Do we need a new migration policy?

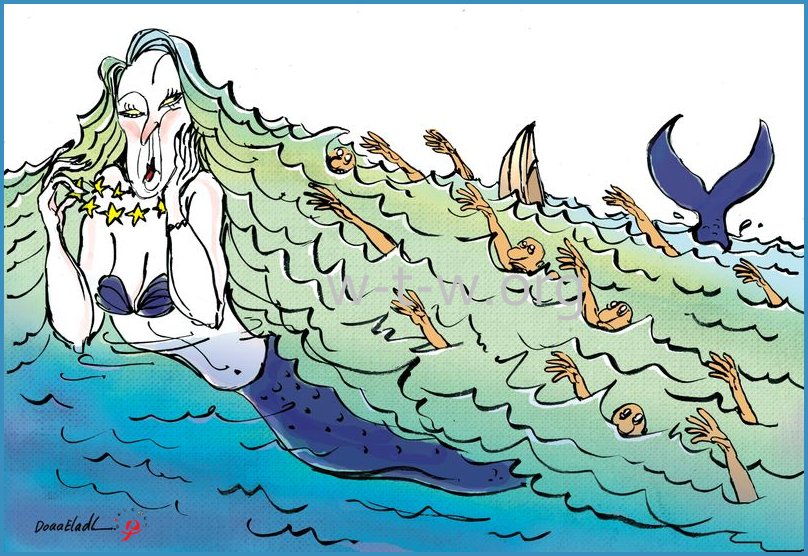

Jacqueline Bhabha writes: Our current asylum system allocates protection only once someone has made it to the border of a safe country. Vigorous, generous, and transparent resettlement programs that preemptively move victims of conflict from refugee camps or informal settlements in adjacent countries to destination states are the most effective and humane way to address this undisputed need for protection.

Acknowledging up front that hundreds of thousands of people urgently need to relocate in the face of a conflict like the Syrian war, and creating a system for managing this reality, requires powerful leadership and a vigorous partnership among civil society, progressive municipal authorities, and federal and regional bodies.

First, in addition to much more generous resettlement of distress migrants, we need more capacious categories for legal migration—for family reunification, for education and skill-training visas, for work permits and for opportunities for entrepreneurs, small and large, to access places of safety and contribute to their economies from a position of confidence and strength rather than as destitute supplicants.

Second, high-quality, well-funded systems need to be put in place for the most vulnerable: survivors of trafficking, children separated from their families, and migrants with urgent health needs (physical or psychological).

Finally, and most critically urgent, making borders more permeable, not less, will ensure that people can come and go with more ease, moving to safety when they need to but returning home when this seems feasible, without the current fear that a decision to return home is irrevocable.

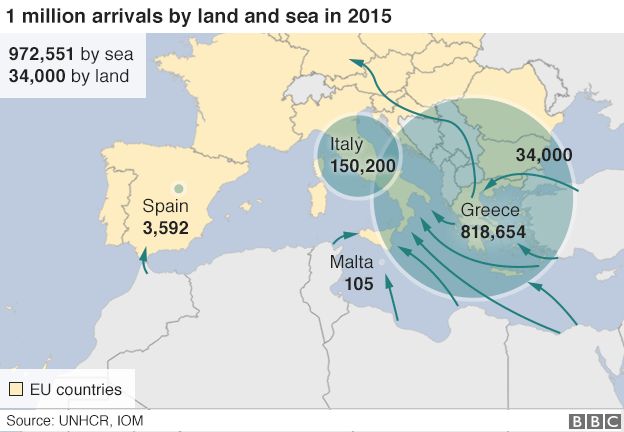

Without energetic steps to institute these changes, the prospects for the coming winter, and beyond, are indeed grim. Migration- By Land and By Sea