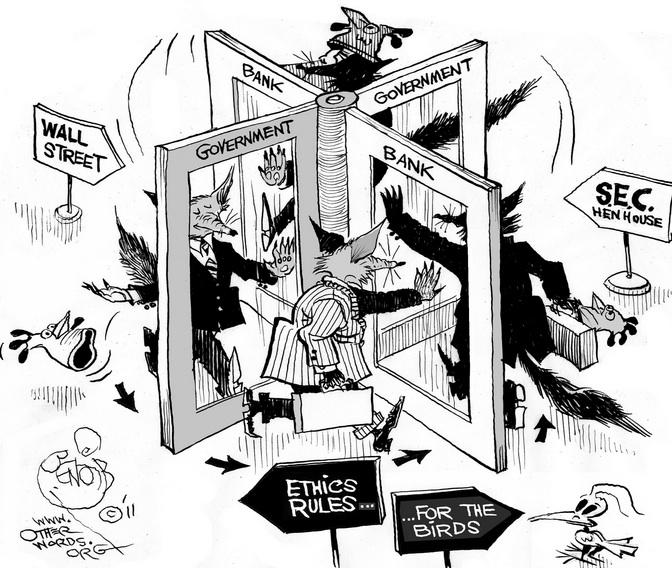

Ken Workman discusses reaction to the true but politically incorrect remark of Jeroen Djisselbloem. The fact—and the fear—is that the Eurogroup is changing expectations again: When they bailed out Greece, creditors got restructured, but Europe promised it was a one-time only thing. The ECB bailout of Spain was different: You guys recapitalize the banks, creditors stay whole, and the ECB provides the financing. When Cyprus, and its role as Russia’s offshore bank came along, European leaders responded by reverting to the Greek model: Creditors got “bailed-in” and had to take losses.

Customers at banks in Spain and Italy and France now realize that if their countries and banks end up in need of further financial assistance to stay in the euro zone, the private sector might have to take losses. This is already causing bank stock prices to drop, prompting a quick walk-back (pdf) that left everyone confused.

Customers at banks in Spain and Italy and France now realize that if their countries and banks end up in need of further financial assistance to stay in the euro zone, the private sector might have to take losses.

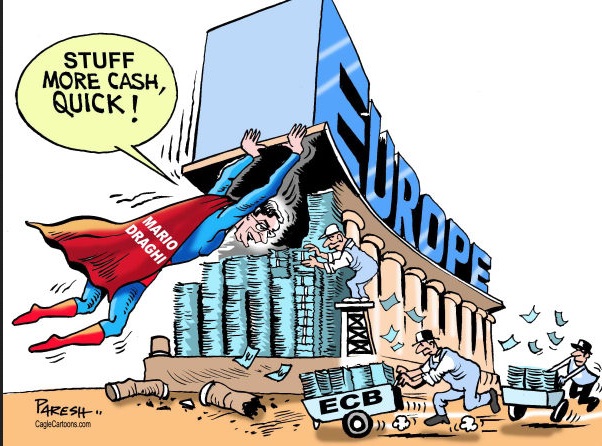

The problem is that while Cyprus is special, it’s not that special. Germans don’t want to bailout Russian depositors, but they also don’t want to bail out anyone. The Spain model isn’t working and the expectation that it will means disappointment. A euro zone mired in recession is not going to be able to out-grow its debt problem with a weak financial system. The EU needs a banking union, something the Eurogroup has already begun work on. Recognizing reality may make markets nervous, but to solve the crisis, public and private creditors will have to pay up.

That doesn’t make Cyprus ideal by any stretch of the imagination. Cypriots would probably be better off leaving the euro altogether. And the haphazard assembly of its bailout has left only two real principles intact: the euro will not be allowed to fail, and creditors will likely need to help with that. Balancing crisis management (stopping bank runs) with reform (recapitalizing banks) is never easy, but after four years it might be worth thinking more clearly about the tensions between the two.