Luis A. Moreno: At the upcoming Summit of the Americas in Panama City, business and government leaders will discuss the economic challenges facing the Western Hemisphere, especially how to support inclusive growth in the wake of the commodities bonanza that endured for the better part of the last decade. Any strategy will have to account for an inescapable global phenomenon: the so-called “Second Machine Age.”

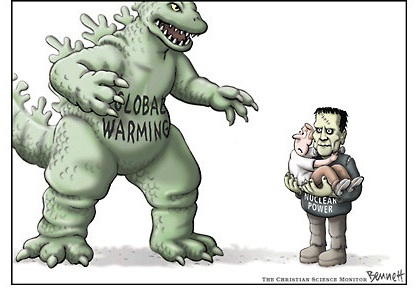

The MIT economists Andrew McAfee and Erik Brynjolfsson, among others, identify the Second Machine Age with the rise of new automation technologies and artificial intelligence. While optimists predict that these innovations will usher in an era of unprecedented abundance, less sanguine analysts estimate that nearly half of all jobs currently performed by humans are vulnerable to replacement by robots and increasingly sophisticated software.

Advanced technologies are already making inroads into some of Latin America’s principal industries. For example, carmakers, which employ hundreds of thousands of people across the region, are rapidly deploying robots that are more efficient and precise than humans. I

Service industries, which already account for two-thirds of all jobs in Latin America, are particularly vulnerable. One Brazilian startup’s tax-management software, for example, can perform in seconds operations that would demand thousands of billable hours from an army of accountants.

Is Latin America ready for this epochal change?

Most notably, Latin American and Caribbean economies must address their productivity gap – the result of their failure, with few exceptions, to boost productivity significantly since the 1960s. As they adjust to lower prices for oil, metals, and grain – and the eventual upturn in global interest rates – they will have to pursue productivity-enhancing reforms. Ensuring that the region’s already-skewed income distribution does not worsen – and, indeed, improves – is also essential.

The good news is that Latin America’s agendas for technology, productivity, and inclusivity overlap; for example, improvements in education and the encouragement of formal employment advance all three objectives.

First, companies can boost their own human capital by providing on-the-job training – a proven tactic that remains rare in Latin America. Here, there has been some progress.

Second, Latin American companies should increase their investment in research and development.

Latin American businesses can change this by emulating their counterparts in the Brazilian state of São Paulo, which have research contracts with leading public universities. Such links, common throughout North America, have helped to lift São Paulo’s R&D spending to 1.6% of GDP – higher than that of Spain or Italy.

Third, Latin American companies can help to improve education – often much faster than the government can implement effective reforms. In Peru, one businessman took matters into his own hands, commissioning the creation of an entirely new education model. Four years later, Carlos Rodriguez-Pastor has established 23 Innova schools, serving 13,500 students, where teachers’ knowledge and skills are continuously updated. He hopes to build a 200-school network in the coming years.

Finally, Latin American business leaders should support budding entrepreneurs, who lack not only the capital, but also the support system needed to turn their ideas into viable ventures.

Von Ahn, a professor at Carnegie Mellon University in the United States, has already sold one innovative company to Google. That company, reCAPTCHA, harnesses CAPTCHAs to have people decode a word from, say, a newspaper article that a computer scanner has been unable to recognize and digitize.

Latin America cannot afford to lose gifted innovators like von Ahn. It is in the interest of established business leaders to help mentor and finance these visionaries, enabling them to flourish at home so that they do not set up shop abroad.