Anatole Kaletsky writes: January is usually expected to be a good month for stock markets, with new money gushing into investment funds, while tax-related selling abates at the end of the year. Although the data on investment returns in the United States actually show that January profits have historically been on only slightly better than the monthly norm, the widespread belief in a bullish “January effect” has made the weakness of stock markets around the world this year all the more shocking.

But the pessimists have a point, even if they sometimes overstate the January magic. According to statisticians at Reuters, this year started with Wall Street’s biggest first-week fall in over a century, and the 8% monthly decline in the MSCI world index made January’s performance worse than 96% of the months on record. So, just how worried about the world economy should we be?

Three fears now seem to be influencing market psychology: China, oil and the fear of a US or global recession.

China is surely a big enough problem to throw the world economy and equity markets off the rails for the rest of this decade. We saw this in the first four days of the year, when the sudden fall in the Chinese stock market triggered January’s global financial mayhem. But the Chinese stock market is of little consequence for the rest of the world. The real fear is that the Chinese authorities will either act aggressively to devalue the renminbi or, more likely, lose control of it through accidental mismanagement, resulting in devastating capital flight.

Such a scenario seemed quite plausible for a few weeks last summer, and it reemerged as a threat in the first two weeks of this year. By the end of January, however, market sentiment had moved back in favor of stability in China. This calm could be disrupted again if China’s foreign-exchange reserves show another huge monthly loss, and the authorities’ efforts to manage an orderly economic slowdown will remain the biggest source of legitimate concern for financial markets for many years ahead. But, judging by market behavior in the second half of January, the fear about China has subsided, at least for now.

That cannot be said about the market’s second great worry: collapsing oil prices. From the moment investors stopped panicking about China, in the second week of January, stock markets around the world started falling (and occasionally rebounding) in lockstep with the price of oil. Unlike the reasonable concern about China, market sentiment seems simply to have gotten the relationship between oil and the world economy wrong. In anything but the very short term, the correlation between oil prices and stock markets should be negative, not positive – and will almost certainly turn out that way in the years ahead.

When oil prices plunge by 10% daily, this is obviously disruptive in the short term: credit spreads in resources and related sectors explode, and leveraged investors are forced into asset fire sales to meet margin calls. Fortunately, market panic now seems to be subsiding, as oil prices reach the lower part of the $25-50 trading range that always seemed appropriate in today’s political and economic conditions. Now that oil prices are stabilizing at a reasonable long-term level, the world economy and non-commodity businesses should benefit. Low oil prices increase real incomes, stimulate spending on non-resource goods and services, and boost profits for energy-using businesses.

Yet, despite these obvious benefits, most investors now seem to believe that falling oil prices point to a collapse in economic activity, which brings us to the third fear haunting financial markets this winter: a recession in the global economy or the US.

Past experience suggests that oil prices are not a useful leading indicator of economic activity. In fact, if oil-price movements have any relevance at all in economic forecasting, it is as a contrary indicator. Every global recession since 1970 has been preceded by a big increase in oil prices, while almost every decline greater than 30% has been followed by accelerating growth and higher equity prices. The widespread view that plunging oil prices augur recession is a clear case of the belief that this time is different – a belief that typically takes hold in financial markets at the peaks and troughs of boom-bust cycles.

Finally, what about the falling stock market itself as an indicator of recession risks? One could quote the great economist Paul Samuelson, who famously quipped in the 1960s that the stock market had “predicted nine of the last five recessions.” There is, however, a less reassuring answer. While markets are often wrong in predicting economic events, financial expectations can sometimes influence those events. As a result, reality can sometimes be forced to converge towards market expectations, not vice versa.

This process, known as “reflexivity,” is a powerful force in financial markets, especially during periods of instability or crisis. To the extent that reflexivity works through consumer and business confidence, it should not be a problem now, because the oil-price collapse is a powerful antidote to the stock-market decline. Consumers are gaining more from cheap oil than they are losing from falling stock prices, so the net effect of recent financial turmoil on consumption should be positive – and stronger consumption should feed through to business revenues.

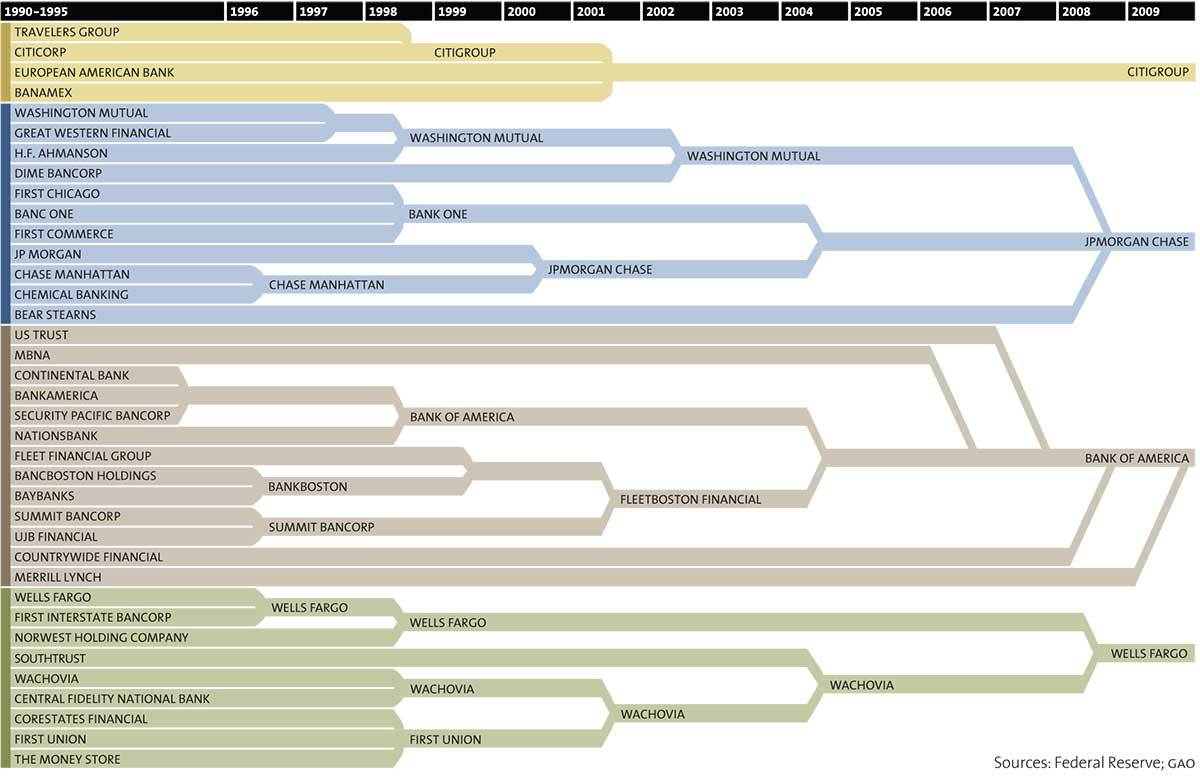

A greater worry is the workings of reflexivity within the financial system itself. Bankruptcies among small energy-sector companies, which are of limited economic importance themselves, are creating pressures in global banking and reducing the availability of credit to healthy businesses and households that would otherwise be beneficiaries of cheaper oil. Fears of a Chinese devaluation that has not happened (and probably never will) are having the same chilling effect on credit in emerging markets. Meanwhile, banking regulators are continuing to tighten lending standards, even though economic conditions suggest they should be easing up.

In short, nothing about the condition of the world economy suggests that a major slowdown or recession is inevitable or even likely. But a lethal combination of self-fulfilling expectations and policy errors could cause economic reality to bend to the dismal mood prevailing in financial markets.