Dean Starkman writes: Anat R. Admati, a professor of finance and economics at Stanford’s business school, is an unlikely player in Washington’s financial reform scene.

The Israeli-born economist arrived at Stanford in 1983 with an interest in mainstream financial issues and a firm belief that markets—with their unique ability to assign a price to risk and channel capital to its most efficient use—were a powerful force for good.

The 2008 financial crisis upended that faith. She turned her gaze to the industry at the center of the crisis: banking.

Admati made waves on the national financial reform scene in 2013 with the book “The Bankers’ New Clothes: What’s Wrong With Banking and What to Do About It,” co-authored with economist and banking expert Martin Hellwig.

Here’s an excerpt of a discussion with Admati:

Why did you write “The Bankers’ New Clothes,” a book for the general public and not strictly for scholars?

We thought we had to. There was, I thought, a certain lack of engagement on the part of many academics, and it was disturbing to me that there was not enough serious discussion about what was going on.

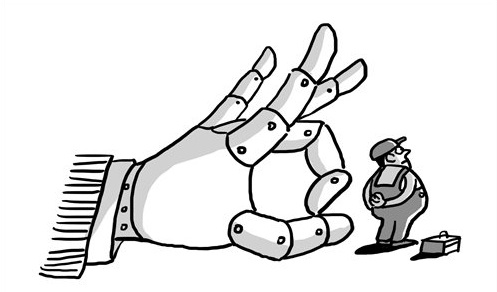

I was not a banking expert, but after studying it, I found that a lot of policymakers and people commenting on it didn’t actually know what they were saying or were saying wrong things or misleading things.

There seemed to be, to take a charitable interpretation, that there were blind spots or confusion or, the most cynical interpretation, there was sort of willful blindness.

How did you get so involved in Washington financial policy circles?

From the beginning, I tried very hard to engage with anybody in Washington who would engage with me. It started by being appointed by Sheila Bair (then the FDIC chairwoman) to a committee in the spring of 2011, which just allowed me into the room at all.

So, what’s wrong with banking?

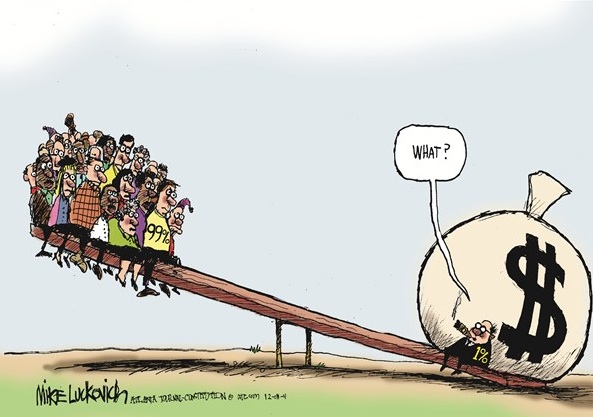

What’s wrong with banking is that a lot of people are able to take risks and not be fully responsible and accountable for those actions.

People need to understand that the biggest banks are really, really big, by any measure. Just how much is a trillion? It’s an enormous number. They are larger than just about any corporation, so it’s not just big. It’s really very, very big.

It’s also the complexity and sort of breathless scope of what they do and just how much of it is opaque. It remains incredibly fragile as a system.

Capital requirements, boiled down, amount to a few percentage points of a bank’s total assets. What’s the right ratio?

Current requirements are ridiculous by any normal standards. A supposedly “harsh” regulation would be 5 percent of the total. Corporations just never ever live like that.