Cutting off the financing for ISIS is critical. Mark Gilbert writes: Dr. Christina Schori Liang, a senior fellow at the Geneva Centre for Security Policy, notes in a paper for the IEP that IS (also known as ISIL or ISIS) is “the richest terrorist organization in history, with an estimated wealth of $2 billion.” IS earns about $1.5 million a day from selling oil, producing as many as 40,000 barrels per day and selling for as little as $20 a barrel. The oil is smuggled through Iraq and Kurdistan, border guards are bribed, while donkeys and trucks traverse deserts and mountain passes to avoid detection. IS has its own underground pipelines and refineries; while coalition forces had destroyed 16 mobile refineries by the end of last year, they can be rebuilt for as little as $230,000.

Its income is boosted by trafficking people and auctioning slaves, kidnapping for ransom (raising $45 million last year), extortion, taxes on income, business revenues and consumer goods in the lands it controls, as well as looting and selling antiquities. The Financial Action Task Force reckons IS stole about $500 million late last year just by raiding state-owned banks in the territories it controls. As Liang argues, “the West has so far failed to impede ISIL’s financial gains which are marked by a fluidity and wealth never seen before.”

Strangling the flow of cash that allows IS to arm its jihadists and fund the local infrastructure in the regions it occupies could smother the organization in ways that may prove even more effective than bombing its bases. As the journal Studies in Conflict and Terrorism noted as long ago as 2004 in a report on al-Qaeda, though, terrorist groups typically rely on informal money transfer networks and under-regulated Islamic finance channels which are harder to close down.

Thomas Sanderson, co-director of the Transnational Threats Project at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, said:

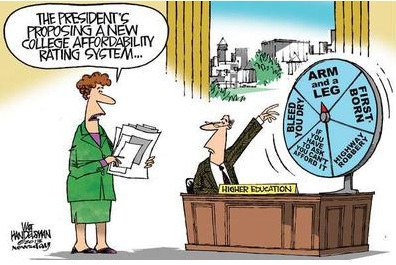

Our options and appetite for more investment of blood and treasure in the fight against terrorism may be limited, but without addressing all dimensions of the financing threat, our progress over the years may be lost. If groups like ISIS can fill their coffers, run economies and consolidate their hold on power, we may be facing a new, more dangerous brand of global terrorism that will threaten the United States and its allies for years to come.

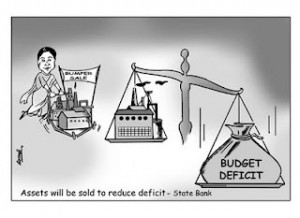

Driving a wedge between IS and the dollars it needs demands greater cooperation between the various countries that profess to oppose the group, more punishing sanctions against any nation found to have turned a blind eye to stolen oil crossing its borders, a coordinated refusal to pay ransoms, and severe retributions against anyone found to participate in the trading of looted treasure. Waging financial war on IS to undermine its ability to operate as a nation state should clearly be more of a priority than it has been so far.