Joseph Nye writes: As Europe debates whether to maintain its sanctions regime against Russia, the Kremlin’s policy of aggression toward Ukraine continues unabated. Russia is in long-term decline, but it still poses a very real threat to the international order in Europe and beyond. Indeed, Russia’s decline may make it even more dangerous.

The threat posed by Russia extends far beyond Ukraine. After all, Russia is the one country with enough missiles and nuclear warheads to destroy the US. As its economic and geopolitical influence has waned, so has its willingness to consider renouncing its nuclear status. Indeed, not only has it revived the Cold War-era tactic of sending military aircraft unannounced into airspace over the Baltic countries and the North Sea; it has also made veiled nuclear threats against countries like Denmark.

Russia’also benefits from its enormous size, vast natural resources, and educated population, including a multitude of skilled scientists and engineers.

But Russia faces serious challenges. It remains a “one-crop economy,” with energy accounting for two-thirds of its exports. And its population is shrinking – not least because the average man in Russia dies at age 65, a full decade earlier than in other developed countries.

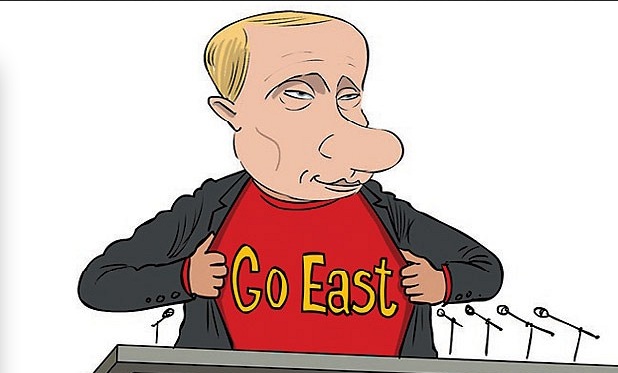

Instead of developing a strategy for Russia’s long-term recovery, Putin has adopted a reactive and opportunistic approach – one that can sometimes succeed, but only in the short term.

Russia’s problem is not just Putin. Though Putin has cultivated nationalism. Other high-level figures – for example, Dmitry Rogozin, who last October endorsed a book calling for the return of Alaska – are also highly nationalistic, a successor to Putin would probably not be liberal. The recent assassination of former Deputy Prime Minister and opposition leader Boris Nemtsov reinforces this assumption.

So Russia seems doomed to continue its decline – an outcome that should be no cause for celebration in the West. States in decline – think of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1914 – tend to become less risk-averse and thus much more dangerous. In any case, a thriving Russia has more to offer the international community in the long run.

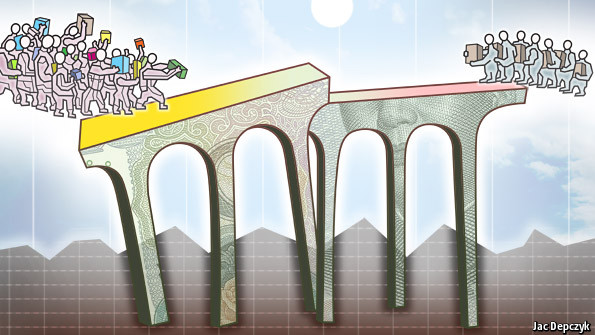

Though sanctions are unlikely to change Crimea’s status or lead to withdrawal of Russian soldiers from Ukraine, they have upheld that principle, by showing that it cannot be violated with impunity.

On the other hand, it is important not to isolate Russia completely, given shared interests with the US and Europe relating to nuclear security and non-proliferation, terrorism, space, the Artic, and Iran and Afghanistan. No one will benefit from a new Cold War.

Designing and implementing a strategy that constrains Putin’s revisionist behavior, while ensuring Russia’s long-term international engagement, is one of the most important challenges facing the US and its allies today. For now, the policy consensus seems to be to maintain sanctions, help bolster Ukraine’s economy, and continue to strengthen NATO (an outcome that Putin undoubtedly did not intend). Beyond that, what happens is largely up to Putin.