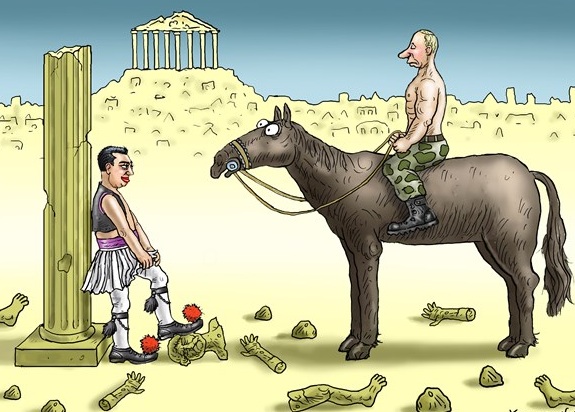

Kenneth Rogoff writes: Financial markets have greeted the election of Greece’s new far-left government in predictable fashion. But, though the Syriza party’s victory sent Greek equities and bonds plummeting, there is little sign of contagion to other distressed countries on the eurozone periphery. Spanish ten-year bonds, for example, are still trading at interest rates below US Treasuries. The question is how long this relative calm will prevail.

Greece’s fire-breathing new government, it is generally assumed, will have little choice but to stick to its predecessor’s program of structural reform, perhaps in return for a modest relaxation of fiscal austerity. Nonetheless, the political, social, and economic dimensions of Syriza’s victory are too significant to be ignored. Indeed, it is impossible to rule out completely a hard Greek exit from the euro (“Grexit”), much less capital controls that effectively make a euro inside Greece worth less elsewhere.

Some eurozone policymakers seem to be confident that a Greek exit from the euro, hard or soft, will no longer pose a threat to the other periphery countries. They might be right; then again, back in 2008, US policymakers thought that the collapse of one investment house, Bear Stearns, had prepared markets for the bankruptcy of another, Lehman Brothers. We know how that turned out.

True, there have been some important policy and institutional advances since early 2010, when the Greek crisis first began to unfold. The new banking union, however imperfect, and the European Central Bank’s vow to save the euro by doing “whatever it takes,” are essential to sustaining the monetary union. The European Stability Mechanism, which, like the International Monetary Fund, has the capacity to execute vast financial bailouts, subject to conditionality.

And yet, even with these new institutional backstops, the global financial risks of Greece’s instability remain profound.

In any scenario, most of the burden of adjustment will fall on Greece. Any profligate country that is suddenly forced to live within its means has a huge adjustment to make, even if all of its past debts are forgiven.

Once the crisis erupted and Greece lost access to new private lending, the “troika” (the IMF, the ECB, and the European Commission) provided massively subsidized long-term financing. But even if Greece’s debt had been completely wiped out, going from a primary deficit of 10% of GDP to a balanced budget requires massive belt tightening. Europe needs to be much more generous in permanently writing down debt and, even more urgently, in reducing short-term repayment flows.

Let’s face it: Greece’s bind today is hardly all of its own making.

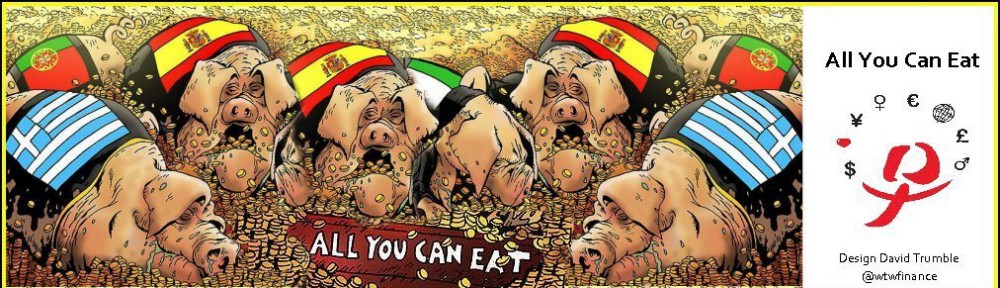

First and foremost, the eurozone countries’ decision to admit Greece to the single currency in 2002 was woefully irresponsible.

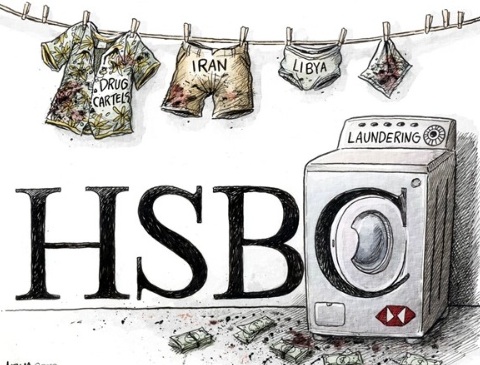

Second, much of the financing for Greece’s debts came from German and French banks that earned huge profits by intermediating loans from their own countries and from Asia.

Third, Greece’s eurozone partners wield a massive stick that is typically absent in sovereign-debt negotiations. If Greece does not accept the conditions imposed on it to maintain its membership in the single currency, it risks being thrown out of the European Union altogether.

Sooner rather than later, other periphery countries will also need help. Greece, one hopes, will not be forced to leave the eurozone, though temporary options such as imposing capital controls may ultimately prove necessary to prevent a financial meltdown. The eurozone must continue to bend, if it is not to break.