What kept the angst in check was that while robots were increasingly doing complex things, like IBM’s Deep Blue beat world champion Garry Kasparov at chess, they couldn’t get the hang of simple things. Computers could make human tasks easier but they could not do away with the human altogether and so a Nobel Laureate was able to say that “we see the computer age everywhere except for the productivity statistics”.

Category Archives: Finance

Should the Carry Trade be Regulated?

Harold James writes” During the early years of the global financial crisis, exchange rates were the least interesting part of the macroeconomic debate. A French proposal in 2011 for a sweeping reform of the international monetary regime went nowhere. Today, the subject has become the focus of intense anxiety – and with good reason.

Currency wars are a reminder of the fragility of the process of globalization.

The expectation that interest rates in the United States will rise is driving up the value of the dollar, even as monetary easing in Japan and Europe is pushing down the yen and the euro.

The euro’s depreciation has been greeted with delight by Europe’s business leaders. But in the US, where the dollar’s gains are threatening to choke off economic recovery, officials at the Federal Reserve are expressing signs of concern.

The swing in exchange rates could have an impact that extends far beyond the short-term rebalancing of the global marketplace.

Indeed, surges in the dollar’s value have long coincided with increased political pressure for trade protectionism. After all, the most obvious way to compensate for the apparent overvaluation of a country’s currency is by imposing import restrictions.

In the mid-1980s, the dollar’s appreciating exchange rate undermined US competitiveness, inaugurating a period of rapid and painful deindustrialization.

If anything, today’s exchange-rate swings are likely to be more extreme, and to last longer, than the surge in the dollar’s value in the 1980s or the volatility of the 1930s, when, in the aftermath of the financial crash that triggered the Great Depression, countries competed to devalue their currencies.

The problem is what is known as the carry trade, a common financial strategy in which an investor borrows money in a currency subject to a low interest rate in order to buy assets in a currency subject to a higher rate. The interest-rate differential, often combined with high amounts of leverage, provides a profit when the loans are paid off.

When exchange rates are stable and predictable, the carry trade is relatively safe. But this is rarely the case. For starters, the practice has the tendency to push exchange rates further apart, as investors sell the currency in which they borrowed to make their purchases.

The large corporate borrowers engaged in the carry trade consider themselves sophisticated investors, capable of predicting when exchange rates are about to reverse. Unfortunately, this only increases the risk, boosting the possibility of a sudden reversal as money pours back into the borrowed currency in an attempt to repay loans before the exchange rate soars to loss-generating levels.

The dangers are very real.

There is one historical precedent that could serve as a model, should we be able to muster the political will to consider it. In the 1930s, John Maynard Keynes championed limits on the movement of capital in order to blunt the more damaging consequences of globalization. The equivalent today would be to introduce regulations on the carry trade. Policymakers would do well to consider this option – before it is too late.

What Happens When Money Costs Nothing?

Daniel Gros writes: The developed world seems to be moving toward a long-term zero-interest-rate environment. Though the United States, the United Kingdom, Japan, and the eurozone have kept central-bank policy rates at zero for several years already, the perception that this was a temporary aberration meant that medium- to long-term rates remained substantial. But this may be changing, especially in the eurozone.

Strictly speaking, zero rates are observed only for nominal, medium-term debt that is perceived to be riskless. But, throughout the eurozone, rates are close to zero – and negative for a substantial share of government debt – and are expected to remain low for quite some time.

In Germany, for example, interest rates on public debt up to five years will be negative, and only slightly positive beyond that, producing a weighted average of zero. Clearly, Japan’s near-zero interest-rate environment is no longer unique.

To be sure, the European Central Bank’s large-scale bond-buying program could be suppressing interest rates temporarily, and, once the purchases are halted next year, they will rise again. But investors do not seem to think so.

The eurozone seems stuck with near-zero rates at increasingly long maturities. What does this actually mean for its investors and debtors?

Japanese savers have been benefiting from this phenomenon for more than a decade, reaping higher real returns than their counterparts in the US, even though Japan’s near-zero nominal interest rates are much lower than America’s.

Nonetheless, nominal rates are negligible, they flatter profit statements, while balance-sheet problems slowly accumulate.

Given that balance-sheet accounting is conducted according to a curious mix of nominal and market values, it can be opaque and easy to manipulate. If prices – and thus average debt-service capacity – fall, the real burden of the debt increases.

In an environment of zero or near-zero interest rates, creditors have an incentive to “extend and pretend” – that is, roll over their maturing debt, so that they can keep their problems hidden for longer.

Japan’s experience illustrates this phenomenon perfectly. At more than 200% of GDP, the government’s mountain of debt seems unconquerable. But that debt costs only 1-2% of GDP to service, allowing Japan to remain solvent. Likewise, Greece can now manage its public-debt burden, which stands at about 175% of GDP, thanks to the ultra-low interest rates and long maturities (longer than those on Japan’s debt) granted by its European partners.

In short, with low enough interest rates, any debt-to-GDP ratio is manageable. That is why, in the current interest-rate environment, the Maastricht Treaty’s requirement limiting public debt to 60% of GDP is meaningless.

In fact, near-zero interest rates undermine the very notion of a “debt overhang” in countries like Greece, Ireland, Portugal, and Spain. While these countries did accumulate a huge volume of debt during the credit boom that went bust in 2008, the cost of debt service is now too low to have the impact – reducing incomes, preventing a return to growth, and generating uncertainty among investors – that one would normally expect. Today, these countries can simply refinance their obligations at longer maturities.

Financial and Economic Markets Might Mix Like Oil and Oil!

Open letter to the FInancial Times:

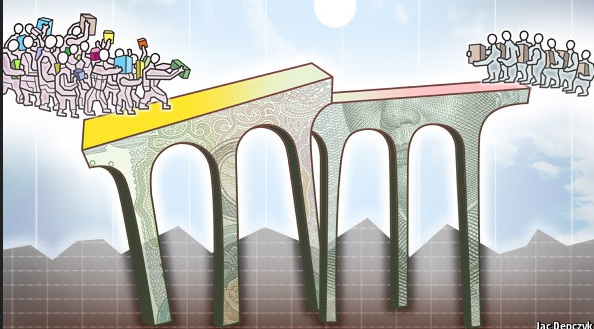

Sir, The European Central Bank forecasts unemployment in the eurozone to remain at 10 per cent even after €1.1tn of quantitative easing. (FT View, March 25). This is hardly surprising: the evidence suggests that conventional QE is an unreliable tool for boosting GDP or employment.

Bank of England research shows that it benefits the well-off, who gain from increasing asset prices, much more than the poorest. In the eurozone, where interest rates are at rock bottom and bond yields have already turned negative, injecting even more liquidity into the markets will do little to help the real economy.

There is an alternative. Rather than being injected into the financial markets, the new money created by eurozone central banks could be used to finance government spending (such as investing in much needed infrastructure projects); alternatively each eurozone citizen could be given €175 per month, for 19 months, which they could use to pay down existing debts or spend as they please. By directly boosting spending and employment, either approach would be far more effective than the ECB’s plans for conventional QE.

The ECB will argue that this approach breaks the taboo of mixing monetary and fiscal policy. But traditional monetary policy no longer works. Failure to consider new approaches will unnecessarily prolong stagnation and high unemployment. It is time for the ECB and eurozone central banks to bypass the financial system and work with governments to inject newly created money directly into the real economy.

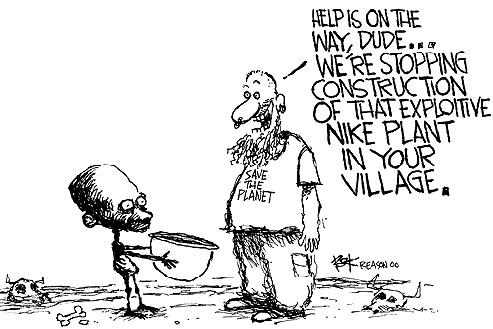

Must Manufacturing and Growth Go Together?

Uri Dadush writes: Manufacturing is often seen as the key to sustainable export and productivity growth in developing countries. This column argues that, while manufacturing played a key role in some countries’ development, high growth can be sustained without relying primarily on manufacturing. A process of learning, productivity improvement, and investment that touches all sectors characterises the most successful economies. Policies that artificially favour manufacturing should instead give way to maximising learning from the frontier in all sectors of the economy.

The manufacturing sector has been a driver of development across at least the last three centuries, but its importance appears to be declining. The long-standing belief that manufacturing must lead the growth process, as set out for example by Rodrik (2015), rests on two critical assumptions:

- First, that manufacturing is the only sector capable of sustainably achieving scale in the world market (downplaying the role of natural resources and other sectors); and

- Second, that it is also the main sector capable of achieving sustained high productivity growth.

So, the argument goes, the rest of the economy, stodgy, unreliable, or confined to the home market, cannot grow unless pulled by the manufacturing sector. But neither of the critical assumptions holds up nowadays, if they ever did. Countries have shown that they can find many avenues to achieve scale on world markets, of which manufacturing is one, and, with the exception of some services that must still be provided face-to-face, rapid productivity improvements are being achieved in all sectors of the economy, often faster than in manufacturing. As I argue in Dadush (2015), this is cause for hope, not despair.

ICT (Information and Communications Technology) has created large new growth and high-productivity sectors in ‘modern’ services – such as finance, telecommunications, software, and business process outsourcing – and also made many services, previously provided face-to-face, such as retailing and banking, storable, divisible and tradable, boosting productivity. Exports of modern services have outpaced those of manufactures by a wide margin since 2000.

Globalisation, ICT, and the associated phenomenon of rapid catch-up growth of developing countries, have opened up many new avenues for earning foreign exchange, boosted the demand and supply of natural resources, and created opportunities in finer combinations of resources, services, and manufactures (‘tasks’) along the international value chain. Many economies that are poor in natural resources and too small or distant to be competitive in manufacturing have found that they can rely on migrant remittances, tourism, and investment links with their diaspora for foreign exchange and growth. Is Manufacturing Necessary for Developing Nations

Monetary Policy and Worldwide Growth

The Dallas Federal Reserve reports: In 2014, global real gross domestic product (GDP) grew 3 percent year over year, its lowest value since 2009. Growth in emerging markets was sluggish at 4.3 percent, the slowest pace since 2003 (excluding 2009), led by poor growth in Russia and Brazil. Advanced foreign economies also expanded modestly at 1.8 percent. Still, the global economy grew more quickly in fourth quarter 2014 than for the year as a whole at a 3.4 percent annualized rate, reflecting positive growth in the euro area and Japan. Forward-looking indicators such as the Purchasing Managers Index, which tracks the health of the manufacturing sector, ticked up in February for advanced foreign economies, suggesting a possible pickup.

Exceptionally low oil prices have contributed to lower inflation globally. Inflation in advanced foreign economies fell from 2 to 1 percent between June and December 2014. In 2015, accommodative monetary policy and low oil prices may provide a much-needed boost to global growth. Monetary Policy and Global Growth

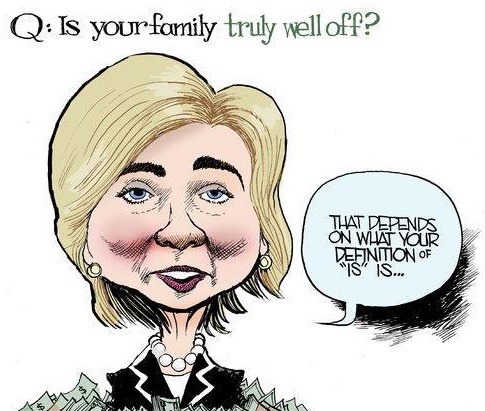

Issues for Hillary Clinton

Former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton will announce her run for the presidency tomorrow. Here are the words we are looking for:

Inequality

End Glass Steagall

Break up of banks

Education reform

Afforable housing for all

Diversion of public funds by corruptioin

Commodities trading

High speed trading

Inclusive foreign policy

Add to the list on twitter or below.

Add to the list on twitter or below.

Turkey’s Erdogan

Stephen Cook writes: t is eight weeks before Turkey’s general elections, the end of a stretch that has lasted a little more than a year during which Turks will have gone to the polls three times to elect their Mayors, President, and now legislators. The extended electoral season, made difficult by Turkey’s polarization, has not dampened the Istanbul-Ankara elite’s appetite for rank speculation, however. In years past, much of this chatter centered on parties and politicians who were going to save Turkey from whatever crisis of governance had befallen the country. There was the businessman Cem Uzan and his Youth Party in 2002; the dream team of Ismail Cem and Kemal Dervis, who were going to lead the New Turkey Party to victory also in 2002; Kemal Kilicdaroglu, the man to reverse the slide of the Republican People’s Party into the party of Izmir and certain Istanbul neighborhoods; and, of course, Abdullah Gul, the man to wrest control of the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) from Recep Tayyip Erdogan. Uzan, however, was convicted of fraud in the United States and now lives in France, the New Turkey Party received a paltry 1.2 percent of the vote, Kilicdaroglu has presided over one defeat after the next, and Gul moved quietly from Ankara’s Cankaya Palace to Istanbul, where he seems to be enjoying retirement. So much for saving Turkey.

As this year’s vote approaches, speculation has focused not on a would-be charismatic leader riding to the rescue, but rather on the relationship between Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu and President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, and what it means for the future of Turkish politics. There seems to be a consensus among Ankara insiders and foreign observers that all is not well between the Prime Minister and the President. The deteriorating relationship between Davutoglu and Erdogan has given life to the idea that there is now a faction within the AKP capable of checking Erdogan and his apparent voracious appetite for power. It seems that the two most powerful figures in Turkish politics barely tolerate each other, but Davutoglu and his emerging faction—if it exists—do not stand a chance. Erdogan is, and will likely remain, the sun around which Turkish politics revolves. Turkey’s Erdogan

Supporting the AIB?

Latin America’s Fit in Global Trade

The Doha Round is at a standstill, the World Trade Organization is increasingly looking weaker, and new initiatives such as the Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) and Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) appear to be changing the roadmap of global trade negotiations. The two major trading blocks in Latin America—the Pacific Alliance (Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Peru) and Mercosur (Brazil, Argentina, Venezuela, Paraguay and Uruguay)—appear to have different underlying orientations and philosophies towards trade, markets and investment. As a consequence, they are pursuing increasingly separate courses and different strategies towards global trade. What are the implications of this perceived gap as Latin America seeks to position itself in the new dynamics of global trade negotiations?

On March 25, the Latin America Initiative at Foreign Policy (LAI) and the Brookings Global-CERES Economic and Social Policy in Latin America Initiative (ESPLA) hosted a discussion on Latin America’s evolving role in the global trade environment. Panelists included Antoni Estevadeordal, manager of Integration and Trade at the Inter-American Development Bank; Joshua Meltzer, fellow in Global Economy and Development at Brookings; and Jeff Schott, senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics. Brookings Senior Fellow and ESPLA Director Ernesto Talvi provided introductory remarks and Brookings Senior Fellow and LAI Director Harold Trinkunas moderated the discussion. Global Trade; How Does Latin American Fit In?