Innovative Office Space. No more corner office. The survival of the fittest is gone. Here are four ideas of how work can best be done.

Category Archives: Finance

Clinton Tiptoes Around Taxation in the US

Naomi Jagoda writes: Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton called for an additional 4 percent tax on people making more than $5 million per year. Clinton called the tax a “fair share surcharge” that would make sure wealthier taxpayers pay higher tax rates.

“This surcharge is a direct way to ensure that effective rates rise for taxpayers who are avoiding paying their fair share, and that the richest Americans pay an effective rate higher than middle-class families,” a Clinton campaign aide said.

The surcharge would raise more than $150 billion over 10 years. It is part of Clinton’s plan to build on the principle of the “Buffett Rule” to raise the effective tax rates of the rich.

The Buffett Rule, named after philanthropist billionaire Warren Buffett, would ensure that those making more than $1 million pay at least 30 percent of their incomes in taxes.

Clinton intends to release more proposals that would increase the amount of taxes paid by the wealthy later this week, the aide said.

The former secretary of State also plans to release more proposals that would provide tax relief to the middle class. She has already proposed tax credits for excessive healthcare costs and for family members caring for ailing parents and grandparents.

The campaign of Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.), Clinton’s main rival for the Democratic presidential nomination, criticized the proposal. as “too little too late.”

Without defining surcharge, and without suggesting a fair tax overhaul, Clinton’s proposal may be meaningless. Let the dialogue begin, for instance, on whether the first $50,000 of every American’s income go free of tax. Donald Trump has suggested this.

Economics, the Environment and Foreign Policy Conspire to End Oil?

Alexander Bolton writes: As the price of oil plunges to its lowest point in 12 years — and threatens to drag the broader U.S. economy down with it — lawmakers say Congress should consider helping teetering energy companies with policy fixes beyond the decision to lift the oil-export ban.

Among the proposals under discussion: Expediting the process for exporting liquefied natural gas, and upgrading infrastructure to move energy to market more quickly and cheaply.

Another top priority is loosening environmental and other regulations. But moves in that direction are highly unlikely while a Democrat remains in the White House.

With oil currently below $33 a barrel, some on Capitol Hill are calling for quick action.

Some lawmakers are floating the possibility of taking retaliatory trade measures against Saudi Arabia, which has flooded the market with cheap oil in what some analysts see as a bid to drive America’s growing shale oil industry out of business.

The House version of the energy legislation includes language to expedite natural gas exports.

The Obama administration has proposed nearly 100 regulations for the oil and gas industry, ranging from restrictions on methane and carbon dioxide to limits on operating on federal land.

Legislation passed last month to lift the four-decade ban on oil exports is expected to boost exports by 500,000 barrels a day but so far it has had little impact on prices.

Goldman Sachs has warned that oil may sink as low as $20 a barrel, which would shake financial markets by sinking energy stocks, driving companies into bankruptcies and setting off a round of junk-bond defaults.

Third Avenue Investment, a New York-based fund, last month blocked clients from pulling their money, prompting a sell-off of high-yield bonds and evoking memories of the 2008 meltdown.

Growing tensions between Saudi Arabia and Iran over the execution of a Shiite cleric might have been thought to have boosted prices by raising the specter of regional conflict. But that had little effect on oil prices this past week.

Bankruptcies among oil and gas companies have hit the highest quarterly level since the midst of the 2008 financial crisis, Bloomberg Business reported last month.

Oil and gas companies have laid off more than 250,000 workers and that number could swell in the months ahead.

Saudi Arabia, taking advantage of its low extraction costs, has refused to curb oil production in a bid to expand market share and undercut competitors. This has raised the prospect of the U.S. government taking action to level the playing field for domestic companies.

If the energy industry continues to sink, other proposals will pop up in the energy negotiations due to kick off next week. There are calls for new infrastructure: the right mix of pipelines, transmission lines, rail, roads,” he said.

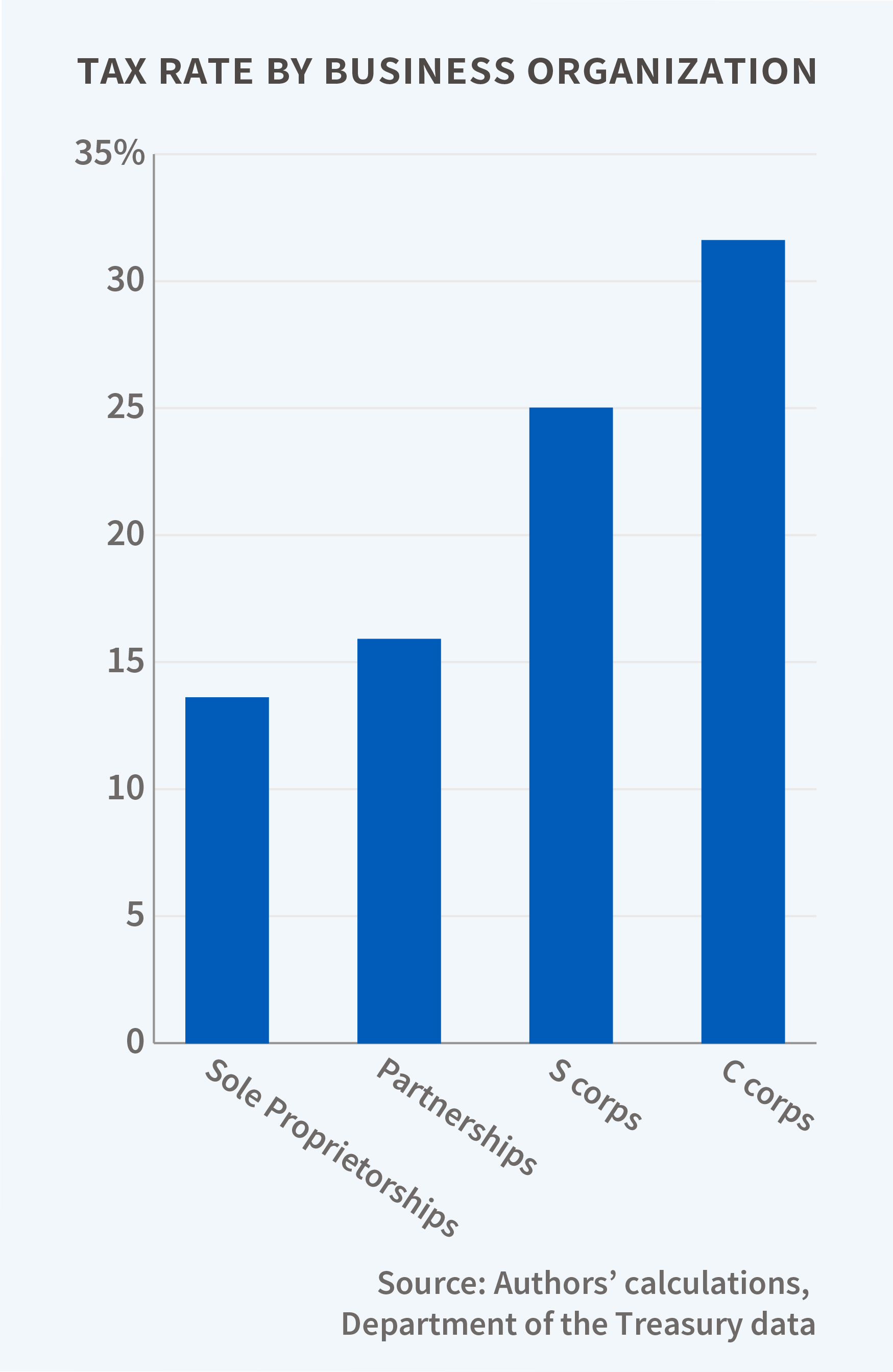

Why the Tax Code Needs Reform in the US

Pass through businesses increase in US.

he importance of pass-through business entities has soared in the past three decades. Over the same period, the amount of pass-through business income flowing to the top 1 percent of income earners has increased sharply. Despite this profound change in the organization of U.S. business activity, we lack clean, clear facts about the consequences of this change for the distribution and taxation of business income.

Pass-through entities — partnerships, tax code subchapter S corporations, and sole proprietorships — are not subject to corporate income tax. Their income passes directly to their owners and is taxed under whatever tax rules those owners face. In contrast, the income of traditional corporations, more specifically subchapter C corporations, is subject to corporate income taxes, and after-tax income distributed from the corporation to its owners is also taxable.

In 1980, pass-through entities accounted for 20.7 percent of U.S. business income; by 2011, they represented 54.2 percent. Many partnerships are opaque. A fifth of partnership income was earned by partners that the study’s authors were not able to classify into one of several categories, such as a domestic individual or a foreign corporation. In addition, some partnerships are circular, in the sense that they are owned by other partnerships, which could in turn be owned by yet other partnerships.

Pass-through business income faces lower tax rates than traditional corporate income. The tax rate on the income earned by pass-through partnerships is a relatively low 15.9 percent, excluding interest payments and unrepatriated foreign income. That compares with a 31.6 percent rate for C corporations and a 24.9 percent rate for S corporations. Only sole proprietorships have a lower average rate, 13.6 percent. Combining both taxes on corporations and taxes on investors, the researchers calculate that the U.S. business sector as a whole pays an average tax rate of 24.3 percent.

The lower average tax rate for pass-through entities than for traditional corporations translates into reduced federal revenues, the researchers conclude. They estimate that in 2011, if the share of pass-through tax returns had been at its 1980 level, when traditional C corporations and sole proprietorships dominated, the average rate would have been 3.8 percentage points higher and the Treasury would have collected $100 billion more in tax revenue.

One reason partnerships pay such a low average tax rate is that nearly half their income (45 percent) is classified as capital gains and dividend income, which is taxed at preferential rates. Another 15 percent of their income is earned by tax-exempt and foreign entities, for which the effective tax rate is less than five percent. The roughly 30 percent of partnership income that is earned by unidentifiable and circular partnerships is taxed at an estimated 14.7 percent rate.

US Fed: Maintain Full Employment?

J.W. Mason writes: To the surprise of no one, the Federal Reserve recently raised the federal funds rate — the interest rate under its direct control — from 0–0.25 percent to 0.25–0.5 percent, ending seven years of a federal funds rate of zero.

But while widely anticipated, the decision still clashes with the Fed’s supposed mandate to maintain full employment and price stability. Inflation remains well shy of the Fed’s 2 percent benchmark (its interpretation of its legal mandate to promote “price stability”) — 1.4 percent in 2015, according to the Fed’s preferred personal consumption expenditure measure, and a mere 0.4 percent using the consumer price index — and shows no sign of rising.

US GDP remains roughly 10 percent below the pre-2008 trend, so it’s hard to argue that the economy is approaching any kind of supply constraints. And setting aside the incoherent notion of “price stability” (let alone of a single metric to measure it), according to the Fed’s professed rulebook, the case for a rate increase is no stronger today than a year or two ago.

While the consensus view considers the main job of central banks to be maintaining price stability by adjusting the short-term interest rate, this has never been the whole story.

The conscious planning that confines market outcomes within tolerable bounds is hidden from view because if the role of planning was acknowledged, it would undermine the idea of markets as natural and spontaneous and demonstrate the possibility of conscious planning toward other ends.

The Fed is a central planner. One particular problem for central bank planners is managing the pace of growth for the system as a whole. Fast growth doesn’t just lead to rising prices — left to their own devices, individual capitalists are liable to bid up the price of labor and drain the reserve army of the unemployed during boom times. Making concessions to workers when demand is strong is rational for individual business owners, but undermines their position as a class.

Modern central bankers pay close attention to the somewhat misleadingly labeled labor market, and use low unemployment as a signal to raise interest rates.

So in this respect it isn’t surprising to see the Fed raising rates, given that unemployment rates have now fallen below 5 percent for the first time since the financial crisis.

Indeed, inflation targeting has always been coupled with a strong commitment to restraining the claims of workers. Paul Volcker is now widely admired as the hero who slew the inflation dragon, but as Fed chair in the 1980s, he considered rolling back the power of organized labor — in terms of both working conditions and wages — to be his number one problem.

Volcker’s successors at the Fed approached the inflation problem similarly. Alan Greenspan saw the fight against rising prices as, at its essence, a project of promoting weakness and insecurity among workers.

Testifying before Congress in 1997, Greenspan attributed the “extraordinary’” and “exceptional” performance of the nineties economy to “a heightened sense of job insecurity” among workers “and, as a consequence, subdued wages.”

As Greenspan’s colleague at the Fed in the 1990s, Janet Yellen took the same view.

And when a few high-profile union victories, like the Teamsters’ successful 1997 strike at UPS, seemed to indicate organized labor might be reviving, Greenspan made no effort to hide his displeasure.

While it might look like naked class warfare to deliberately raise unemployment to keep wage demands “subdued” (in the soothing language of the Fed’s public statements), the Fed assures us that it’s really in the best interests of everyone, including workers.

Parking Money

Cass R. Sunstein writes: In some circles, “redistribution” of wealth has become a dirty word, and recent efforts to make the tax system more progressive have run into serious political resistance, above all from Republicans. But whatever your political party, you are unlikely to approve of the illegal use of tax havens. As it turns out, a lot of wealthy people in the United States, Europe, and elsewhere have been hiding money in foreign countries—above all, Switzerland, Luxembourg, and the Virgin Islands. As a result, they have been able to avoid paying taxes in their home countries. Until recently, however, officials have not known the magnitude of that problem.

But people are paying increasing attention to it. A vivid new documentary, The Price We Pay, connects tax havens, inequality, and insufficient regulation of financial transactions. The film makes a provocative argument that a new economic elite—wealthy managers and holders of capital—is now able to operate on a global scale, outside the constraints of any legal framework. In a particularly chilling moment, it shows one of the beneficiaries of the system cheerfully announcing on camera: “I don’t feel any remorse about not paying taxes. I think it’s a marvelous way in life.”

Gabriel Zucman, who teaches at the University of California at Berkeley, has two goals in his new book, The Hidden Wealth of Nations: to specify the costs of tax havens, and to figure out how to reduce those costs. While much of his analysis is technical, he writes with moral passion, even outrage; he sees tax havens as a “scourge.” His figures are arresting. About 8 percent of the world’s wealth, or $7.6 trillion, is held in tax havens. In 2015, Switzerland alone held $2.3 trillion in foreign wealth. As a result of fraud from unreported foreign accounts, governments around the world lose about $200 billion in tax revenue each year. Most of this amount comes from the evasion of taxes on investment income, but a significant chunk comes from fraud on inheritances. In the United States, the annual tax loss is $35 billion; in Europe, it is $78 billion. In African nations, it is $14 billion. Parking Money

Set-in-their-ways Economists Hurt Economies?

Federico Fubini wries: RePEc (Research Papers in Economics) arguably provides the closest thing to a credible hierarchy of economists, not unlike the ATP’s rankings of professional tennis players. The site, entirely open and free maintains a decentralized online database of around two million items of economic research, including working papers, journal articles, books, and software. Its index of influence assesses the number of citations for each author, weighted by impact and discounted by citation age (otherwise, Adam Smith and Karl Marx would likely still top the list).

Because the ranking is updated every month, RePEc enables one to track which economists are viewed by their peers as the most influential over time. So I compared the rankings from December 2006 and September 2015 to see whether the RePEc index had evolved along with economic reality.

It had not. Despite the profound – and largely unpredicted – financial and economic turmoil of the intervening decade, the intellectual influence of those whose theories suffered the most evidently remains undented.

After a succession of bursting multi-trillion-dollar credit bubbles, you might wonder what to make of Robert Lucas’s view that rational expectations enable perfectly calculating “agents” to maximize economic utility. You might also want to rethink Eugene Fama’s efficient markets hypothesis, according to which prices of financial assets always reflect all available information about economic fundamentals.

You must not be an economist. In fact, Lucas and Fama both moved up in the RePEc rankings during the period I examined, from 30 to nine and from 23 to 17, respectively. And the persistence at the top is striking across the board. Among the top ten economists in September 2015, six were already there in December 2006, and another two were ranked 11 and 13.

What is remarkable about this is the difference between the pace of change in the ranking of economists and in the economy itself. Entry barriers among the world’s ten richest people and ten most valuable companies seem to be far lower than among the top ten economists. According to Forbes, only two of the ten wealthiest individuals in 2015 (Bill Gates and Warren Buffett) were in the top ten in 2006. And just three companies – ExxonMobil, General Electric, and Microsoft – made the top ten in terms of market capitalization in both 2006 and 2015.

In the rankings of economists, by contrast, criteria such as gender or geographic origin confirm the overall inertia. Only four women made the RePEc top 200 in September 2015, compared to three in December 2006, and two were included on both lists.

The rest of the RePEC top 200 tend to be Caucasian men in their 60s and older – roughly three decades past the age when an economic or scientific author is generally most innovative, according to research by the economist Benjamin Jones. No black person, American or otherwise, is in the top 200.

How surprised should we be that, even after the Great Recession cast grave doubt on the rational-market theories so dominant a decade ago, the top tier of academic economics remains largely unchanged?

Might the world’s leading economists be so keen to protect their own ideas that they ignore (or, worse, stifle) innovation from unexpected quarters?

For a group of people so committed to free markets and so enamored of “creative destruction,” that is a question that urgently needs to be addressed. The answer may hold enormous implications not only for intellectual growth, but also for human welfare.

Lagarde Cautions: Manage Currencies!

Christine Lagarde writes: November’s terrorist attack in Paris and the influx of refugees into Europe are but the latest symptom of sharp political and economic tensions in North Africa and the Middle East. And these events are by no means isolated. Conflicts are raging elsewhere, too, and there are close to 60 million displaced people worldwide.

Moreover, 2015 was expected to be one of the hottest years on record, with an extremely strong El Niño that has spawned weather-related calamities across the Pacific. And the arrival of interest-rate normalization in the United States, together with China’s slowdown, is contributing to uncertainty and higher economic volatility worldwide. Indeed, there has been a sharp deceleration in the growth of global trade, with the drop in commodity prices posing problems for resource-based economies.

One reason that the global economy is so sluggish is that, seven years after the collapse of Lehman Brothers, financial stability is not yet assured. Financial-sector weaknesses linger in many countries – and financial risks are growing in emerging markets.

Putting all of this together, global growth in 2016 will be disappointing and uneven. The global economy’s medium-term growth prospects have weakened as well, because potential growth is being held back by low productivity, aging populations, and the legacies of the global financial crisis. High debt, low investment, and weak banks continue to burden some advanced economies, especially in Europe; and many emerging economies continue to face adjustments after their post-crisis credit and investment boom.

This outlook is heavily affected by some major economic transitions that are creating global spillovers and spillbacks, particularly China’s transition to a new growth model and the normalization of US monetary policy. Both shifts are necessary and healthy. They are good for China, good for the US, and good for the world. The challenge is to manage them as efficiently and as smoothly as possible. Lagarde Assesses the State of the World

China’s Emergence Plagues the West

joseph E.Stiglitz writes: Last year was a memorable one for the global economy. Not only was overall performance disappointing, but profound changes – both for better and for worse – occurred in the global economic system.

On the positive side are the Paris climate agreement and the impending end of fossil fuels as the mina source of energy. Trade is more complicated as is China’s continued growth in power and population. Nobelist Joseph E. Steiglitz on the state of the globe

What Happens When One Currency Bifurcates?

Yanis Yaroufakis wriets: Imagine a depositor in the US state of Arizona being permitted to withdraw only small amounts of cash weekly and facing restrictions on how much money he or she could wire to a bank account in California. Such capital controls, if they ever came about, would spell the end of the dollar as a single currency, because such constraints are utterly incompatible with a monetary union.

The reality of Greece’s two currencies is the most vivid demonstration yet of the fragmentation of Europe’s monetary “union.” In comparison, Arizona has never looked so good. Bifurcating Currencies