The Economist: The middle classes certainly know how to live in Brazil, with Copacabana and Ipanema just minutes from the main business districts a game of volleyball or a surf starts the day. Hedge-fund offices look out over botanical gardens and up to verdant mountains. But stray from comfortable districts and the sheen fades quickly. Favelas plagued by poverty and violence cling to the foothills. So it is with Brazil’s economy: the harder you stare, the worse it looks.

Brazil has seen sharp ups and downs in the past 25 years. In the early 1990s inflation rose above 2,000%; it was only banished when a new currency was introduced in 1994. By the turn of the century Brazil’s deficits had mired it in debt, forcing an IMF rescue in 2002. But then the woes vanished. Brazil became a titan of growth, expanding at 4% a year between 2002 and 2008 as exports of iron, oil and sugar boomed and domestic consumption gave an additional kick. Now Brazil is back in trouble. Growth has averaged just 1.3% over the past four years. A poll of 100 economists conducted by the Central Bank of Brazil suggests a 0.5% contraction this year followed by 1.5% growth in 2016.

Both elements of that prediction—the mild downturn and the quick rebound—look optimistic. The prospects for private consumption, which accounted for around 50% of GDP growth over the past ten years, are rotten. With inflation above 7%, shoppers’ purchasing power is being eroded. Hefty price rises will continue. Brazil is facing an acute water shortage; since three-quarters of its electricity comes from hydroelectric dams, this is sapping it of energy.

To avoid blackouts the government plans to deter use by raising prices: rates will increase by up to 30% this year. With the real losing 10% of its value against the dollar in the past month alone, rising import prices will bring more inflation.

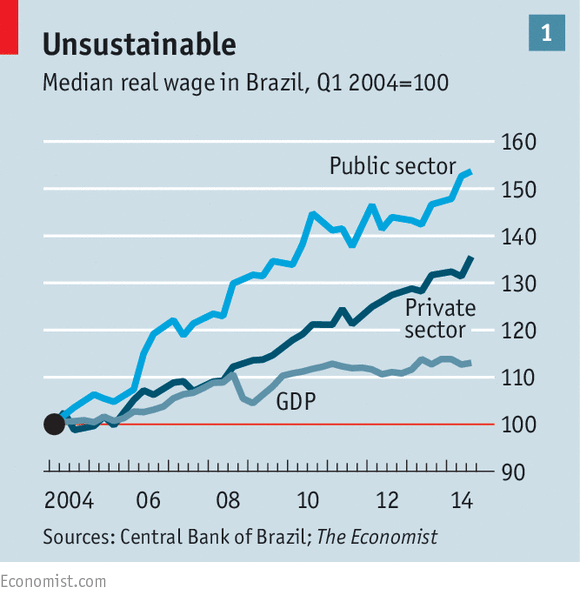

There is little hope of disposable income keeping pace. One reason is that Brazilian workers’ productivity does not justify further rises. In the past ten years wages in the private sector have grown faster than GDP; cosseted public-sector workers have done even better (see chart 1). Since Brazil’s minimum wage is indexed to GDP and inflation, a recession will freeze real pay for the millions who earn it. Brazil’s Dilemma