is relevant more than ever to reinforce the fight against crime. Europol and its law enforcement partners are working closely together to ensure the health and safety of all citizens”.

European Commissioner for Home Affairs Ylva Johansson said: “I welcome this new Europol report on latest developments of COVID-19 on the criminal landscape in the EU. The EU and Member States are stepping up efforts to keep people safe: National authorities and EU Agencies like Europol and ENISA are providing valuable input into how we can tackle this challenge together. I am determined to ensure that the Commission does all in its power to support law enforcement in the face of this new threat.”

Pandemic Profiteering How Criminals Exploit The Covid 19 Crisis

@Europol

Europol

Targeting Aid in Crisis

The imagery floats in sepia-colored photographs, faintly recalled images of bedraggled people lined up for bread or soup, write March Gordon of ABC News. Shacks in Appalachian hollows. Ruined investors taking their lives in the face of stock market crashes. Desperation etched on the faces of a generation that would soon face a world war.

By now, it’s hard to find someone whose grandparents are old enough to recall the suffering of the Great Depression or the stream of rescue programs the government unleashed in response to it. All but gone, too, are memories of President Franklin Roosevelt’s “fireside chats,” his attempts to console an anxious populace and quell the “fake news” rumors of the day.

Nearly a century later, the U.S. economy is all but shut down, and layoffs are soaring at small businesses and major industries. A devastating global recession looks inevitable. Deepening the threat, a global oil price war has erupted. Some economists foresee an economic downturn to rival the Depression.

“With the markets destroying wealth so quickly, the two shocks we’re seeing globally – the coronavirus and the oil-price war – could morph into a financial crisis,” said Carmen Reinhart, a professor of economics and finance at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government. “We will see higher default rates and business failures. It could be like the 1930s.”

During the early Depression years, unemployment peaked at 25%. U.S. economic output plunged nearly 30%. Thousands of banks failed. Millions of homeowners faced foreclosure. Businesses failed.

No one knows how this recession may unfold or how effectively the government’s rescue programs might help. Ignited by an external event – a raging global pandemic – it is uniquely different from both the Depression and the financial meltdown of 2008-09. And so its possible solutions are trickier.

It isn’t a conventional dislocation rooted in a financial collapse or an overheated economy or a burst asset bubble. The twist this time is that the only sure way to defeat the pandemic – with drastic containment measures like lockdowns, quarantines and business closures – is to deliberately cause a recession by bringing business and social life to a halt.

James Bullard, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, has gone so far as to warn that unemployment could reach 30% within months and that economic output could shrink 50%. Other outlooks aren’t quite as grim. But they’re all bleak.

Some economists take heart from the fact that the government possesses more potent tools to stabilize the economy than it did in the 1930s, some of them created in response to the Depression. They include a social safety net in unemployment insurance, a guarantee of bank deposits and federally backed mortgages. And the 2008 financial crisis led to the creation of an array of programs to fortify the banking system and encourage borrowing and spending.

President Donald Trump, after a hesitant start, now backs a bold and multi-pronged federal response to the crisis. It is just the sort of sweeping government involvement in the economy that was pushed this year by Democratic presidential candidates, well before the viral outbreak, but is almost always resisted by Trump and other Republicans.

After days of negotiations between congressional leaders and White House officials, Congress edged toward an agreement Tuesday on legislation that would deliver, by far, the largest economic rescue plan in U.S. history. At somewhere around $2 trillion, the wide-ranging aid package is intended to sustain workers and companies for at least 10 weeks. After that, further help might be needed.

The final package is expected to include, among other things, one-time cash payments of $1,200 to individuals and $3,000 for a family of four; more generous unemployment benefits for workers sidelined by the virus; an extension of that coverage to gig workers and independent contractors; and small business loans to help retain workers. An earlier $100 billion-plus package passed by Congress last Wednesday and signed by Trump includes a guarantee of paid sick leave for some workers affected by the virus.

A major element of the government’s intervention will continue to be the Federal Reserve, which is injecting trillions of dollars in liquidity into the financial system to support key lending programs. On Monday, the Fed unleashed its boldest effort yet to protect the U.S. economy by helping companies and governments pay their bills. With lending markets threatening to shut down, the Fed’s intervention is intended to ensure that households, companies, banks and governments can get the loans they need at a time when their own revenue is drying up.

As a whole, the emerging all-guns-blazing federal response is at least an echo of the economic stimulus that Roosevelt engineered in the depths of the Depression. Huge government aid programs put tens of millions to work in the construction of public buildings and roads, the pursuit of conservation projects and development of the arts.

Rural poverty was addressed, in part, by buying low-producing land owned by poor farmers and resettling them in group farms. Fannie Mae was created to buy home mortgages issued by the Federal Housing Administration. After the immediate crisis passed, Congress enacted far-reaching reforms of the financial system and banks and established unemployment insurance.

In contrast to today, the 1930s workforce was predominantly a male-dominated one of manual and farm labor. That changed only later, when the “Rosie the Riveter” wave of women entered factories to help mobilize America to fight World War II – a mobilization whose economic boost finally ended the Depression.

Today’s service sector-dominated 21st century economy, populated more by retail, technology and financial services as well as by contractors, freelancers and “gig” workers, is far different. A 2020 equivalent of the Works Progress Administration would be hard to imagine.

In today’s environment, more likely than government-created jobs are temporary measures like cash payments and guaranteed paid sick leave. Yet the options for the government are so vast that experts say they could deliver a significant benefit if deployed properly.

“There are more levers now for the government,” says Richard Grossman, who teaches economic and financial history at Wesleyan University. “There’s a lot now that the government can do that it wouldn’t even have thought of doing in the 1930s.”

An example was a rarely used 1950s-era lever that Trump invoked last week – the Defense Production Act. It empowers the government to marshal private industry to accelerate production of key supplies in the name of national security. (Critics complain that Trump has yet to put the law fully into action by actually ordering companies to make protective masks and other equipment that hospitals say are running dangerously low.)

Also last week, the president said he was open to giving the government a vast reach into the private sector – by taking equity stakes in companies that have been crippled by the virus, in exchange for giving the companies emergency loans.

This would recall the 2008-09 financial crisis, when the government engineered a $700 billion bailout of banks and automakers – and, in exchange, acquired equity stakes in those companies. That enabled the government to profit years later, when the companies repaid the taxpayer bailouts. The government took over outright the home mortgage backers Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

“Right now, the country’s frozen,” said Anat Admati, a professor of finance and economics at Stanford University and senior fellow at Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research. “Policymakers have to decide what’s really best for society.”

Admati notes that FDR’s New Deal and unemployment insurance wove a new safety net after the ravages of the Depression. But the net has eroded over the last decade, she says, along with the rise in gig and part-time workers and low-paid staffers in health care and other service industries. Many of those workers don’t stand to benefit much, if at all, from unemployment benefits and other programs built for a different era.

A result is that income inequality could worsen as a result of the crisis and the economic and social dislocation it causes.

“There are bailouts and subsidies coming,” Admati said. “The key is how they are targeted.”

–

Paying Salaries versus Unemployment Benefits During Health Crisis

More than three million Americans filed for unemployment benefits last week, a total far higher than in any previous week in the modern history of the United States, has been greeted with surprising equanimity by the nation’s political leaders, say the New York Ties editorial board.

More than three million Americans filed for unemployment benefits last week, a total far higher than in any previous week in the modern history of the United States, has been greeted with surprising equanimity by the nation’s political leaders, say the New York Ties editorial board.

They appear to regard mass unemployment as an unfortunate but unavoidable symptom of the coronavirus. “It’s nobody’s fault, certainly not in this country,” President Trump said Thursday. The federal government’s primary response is a bill that passed the US Senate. that passed the US Senate. The bill would provide larger cash payments to those who have lost their jobs.But the sudden collapse of employment was not inevitable. It is instead a disastrous failure of public policy that has caused immediate harm to the lives of millions of Americans, and that is likely to leave a lasting mark on their future, on the economy and on our society.

The pain will be felt most acutely in the least affluent parts of the nation, struggling even before the coronavirus crisis and even after a decade of steady though unequal economic growth.

The federal government’s first and best chance to prevent mass unemployment was to keep the new coronavirus under control through a system of testing and targeted quarantines like those implemented by a number of Asian nations. But even after it became clear that the Trump administration had failed to prepare for the pandemic, policymakers still could have chosen to prioritize employment by paying companies to keep workers on the job during the period of lockdown.

A number of European countries, after similarly failing to control the spread of the virus, and thus being forced to lock down large parts of their economies, have chosen to protect jobs. Denmark has agreed to compensate Danish employers up to 90 percent of their workers’ salaries. In the Netherlands, companies facing a loss of at least 20 percent of their revenue can similarly apply for the government to cover 90 percent of payroll. And the United Kingdom announced that it would pay up to 80 percent of the wage bill for as many companies as needed the help, with no cap on the total amount of public spending.

Some countries only pay employers for workers who aren’t working. Under Germany’s Kurzarbeit scheme, the government chips in even for workers kept on part time. The German government predicts that 2.35 million workers will draw benefits during the crisis. In either case, the goal is to preserve people in existing jobs — to preserve the antediluvian fabric of the economy to the greatest extent possible, for the benefit of workers and firms.

“What we’re trying to do is to freeze the economy,” the Danish employment minister, Peter Hummelgaard, “It’s about preserving Main Street as much as we can.”

Preserving jobs is important because a job isn’t merely about the money. Compensated labor provides a sense of independence, identity and purpose; an unemployment check does not replace any of those things. People who lose jobs also lose their benefits — and in the United States, that includes their health insurance. And a substantial body of research on earlier economic downturns documents that people who lose jobs, even if they eventually find new ones, suffer lasting damage to their earnings potential, health and even the prospects of their children. The longer it takes to find a new job, the deeper the damage tends to be.

American companies have long fought to maximize their freedom to shed workers during economic downturns, and American economists have tended to agree, arguing that easy separation facilitates adjustments in the allocation of resources, allowing weaker businesses to shrink and stronger businesses to grow.

The American economy has outpaced Europe, and the freedom to fire workers may well be a factor. But the benefits have accrued primarily to shareholders. The European model has been better for workers, who have experienced faster income growth than in the United States.

And this downturn is not an example of the kind of periodic free-market “creative destruction” that those who embrace this theory tend to celebrate — it’s a public-health crisis. The nation has taken ill, and it needs to go to bed for a while. But there’s no obvious reason to think the economy would benefit from the kinds of big economic shifts facilitated by mass unemployment. This economic contraction was not caused by too much housing construction or too much gambling on Wall Street. It was caused by the arrival of a virus, and preserving ties between companies and workers could help to accelerate the eventual economic recovery once the pandemic passes. Companies could keep trained and experienced employees, averting the need for people to look for jobs and for companies to look for workers.

The United States has made some efforts to preserve jobs, particularly at small businesses. The bailout bill includes $367 billion for loans to small businesses that would be forgiven if recipients avoid job and wage cuts.

And the bill does not require big companies that get bailouts to make similar efforts.

Instead, the government agreed to give workers who lose their jobs an extra $600 a week.

We’d all be better off if the government had helped those workers keep their jobs instead.