Alan S. Blinder wrote “What’s the Matter with Eoonomics?” Blinder concludes that except for some right-wingers outside the “mainstream” and politicians’ refusal to accept economists’ recommendations, little is the matter. However, economists’ thinking, based on an ill-conceived view of human behavior and addressed to the wrong problem, is a powerful force in policy circles.

Blinder’s textbook, written with William Baumol, is the standard for the mainstream. Both are extraordinarily good economists, liberal and not doctrinaire.

Economists, however, have been unable to forecast accurately based on the exposition put forth iby Blinder. For example, the Federal Reserve Board’s belief in (mostly) efficient markets led to it missing the signs of the Great Recession; as late as June 2006 the Fed raised interest rates fearing that “some inflation risks remain.” For years, the Fed had rejected board member Ned Gramlich’s warnings that the practices of subprime lenders were not consistent with the assumptions of the Fed’s economists. Mainstream economists did not predict the effects of eliminating Glass-Steagall, thereby allowing large banks to design and sell the products that helped bring about the collapse.

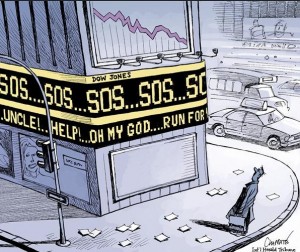

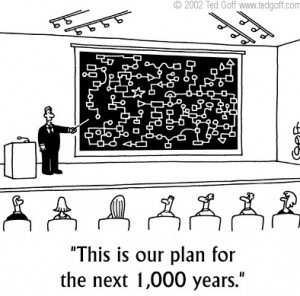

Although recognizing that markets can be flawed, Blinder states that minimum waste “can be achieved extraordinarily well by letting markets operate more or less freely” and that market methods can remedy the few flaws in the market. The role of economists is removing barriers to the markets’ efficient allocation of usually scarce resources (they assume full employment). For the perhaps 200 million unemployed worldwide the more important issue, however, is the chronic underemployment of potential resources. Economists do not build the distribution of income into their models; but 80 percent of the world population lives on less than $10 a day, which surely wastes substantial human resources. A reexamination of the efficiency of markets, especially financial markets, is in order.

More is wrong with economics than a few right wingers. Mainstream economists claimed until the eve of the 2008 catastrophe that they had at last learned how to manage the economy well. This was quite an error of analysis and thinking, and did not principally come from the right. The leaders of this mainstream analysis were centrist Ben Bernanke, the former Federal Reserve chairman, and moderate liberal Olivier Blanchard, chief economist of the International Monetary Fund.

They argued that the stability of the GDP since the 1980s was an indication that the problem of macroeconomic adjustment had been solved. Stability is fine, but over this period debt soared, growth slowed on average, wages stagnated or fell, inequality rose, and there were at least seven American financial crises. Then came disaster in 2008. What were they talking about?

Did policymakers listen to these ideas? They still do at the Federal Reserve, where foolish bickering over whether inflation will reach 2 percent a year still goes on. Stale, discarded ideas? Hardly.

Say’s Law, an argument for austerity economics and a self-adjusting economy, was defeated by the Depression. Blinder cites a survey showing that most economists agreed that the Obama stimulus was effective. Sure, after the sharpest drop in GDP since the Great Depression. As some facetiously put it, we are all Keynesians in a foxhole.

“The ideas of economists and political philosophers, both when they are right and when they are wrong, are more powerful than is commonly understood,” wrote John Maynard Keynes in 1936. “It is ideas, not vested interests, which are dangerous for good or evil.”

Does economics explains growth better than other disciplines? Iit reflects the typically narrow focus of a top mainstream economist. Sociology and political history are critical to understanding Chinese economic development, for example. The recently famous Hyman Minsky, who is now cited constantly for his work on speculative bubbles, was more sociologist and psychologist than technical economist.

Even today, seventy-eight years after Keynes taught the world how to end recessions, many politicians in many countries refuse to follow his (now very mainstream) advice. That’s not a good show for“a powerful force in policy circles.”