Steve Case writes: Most people didn’t see the need to be connected; only 3 percent of U.S. households were online when I started, averaging less than one hour of usage per week. It was not clear why people would want to communicate, buy things or gather information through a computer. Online services were pricey, slow, confusing and of limited usefulness.

It was a slow and steady ascension with many near-death experiences. We went through several layoffs and pivots, trying to identify a viable path forward. When we went public in 1992 — after seven years of hard work — we still had less than 200,000 subscribers.

But we stayed with it, and eventually people decided they did want to get connected. By 2000, when we celebrated our 15th birthday, we had 25 million subscribers and nearly 10,000 employees, and about half of the consumer Internet traffic,

But looking back 30 years later, with nostalgia and pride, I am struck by how our journey is about to be repeated by the next generation of entrepreneurs who are tackling some of the world’s most pressing challenges. Indeed, the Internet’s future may very well look a little like its past.

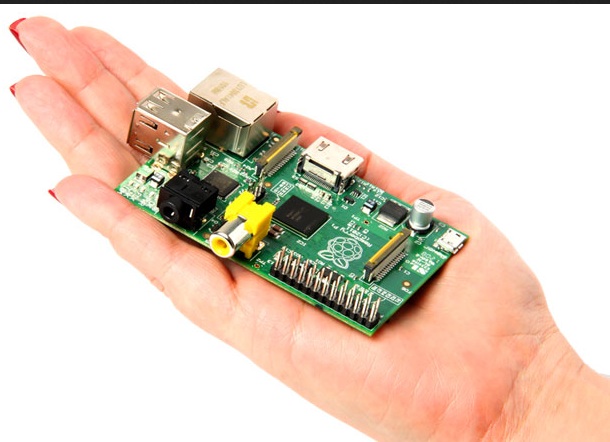

The first wave was the period of building the infrastructure, connections and awareness that ushered in a connected world. During this time, companies such as Cisco, WorldCom, IBM, Microsoft, Netscape and AOL were constructing the on-ramps to the information superhighway.

Iin the second wave, as the market shifted from narrow-band, dial-up phone connections to broadband and the disruption of media and commerce took hold.

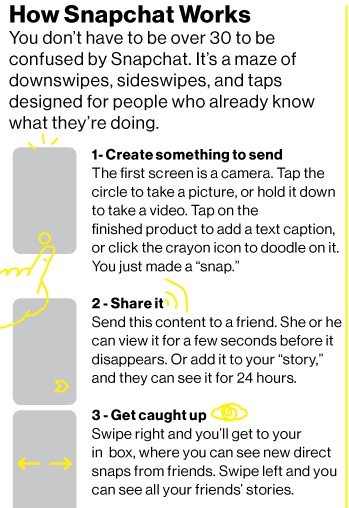

That second wave involved a shift from building the Internet to building on top of the Internet. The focus moved from connecting people to creating new ways for them to access information and one another. The sheer volume of information enabled Google to create a dominant search engine. Apple roared back to life with a vision of seamless integration of hardware, software and services. And the explosion in smartphones enabled the Internet to go mobile, unleashing the app economy.

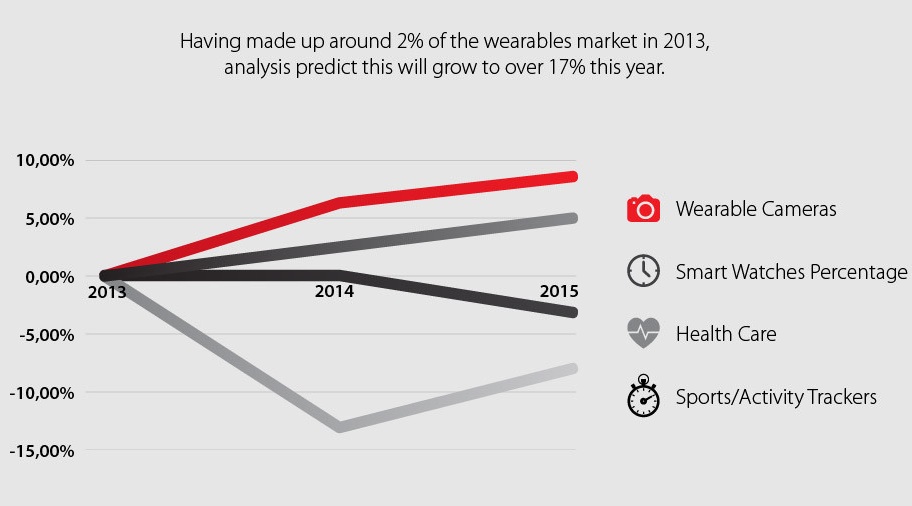

The third wave of the Internet is about to break. The opportunity is now shifting to integrating it into everyday life, in increasingly seamless and ubiquitous ways. These third-wave companies will take on some of the economy’s largest sectors: health care, education, transportation, energy, financial services, food and government services. These third-wave sectors — all now ripe for disruption — represent more than half of the U.S. economy.

To be successful during the third wave they will need to remember the three P’s:

Perseverance: Overcoming long-term structural changes within regulated sectors won’t happen overnight; entrepreneurs (and investors) will need to be more patient.

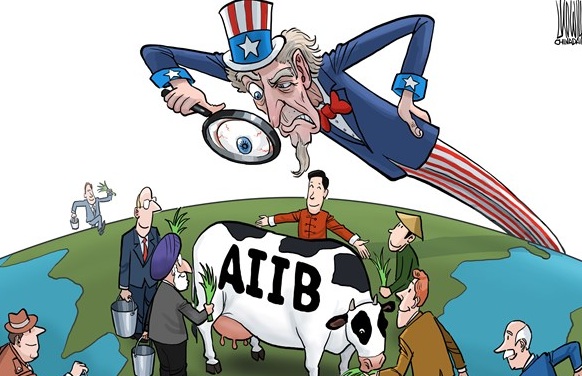

Partnerships: Just as partnerships were key in the first Internet wave, they will be key again in the third. Entrepreneurs won’t be able to go it alone in the third wave; they must go together.

Policy: Entrepreneurs will need to understand public policy in a more nuanced way. Last year, 75 percent of venture capital went to just three states: California, Massachusetts and New York. But 75 percent of our Fortune 500 companies are located in the 47 other states, and many of them will play a pivotal role in the third wave, as a new generation of partner-friendly entrepreneurs seeks strategic alliances to gain credibility and accelerate growth.