The relationship between manufacturing, development in emerging nations and ‘growth’ in developed ones is a challenging issue.

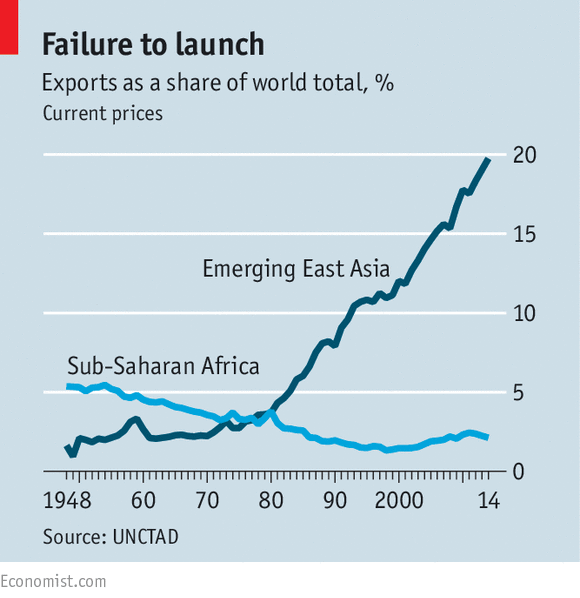

From the Economist: Over the past 15 years sub-Saharan African economies have expanded at an average rate of about 5% a year, enough to have doubled output over the period. They were helped largely by a commodities boom that was caused, in part, by rapid urbanisation in China. As China’s economy has slowed, the prices of many commodities mined in Africa have slumped again. Copper, for instance, now sells for about half as much as it did at its peak. This, in turn, is hitting Africa’s growth: the IMF reckons it will slip to under 4% this year, leading many to fret that a harmful old pattern of commodity-driven boom and bust in Africa is about to repeat itself. One of the main reasons to worry is that Africa’s manufacturing industry has largely missed out on the boom.

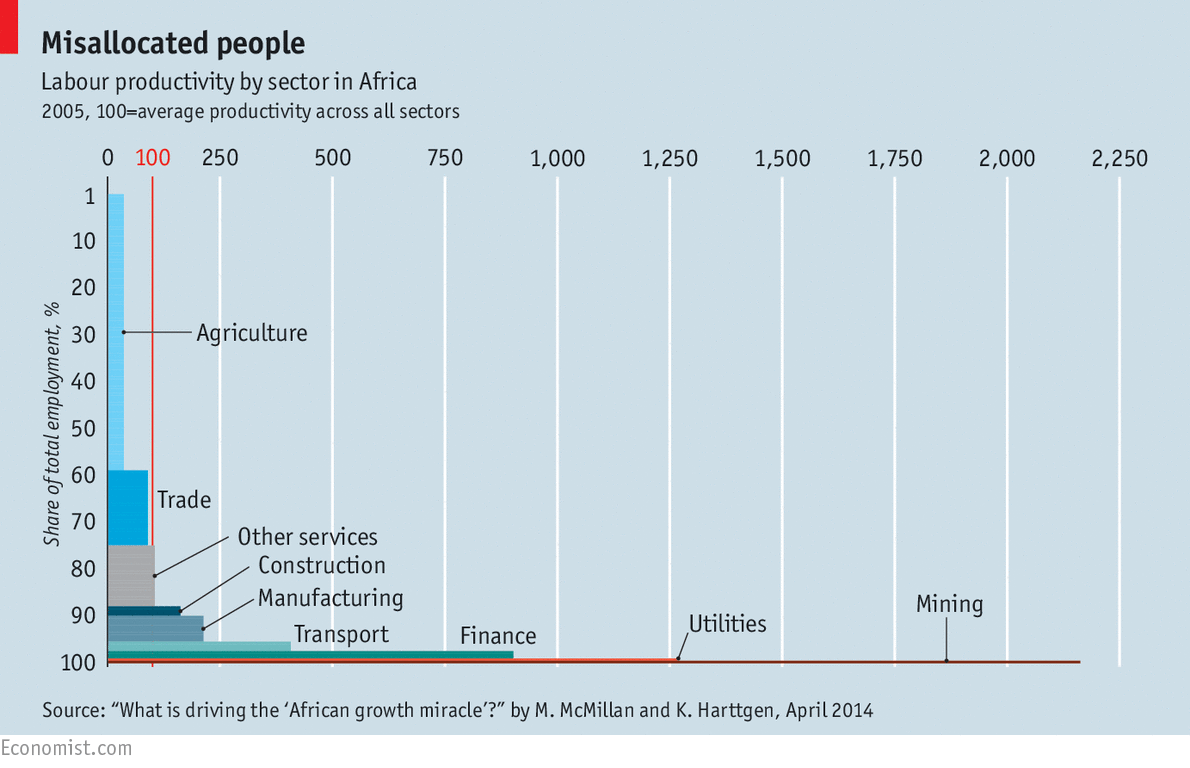

The figures are stark. The UN’s Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA), which is publishing a big report on industrialization in Africa next month, reckons that from 1980 to 2013 the African manufacturing sector’s contribution to the continent’s total economy actually declined from 12% to 11%, leaving it with the smallest share of any developing region. Moreover, in most countries in sub-Saharan Africa, manufacturing’s share of output has fallen during the past 25 years. A comparison of Africa and Asia is striking. In Africa manufacturing provides just over 6% of all jobs, a figure that barely changed over more than three decades to 2008. In Asia the figure grew from 11% to 16% over the same period.

Many countries deindustrialize as they grow richer (growth in service-based parts of the economy, such as entertainment, helps shrink manufacturing’s slice of the total). But many African countries are deindustrializing while they are still poor, raising the worrying prospect that they will miss out on the chance to grow rich by shifting workers from farms to higher-paying factory jobs.

Premature deindustrialisation is not just happening in Africa—other developing countries are also seeing the growth of factories slowing, partly because technology is reducing the demand for low-skilled workers. Manufacturing has become less labor intensive across the board.

Yet deindustrialization appears to be hitting African countries particularly hard. This is partly because weak infrastructure drives up the costs of making things.

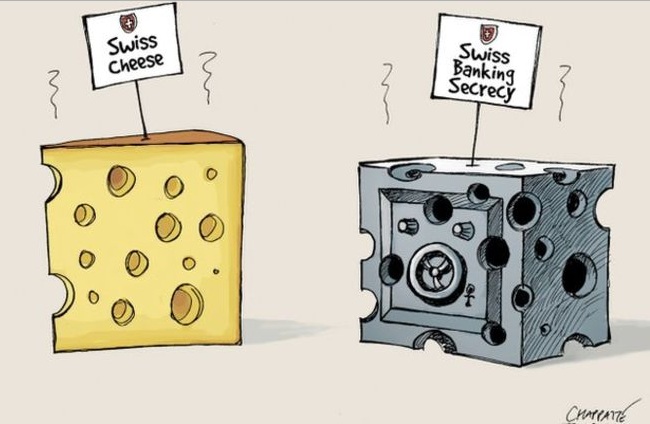

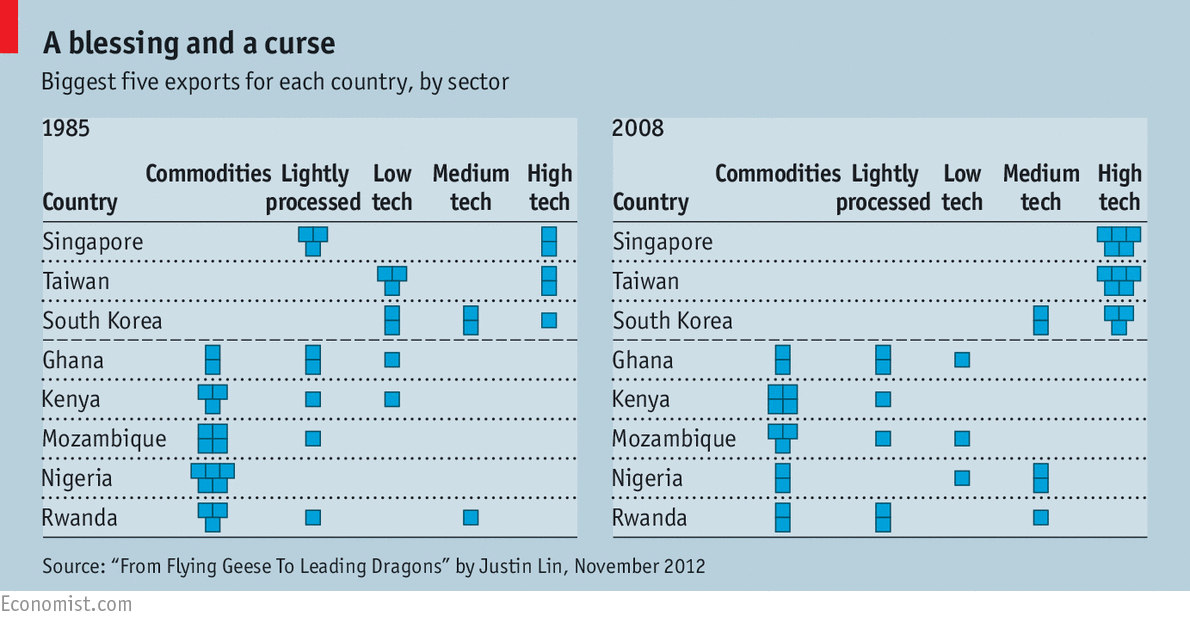

Africa’s second disadvantage is its bounty of natural riches. Booming commodity prices over the past decade brought with them the “Dutch disease”: economies benefiting from increased exports of oil and the like tend to see their exchange rates driven up, which then makes it cheaper to import goods such as cars and fridges, and harder to produce and export locally manufactured goods.

Africa’s final snag is its geography. East Asia’s string of successes happened under the “flying geese” model of development, where a “lead” country creates a slipstream for others to follow. This happened first in the 1970s, when Japan moved labour-intensive manufacturing to Taiwan and South Korea. But Africa seems to have missed the flock.

Ethiopia has bucked this trend. Tanzania, where manufacturing output has grown 7.5% annually from 1997-2012, is wooing Chinese and Singaporean clothing firms and started building its first megaport and industrial park last month. Rwanda has attracted investment from Helen Ai, the woman behind Ethiopia’s most successful shoe firm. Her garment factory plans to hire 1,000 workers by the end of the year.

Nonetheless, factories are not creating nearly enough jobs for the millions of young people moving into cities each year. Most of them end up in part-time employment in low-productivity businesses such as groceries or restaurants, which are limited by the tiny domestic economy; Africa generates only 2% of the world’s demand. To grow fast, African countries need to shift workers into more productive industries. Their governments need to provide the infrastructure and the incentives for manufacturing firms to set up. Without determined action, they risk another lost decade as the commodity bust deepens.