David Cameron has defended the deal UK authorities have struck with Google over tax, saying the Conservatives have done more than any other government.

The PM told the Commons the tax “should have been collected under [the last] Labour government”.

Google agreed to pay £130m back in tax to HM Revenue and Customs – which said that was the “full tax due in law”.

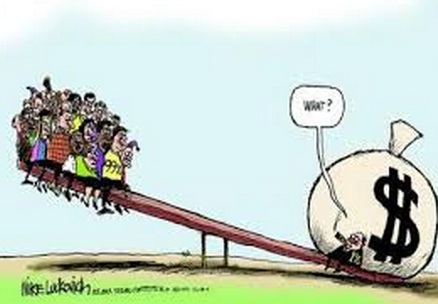

But European MPs have described it as a “very bad deal”, and Labour said it amounted to a 3% tax rate.

The vice-chairwoman of a European tax committee said the deal showed the UK was preparing “to become a kind of tax haven to attract multinationals”.

French MEP Eva Joly said the settlement was “bad news for everybody”.

She said it was difficult to know on what basis the figure was reached and she criticised the attempt to “make publicity out of it” by talking about large-sounding figures which she said were a fraction of what should be paid.

Ms Joly, who is vice-chairwoman of the Special European Parliamentary Committee on Tax Rulings, said: “We will ask him [Mr Osborne] to come and explain and I hope he will.”

Mr Osborne has already faced criticism from some politicians in the UK over the tax deal. Shadow chancellor John McDonnell has written to him demanding details of how the settlement was reached.

And Conservative MP Mark Garnier, a member of the Treasury select committee, said the agreement represented a “relatively small” amount of money compared with Google’s UK profits.

Reports in Wednesday’s Times newspaper say Italy is poised to strike a far tougher tax deal with Google than the UK’s. It refers to stories in Italian media that suggest Google will pay £113m in back taxes to the Italian government, equating to a 15% tax rate.

The deal has not yet been completed so it is not known how many years it covers.

The Italian finance minister can also expect a call to appear before the MEPs, Ms Joly said.

Google is one of several multinational companies to have been accused of avoiding tax, in spite of making billions of pounds of sales in Britain.

Senior figures at the company said it would follow new rules which would see it pay more taxes in future.

Head of Google Europe Matt Brittin said last week: “We were applying the rules as they were and that was then and now we are going to be applying the new rules, which means we will be paying more tax.”