Holger Nehring writes: In the week before the Greek referendum, leading German tabloid BILD conducted its own referendum on what should happen to Greece. The question:“Should we support Greece with further taxpayers’ billions?”, pointed out that Germany had already poured €88 billion down the Greek sinkhole.

Almost 90% of BILD readers voted No. Another poll printed in the same paper on Saturday suggested that 78% felt compassionate towards the Greek population. And 56% believed German would be unaffected by the outcome of the referendum and any consequences this may have.

Like many Greeks, Germans still believe – optimistically – that their government has the sovereignty to make unilateral decisions and that they are shielded against the vagaries of the international economic and financial system. But they are also still keen to show that they are the star pupils in European solidarity: this explains the high levels of compassion for the Greek population. In tune with this the German vice-chancellor, – a social democrat – has just offered to consider humanitarian aid for Greece, should it be required.

What does this mean for German politics? The Greek No is a major defeat for the chancellor, Angela Merkel, both domestically and internationally. Most politicians from Merkel’s Christian Democrats are pessimistic about the possibility of a new deal and many have interpreted the result as a vote against the euro, if not a vote against a European Union. Only the small quasi-socialist Left Party, whose parliamentary party had even supported a previous austerity deal for Greece, and, to a lesser extent, the Greens, also much diminished since the last election, are arguing in favour of Syriza.

All this poses a massive problem for Merkel. She is so far only on record saying cryptically that she “respected” the outcome of the Greek vote, and it is very likely that she will push for further negotiations.

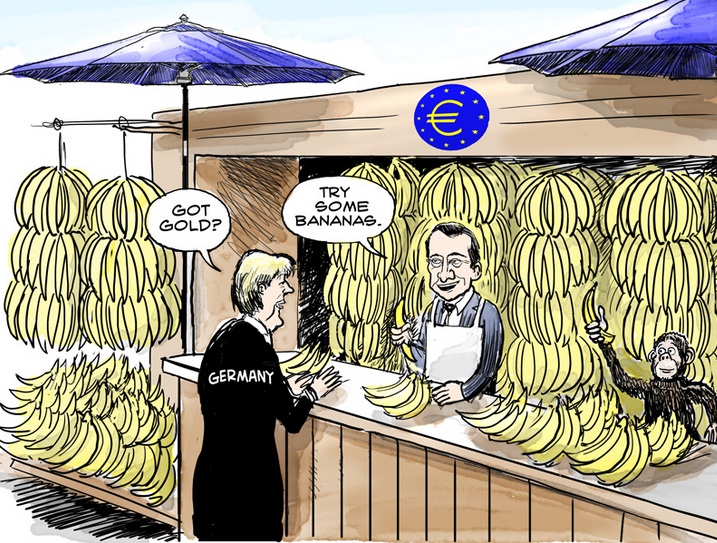

At the same time, Merkel wants to be seen as powerful negotiator, not the deal breaker. Her legacy as a pro-European, the East German who has brought the reunified Germany into a renewed European Union, is at stake. This is why her finance minister Wolfgang Schäuble was the designated bad cop in negotiations. But this will come at a cost: the vast majority of the German population and her own party are pulling her away from clinching a deal

The hard line that Schäuble took towards Greece is hugely popular in the German population. And, if anything, his support base in Merkel’s Christian Democratic Union (CDU) is probably greater than Merkel’s own.

Merkel could wait for a long time, build up the pressure and then use that pressure to clinch a deal at the very last minute, claiming that there was the need to act due to some higher authority, which places a disclaimer on her direct responsibility, just in case.

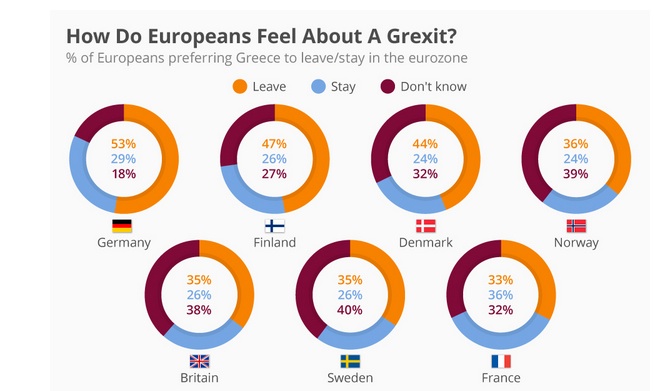

Merkel now faces the choice of pleasing her electorate and being remembered as the person who finished off a key element of European integration; or trying to rescue Greece, which will stoke euroscepticism in Germany and is likely to reduce the voter base for her party. There is no current alternative to the CDU on the right.. But it is only a matter of time until full-scale anti-EU populism seen in France and the UK will come to Germany.

Merkel’s legacy is tied to the fate of the eurozone. Focused on tactics rather than strategy, Merkel’s way of dealing with things has not worked out well in this context. She has run up against structures that proved immune to her tactics: the highly complex machinery of the EU, with its many committees, forums, lobby groups and difficult decision making, and the popular will of another EU member state.

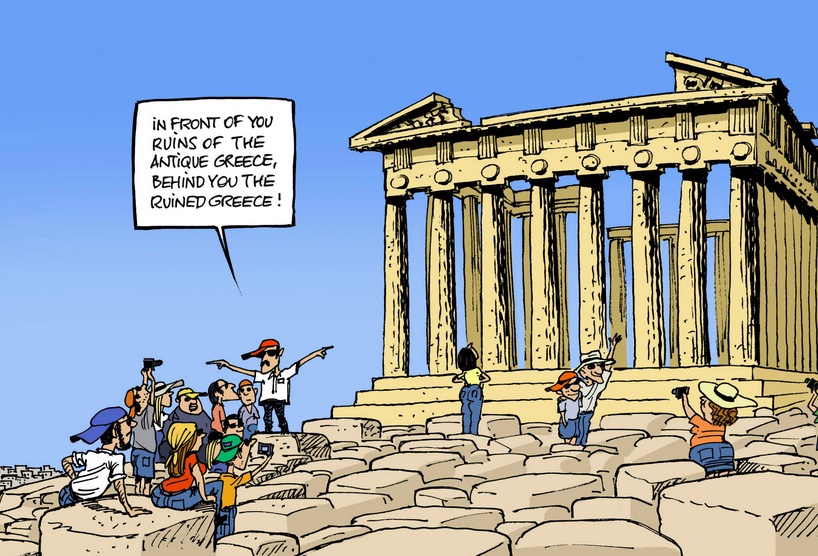

The crisis in Greece is an economic and financial disaster that may turn into a humanitarian crisis. It is also, fundamentally, a crisis of national sovereignty in the context of the European Union: one popular will is pitted against another, without an effective means of mediating between the two.

Merkel can now show true leadership rather than just tactical manouevres: starting an open debate about the parameters of European integration and about the German model. There is, still, a tiny bit of time left for Merkel to find her moment.