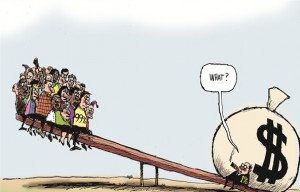

Peter Salisbury writes: Yemen was already a poor country when a 2011 popular uprising descended into inter-elite violence, bringing the economy to a standstill and tipping millions of people into poverty. Today, more than half of Yemenis live on $2 a day or less.

In November 2011, Ali Abdullah Saleh, Yemen’s president of 33 years, agreed to step down. He ceded power to his longtime deputy Abd Rabbu Mansour Hadi, who was tasked with guiding Yemen through a political transition that is meant to end with a referendum on a new constitution, followed by general elections.

This October, a new premier, Kahled Bahah, declared the economy to be a top priority for the supposedly technocratic cabinet he put together a month after being appointed. But that doesn’t mean that things are about to get better. There’s simply no money left.

The government is on course to spend $14 billion in 2014, almost three times its expenditures of a decade earlier. Meanwhile it’s been bringing very little in. Repeated attacks on a major oil export pipeline have cut off an important source of state revenues, while collection of taxes and payments to state utilities has been minimal.

The government’s response to the mounting fiscal crisis: Ask the neighbor for more money and keep on spending. The backers of the transition — the United Nations, the United States, the United Kingdom, and the states of the Gulf Cooperation Council — have imposed practically no accountability on the president, offering him seemingly limitless political support and refraining from criticism even as he has foundered.

Take the $435 million the Saudis gave to underwrite the cost of welfare payments. Although the money was transferred to the government in July, the fund has struggled to get the finance ministry to cough up the cash it needs to make quarterly payments.

Similarly, in December 2013, Qatar pledged $350 million towards reparations to military officers, civil servants, and landowners who were forcibly retired or had property stolen after 1994 north-south civil war.

A punishing debt repayment regime now accounts for around a fifth of all state spending. Yet Sanaa has spent practically nothing on investment and infrastructure improvements — the kind of spending that produces growth and jobs.

Keeping track of the money being spent hasn’t been a priority. International interventions in countries like Yemen come with their own moral hazards. The West feels the need to back transitional administrations and presidents because they see them as the best option for stability — and because that often serves western interests in other realms, such as security. Hadi, for example, has given firm support to U.S. counterterrorism efforts in Yemen.

That helps to explain the muted response to the missing money for welfare payments to Yemen’s large population of poor people. Members of the diplomatic community in Sanaa acknowledge that there’s an issue and talk about “pressuring” Hadi to resolve the problem, but say that they can’t push too hard because of the need to keep the president onside.