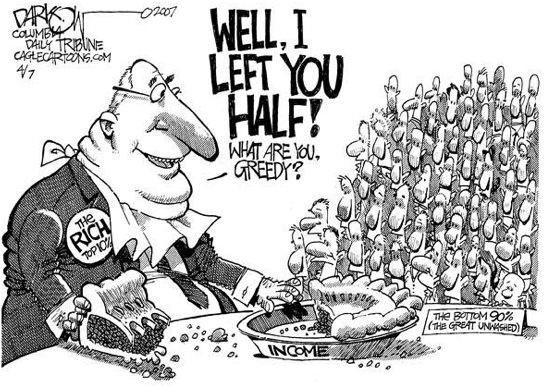

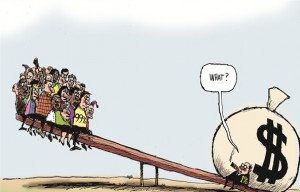

Making the reduction of income inequalities the sole focus of public policy — dubbed macreconomic populism — has been a recurring presence in Latin American economic history. At certain times over the past 40 years, it has been costly and traumatic, which is true today for Venezuela and Argentina.

This policy approach often overlooks internal restrictions such as the simultaneous need for sustainable fiscal balance, price stability and wage alignment based on productivity. There are also external limitations such as balancing trade and improving the country’s international credit rating, all hopefully within a framework of growth. And populism today has acquired an additional association with bad institutions that aggravate the problem of concentrated markets.

The populist cycle, which lives through three phases of varying duration, is often attributed to irrational voting motivated by an overwhelming faith in electoral promises that ignores potential long-term consequences. Others see the durability in populism in the unfortunate combination of unsatisfied social and political demands, as well as the absence of institutions that equitably distribute the benefits and burdens of society.

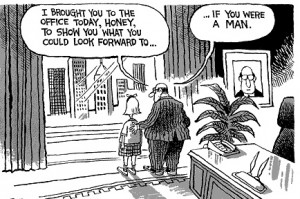

From 1990 to 2003, Argentina had a growth rate of just 2.1% of GDP, an unemployment rate of 14.6% and average inflation rate of 197%. Venezuela grew about 2.5% a year up until 1999, with unemployment at 10.1% and average inflation of about 46%. There was public dissatisfaction with economic performance in both countries. There were calls to redistribute incomes as part of reactivating and restructuring the economy, as successor regimes took power.

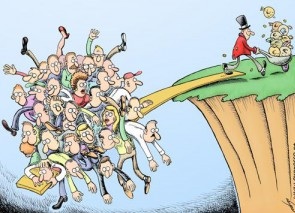

In the first part of that period between early 2000 and 2011, attending to the social clamor of both countries was the recurring theme that justified a relentless rise in public spending and “raids” into market territority by imposing price controls of various types. The public welcomed measures such as fossil fuel subsidies as high as 80%, taxes and restrictions on dollar trading, import/export quotas, and certain tax incentives and industry nationalization.

External conditions were favorable. Increasing Chinese demand from 2002 boosted energy and commodities prices during that period — soya 25%, cereals 49.5% and oil 103.5%. This gave the confused impression of impressive growth, with rates of 4.8% and 7.1% of GDP for Venezuela and Argentina, respectively.

But the bill for these policies inevitably arrives. A more than 40% fall in crude oil prices and about 20% for other raw materials has decimated the revenues of both countries. Growing unemployment, the end of protected jobs, food and consumer shortages, power cuts and ballooning debt are all symptoms announcing the coming, third phase of the populist cycle: crisis and collapse. The International Monetary Fund expects both economies to shrink about 2% in 2015, and the mid-term panorama is somber.

Evidence shows that macroeconomic populism is unstable macroeconomic despite advances in the “good years,” perhaps because of its exclusively short-term focus. Both these countries need institutions that will create credible and stable expectations that encourage investment, rather than promises that destroy what was built before them.