Robert Rubin, Secretary of the Treasury and Nicholas Turner, head of a criminal ustie institute write on the problem of high incarceration rates in the US. They cite a comprehensive report published this year.

This is not only a serious humanitarian and social issue, but one with profound economic and fiscal consequences. In an increasingly competitive global economy, equipping Americans for the modern workforce is an economic imperative. Excessive incarceration harms productivity. People in prison are people who aren’t working. And without effective rehabilitation, many are ill-equipped to work after release.

Interestingly one person exploring a possible Presidential candidacy in 2016, former Senator Jim Webb of Virginia, has been trying to address this problem for a very long time. He first became interested in inarceration rates when he visited prisons in Japan, a country half our size with incarceration rates about 1/20th of ours.

He then tried to develop ths issue as he was campagining. When asked whether this was foolish for a US politician, whose popularity is usually determined by ‘tough on crime’ caveats, he said he felt a politican should lead on issues, not follow.

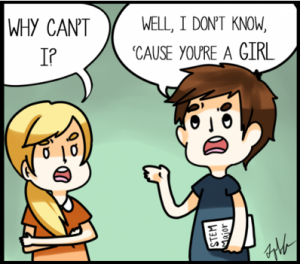

Clearly in the US our punishment of victimless crimes is out of control. Clearly also, the majority of people incarcerated are of African American descent.

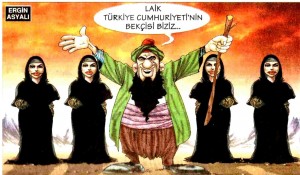

In addressing on a deeper level the cause of racial division in the US, we would do well to listen to Jim Webb.

Robert Rubin seldom bills as one his crednetials his position as a partner of Robert Freeman on the arbitrage desk of Goldman Sachs. Freeman was led out of Goldman in handcuffs for insider trading, although he ended up only pleaing to a mail fraud charge. He did spend 4 months in jail, a rare event for people of Freeman and Rubin’s ilk. Is Rubin’s recent interest a mea culpa or a way of lobbing an issue up in the air that is more apporpriately Jim Webb’s than Rubin’s good friend Mrs. Clinton’s.

Let’s hope that if this is poitics as usual that the issue sticks and begins to be addressed in the US.