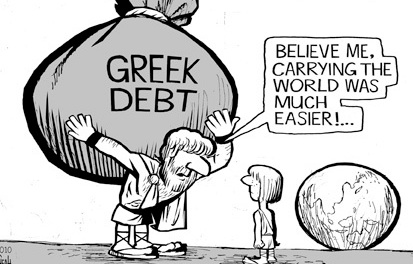

Slovenian finance chief Dusan Mramor led the calls at a meeting of the bloc’s 19 finance chiefs on Friday to consider a “plan B” to mitigate the fallout if negotiations with Greece fail.

As Greece struggles to pay pensions and salaries, its government has failed to present a plan to revamp its economy that passes muster with euro-area officials who are withholding further aid.

In February, finance ministers gave the Greek government until the end of June to complete the deal and said they expected a list of reforms by the end of April.

“Some countries have said, because of their concern on the lack of progress and the attitude on the Greek side, ‘if it continues like this, we will really get into trouble,’” Dutch Finance Minister Jeroen Dijsselbloem said “In that context plan B has been mentioned.”

Still, ministers were left frustrated that European Economic Commissioner Pierre Moscovici clamped down on discussions of a backup plan. They went on to air their concerns without him, one of the people said.

Finance chiefs aren’t saying in public that they’re contemplating alternative outcomes because that would send the message to markets that it’s game over, the person said.

“The central scenario is that in the Greece case we’re going to reach an agreement,” Spanish Economy Minister Luis de Guindos told reporters on Saturday. “That’s the only one that we’re considering.”

Varoufakis, who was attacked by his colleagues for his handling of the negotiations, joined Moscovici’s effort to prevent others in the group taking precautions in case the talks fail.

While finance ministers’ immediate concern is how to keep Greece in the euro area, if talks over refinancing break down, failure to prepare for a Greek default also risks reawakening the contagion threat that shook the bloc during the darkest days of the debt crisis.

Technical inspectors assessing the needs of Greece’s economy on behalf of the EU and International Monetary Fund told Friday’s meeting that they need to have better access to officials with political responsibility in Athens in order to speed up the process, according to de Guindos.

The dilemma for finance ministers is that just raising the prospect of a plan B risks making it a self-fulfilling prophecy.