Charles Gasparino writes: The problem isn’t Dimon’s mansplaining. It’s that Warren is telling a truth no one else will tell: Big banks aren’t free-market at all.

Warren says these big bank institutions should be broken up by the government out of fear that the system could implode as it did in 2008.

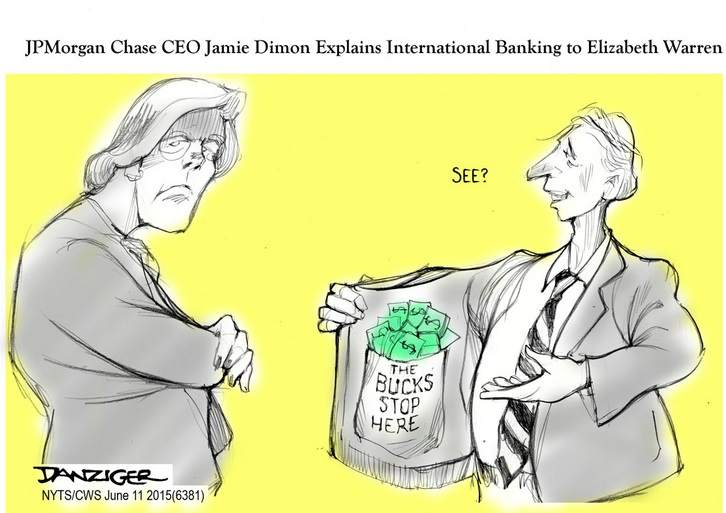

Dimon says the good senator should stick to making sure the Community Redevelopment Act is enforced and other pet lefty projects because she doesn’t “fully [understand] the global banking system.”

For once we have a leader in Washington, namely Warren, telling us what most of the political class and the bankers won’t: The banks are not free-market at all. They are big, government-protected entities that will be bailed out the next time a 2008 scenario comes around.

And the best way to make sure they don’t end up costing the taxpayers more money will be to make them smaller, which is about as close to a free-market statement as you might find on this subject, courtesy of Sen. Warren.

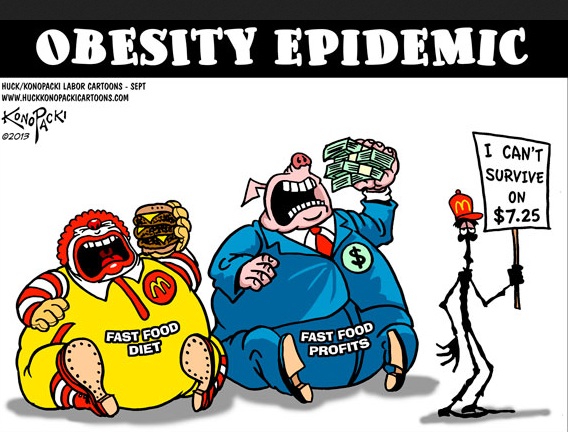

The dirty secret in Washington and Wall Street that Warren is exposing is that banks like JP Morgan, Citi, and B of A will always be on the government’s protected-species list because of a little thing known as deposit insurance, which covers bank deposits up to $250,000.

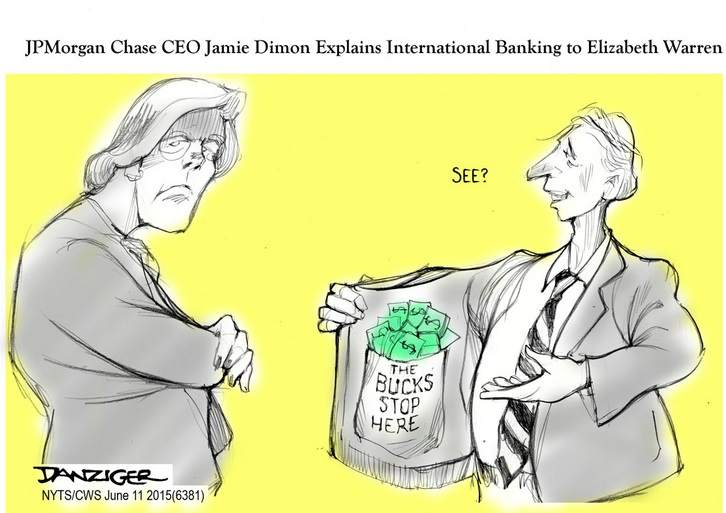

These banks just don’t take in deposits and lend them out so people can buy homes and so on anymore. Thanks in large part to Hillary Clinton’s husband, banks combine these commercial banking activities with Wall Street risk-taking.

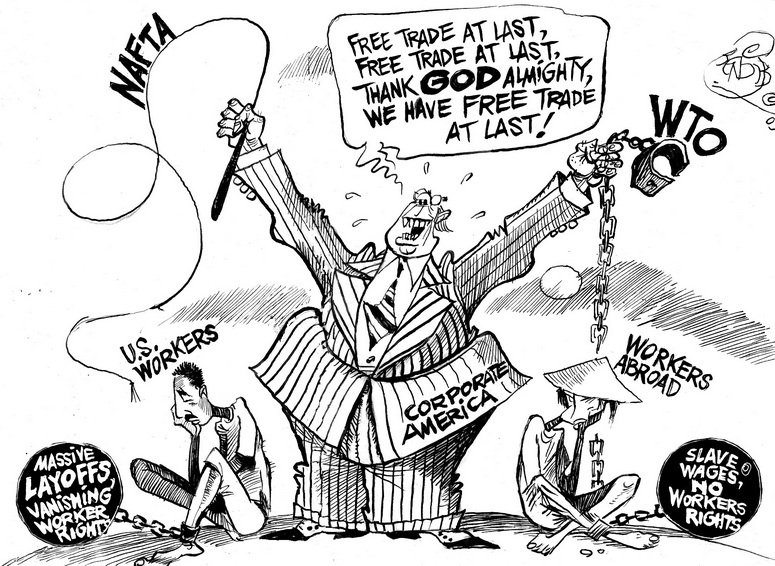

Meanwhile, JP Morgan has a whopping $1.4 trillion in deposits. A massive screwup on its trading desk or some 2008-like event that leads to insolvency could mean the taxpayer is on the hook for a chunk of that money—a number, I might add, that could dwarf the $800 billion stimulus package President Obama blew through during the Great Recession.

What free-marketer would allow the American taxpayer to subsidize Jamie Dimon’s risk-taking?

Again, the Dodd-Frank Act was supposed to get rid of Too Big to Fail, but the reality that Warren is at least honest about is that it hasn’t:

What’s great about the Warren vs. Dimon feud is that it both exposes Wall Street’s real crony capitalism roots and the hypocrisy of Hillary Clinton remaking herself in the Elizabeth Warren class-warrior mode. Yes it was Bill Clinton who enacted one of the least thought-out banking laws back in 1999 that made it legal to combine commercial-banking activities with Wall Street-style risk-taking.

The result of what was known as the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Financial Services Modernization Act was the permanent dismantling of the Glass-Steagall Act, which made it illegal to mix bond trading with deposit-taking.

The law paved the way for the creation of the financial supermarket known as Citigroup, which would go on to hire Clinton Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin as one of its top executives and board members. Hillary Clinton has collected hundreds of thousands of dollars in speaking fees from bankers.

She won’t of course, but Warren should be given credit for explaining just how protected and coddled banks still are in many ways, thanks to the Clintons and their unholy alliance with Wall Street. Dimon’s comments about Warren are shocking only because they were made honestly and publicly.

Why should taxpayers subsidize his paycheck, which goes up with every successful trade? My advice: If Jamie Dimon wants to roll the dice in the derivatives markets, he should first be forced to give up his access to FDIC insurance on JP Morgan’s deposits.

I’m pretty sure Adam Smith and Elizabeth Warren would agree.