Anas Alhajji writes: Saudi Arabia wants it all: to salvage OPEC, achieve income diversification and industrialization, and preserve its market share in crude oil, petroleum products, petrochemicals, and natural gas liquids (NGLs). Whether the Saudis succeed will be determined largely by the shale-energy industry in the United States.

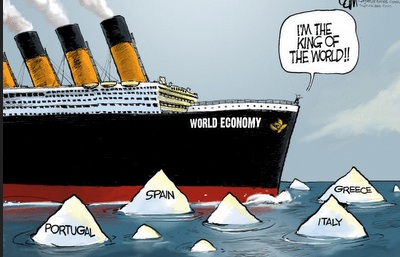

The US shale revolution divided OPEC according to the quality of its members’ crude oil. Exporters of light sweet crude – such as Algeria, Angola, and Nigeria – lost nearly all of their market share in the US, while exporters of sour or heavier crude, including Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, have lost little.

Because almost all crude oil produced by the Gulf States is sour, and most of the global surplus is sweet, any production cut by Saudi Arabia and its neighbors would not drive prices back up and rebalance the oil market. The only way to do that – and prevent an OPEC breakup – would be to reduce the production of light sweet crude, including by US producers, which would thus lose market share. If this occurred, oil prices could be expected to rise again relatively quickly.

If, however, Saudi Arabia remains more committed to its strategic development objectives, low oil prices could persist. Since the 1970s, several OPEC members, led by Saudi Arabia, have worked to diversify their industrial base by promoting sectors with a comparative advantage, such as petrochemicals, and building mega-refineries to enable the export of value-added products. At the same time, to boost revenues, they expanded exports of NGLs, which are not counted in OPEC quotas.

But just when these countries were beginning to achieve success, the US shale revolution emerged, threatening all three of their main strategic objectives. The key to the competitiveness of Saudi Arabia’s petrochemical industry was its use of natural gas and ethane, which was far less expensive than the oil product naphtha on which its global competitors depended. Now that the US is producing massive amounts of low-price natural gas and ethane, Saudi Arabia’s competitive advantage – and market share – is beginning to deteriorate.

The same goes for refining. Since the US does not allow exports of crude oil, the shale revolution pushed down the US benchmark price, the West Texas Intermediate, relative to international crude prices, sometimes with differentials as wide as $20. US refiners took advantage of lower prices to increase their exports of petroleum products – so much so, that they are now threatening the market share of Saudi refineries in Asia and elsewhere.

Likewise, US companies have increased NGL production considerably, enabling the country to slash its liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) imports and expand its NGL exports significantly. As a result, Saudi Arabia has lost market share to US producers in Central and South America.

But the recent collapse in oil prices could change this dynamic. In refusing to cut its own production, Saudi Arabia seems to be hoping that low oil prices will drive down investment in US shale energy, undermining production growth there.

Low prices may already have contributed to delays in America’s decision to begin exporting crude oil, as well as to the political viability of US President Barack Obama’s veto of the Keystone XL pipeline, intended to transport oil from the Canadian tar sands to the Gulf of Mexico for export. Add to that the delay in the opening of the Mexican energy sector, and it seems that low oil prices could amount to a net gain for the Kingdom.

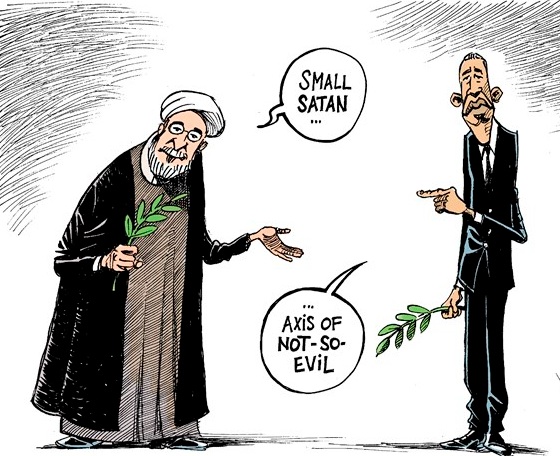

Though Saudi Arabia’s motivation in not cutting production was probably almost entirely economic, low oil prices could also offer distinct political advantages. Most notably, the decline in prices is creating serious challenges for Iran, the Kingdom’s main rival in the region, as well as for the unstable, oil-dependent economies of Russia and Venezuela. None of these countries has adequate savings to cushion the blow of reduced revenues.

Under these circumstances, it seems likely that Saudi Arabia will continue to refuse to cut oil production, leaving prices low until market forces trigger a rebound. And even then, the price increase could be limited. After all, game theory dictates that, once the surplus is eliminated, the dominant producer must prevent oil prices from rising high enough to cause it to lose market share again. That means that Saudi Arabia will try to compel non-OPEC countries, mainly in North America, to keep oil-production increases commensurate with growth in global demand.

In short, it is in Saudi Arabia’s interest for oil prices to rise high enough to sustain its own economy, but not so high that they can sustain significant increases in non-OPEC supply. In order to keep prices in this ideal range, Saudi Arabia may even increase production again.

Over the next few years, US producers are likely to retrench, focus on sweet spots, improve technology, reduce costs, and increase production once again. At that point, Saudi Arabia’s current strategy may no longer be adequate to sustain its market dominance.