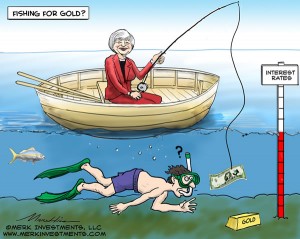

Is the US Fed making accurate assessments of its interest rate policies?

Barry Eichengreen writes: For much of the year, investors have been fixated on when the Fed will achieve “liftoff” – that is, when it will raise interest rates by 25 basis points, or 0.25%, as a first step toward normalizing monetary conditions. Markets have soared and plummeted in response to small changes in Fed statements perceived as affecting the likelihood that liftoff is imminent.

But, in seeking to gauge changes in US monetary conditions, investors have been looking in the wrong place. Since mid-August, when Chinese policymakers startled the markets by devaluing the renminbi by 2%, China’s official intervention in foreign-exchange markets has continued, in order to prevent the currency from falling further. The Chinese authorities have been selling foreign securities, mainly United States Treasury bonds, and buying up renminbi.

This is the opposite of what China did when the renminbi was strong. Back then, China bought US Treasury bonds to keep the currency from rising and eroding the competitiveness of Chinese exporters. As a result, it accumulated an astounding $4 trillion of foreign reserves.

And what was true of China was also true of other emerging-market countries receiving capital inflows. These countries’ foreign reserves, mainly held in US securities, topped $8 trillion at their peak last year.

The effects of these purchases attracted considerable attention. Although no one outside official Chinese circles knows the exact magnitude of China’s foreign-exchange intervention, informed guesses suggest that it has been running at roughly $100 billion a month since mid-August. Observers believe that roughly 60% of China’s liquid reserves are in US Treasury bills. Given that reserve managers prefer to avoid unbalancing their carefully composed portfolios, they probably have been selling Treasuries at a rate of roughly $60 billion a month.

The effects are analogous – but opposite – to those of quantitative easing. Menzie Chinn of the University of Wisconsin has examined the impact of foreign purchases and sales of US government securities on ten-year Treasury yields. His estimates imply that foreign sales at a rate of $60 billion per month raise yields by ten basis points. Given that China has been at it for 2.5 months, this implies that the equivalent of a 25-basis-point increase in interest rates has already been injected into the market.

Some would object that the renminbi is weak because China is experiencing capital outflows by private investors, and that some of this private money also flows into US financial markets. This is technically correct, but it is already factored into the changes in interest rates described above.

Another objection is that QE operates not just through the so-called portfolio channel – by changing the mix of securities in the market – but also through the expectations channel. It signals that the authorities are seriously committed to making the future different from the past. But if Chinese intervention is just a one-off event, and there are no expectations of it continuing, then this second channel shouldn’t be operative, and the impact will be smaller than that of QE.

The problem is that no one knows how long capital outflows from China will persist or how long the Chinese authorities will continue to intervene.