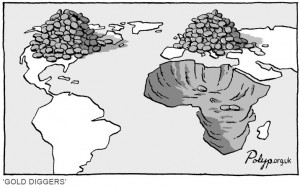

Acha Leke and Michael Katz write: A paradox of Sub-Saharan Africa’s rapid economic expansion is the fact that the region’s most sophisticated economy seems not to be part of it. Since 2008, South Africa has recorded average annual GDP growth of just 1.8%, less than half the rate of the previous five years. Sub-Saharan Africa is porjected to grow at a rate of close to 5% next year, but South Africa is projected at about 1% growth. More worrying still, the country’s 25% unemployment rate is one of the highest in the world.

Countries across the continent are constructing the roads, ports, power stations, schools, and hospitals. They need to sustain their growth and meet the needs of their fast-growing and urbanizing populations. They need most of all is expertise.

But while South Africa has highly capable architecture, construction, and engineering sectors, its current share of foreign-built projects in Sub-Saharan Africa stands at only 7%, compared to 32% for China.

The opportunities are not limited to the construction industry. South Africa has the know-how to meet Africa’s burgeoning need for a wide range of services, from banking and insurance to retail and transport. The country currently provides only 2% of Sub-Saharan Africa’s service imports – a market worth some $40 billion annually.

South Africa is home to several well-established, innovative banks that are well placed to offer low-cost, digital services to millions of currently unbanked African households and businesses. Indeed, South African banks already command a 12% share of Sub-Saharan Africa’s banking market.

South Africa has a highly developed insurance sector, with a long history of creating products for every demographic and income level. It is ideally placed to provide insurance to the rest of Sub-Saharan Africa, where just 1% of households have insurance of any kind.

South Africa also has been punching below its weight in merchandise trade.

The key to reigniting South Africa’s economic growth is an ambitious regional strategy driven by government and business leaders working in partnership. A massive scale-up of vocational education is particularly important, as this will provide young South Africans with the technical skills needed to support the expansion of export industries. Putting in place infrastructure to support growth – notably power generation, which currently lags demand – will also be crucial.

South Africa’s economic transformation since its transition to democracy two decades ago has been remarkable. But its renaissance is in danger of running out of steam. Only by boldly seizing the initiative can South Africa put itself at the core of Africa’s economic renewal, and only by embracing its role as regional leader can it revitalize its own prospects.