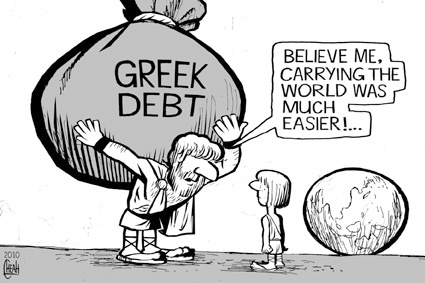

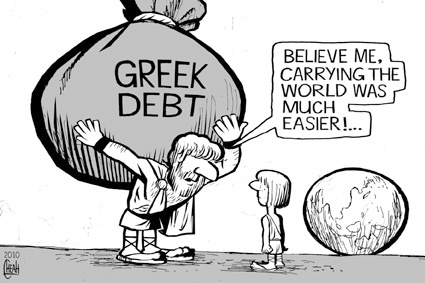

Dambisa Moya writes: The ongoing Greek debt saga is tragic for many reasons, not least among them the fact that the country’s relationship with its creditors is reminiscent of that between the developing world and the aid industry. Indeed, the succession of bailouts for Greece embodies many of the same pathologies that for decades have pervaded the development agenda – including long-term political consequences that both the financial markets and the Greek people have thus far failed to grasp.

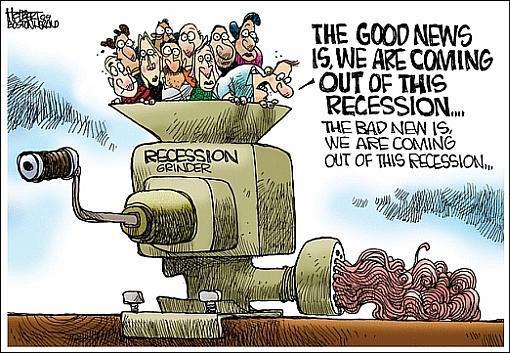

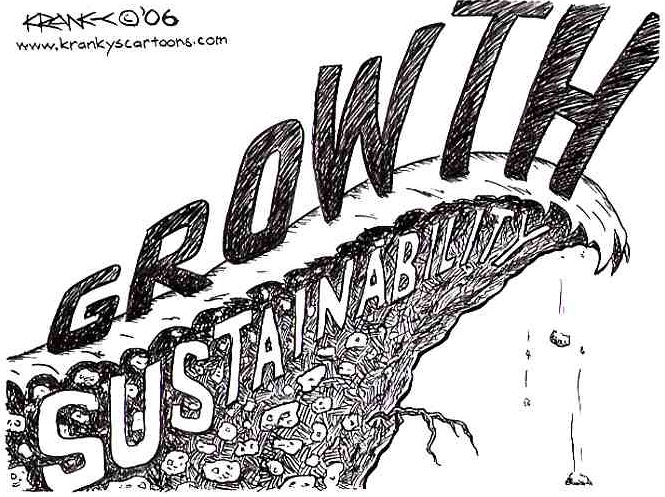

As in the case of other aid programs, the equivalent of hundreds of billions of dollars has been transferred from richer economies to a much poorer one, with negative, if unintended, consequences. The rescue program designed to keep Greece from crashing out of the eurozone has raised the country’s debt-to-GDP ratio from 130% at the start of the crisis in 2009 to more than 170% today, with the International Monetary Fund predicting that the debt burden could reach 200% of GDP in the next two years. This out-of-control debt spiral threatens to flatten the country’s growth trajectory and worsen employment prospects.

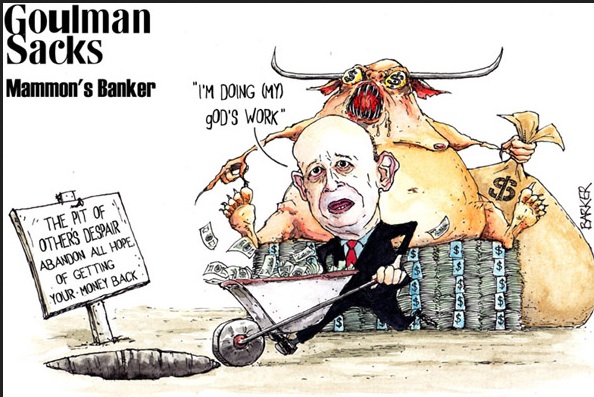

Like other aid recipients, Greece has become locked in a codependent relationship with its creditors, which are providing assistance in the form of de facto debt relief through subsidized loans and deferred interest payments. No reasonable person expects Greece ever to be able to pay off its debts, but the country has become trapped in a seemingly endless cycle of payments and bailouts – making it dependent on its donors for its very survival.

The country’s creditors, for their part, have an incentive to protect the euro and limit the geopolitical risk of a Greek exit from the eurozone. As a result, even when Greece fails to comply with its creditors’ demands – for, say, tax hikes or pension reforms – it continues to receive assistance with few penalties. Perversely, the worse the country performs economically, the more aid it receives.

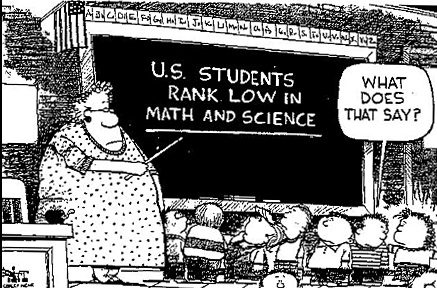

The long-term consequences of this cycle of dependence could be serious. As long as Greece’s finances are propped up by international creditors, the country’s policymakers will be able to abdicate their responsibility to manage the provision of public goods like education, health care, national security, and infrastructure. They will also face few incentives to put in place a properly functioning system to collect taxes.

Dependence on aid undermines the implicit contract between citizens and their government, according to which politicians must keep taxpayers satisfied in order to stay in office. With foreign infusions of cash easing the need for tax revenues, politicians are likely to spend more time courting donors than caring for their constituents.

The weakened connection between public services and taxes not only makes it easier for officials to cling to power, but also increases the scope for corruption and inefficiency. Indeed, based on the experience of aid-recipient economies in the emerging world, the Greek people may find it increasingly difficult to hold their government accountable or penalize officials for misbehavior or corruption.

So far, the Greek crisis has been treated as a recurring emergency, rather than the structural problem that it is. And yet, as long as the country remains locked in a cycle of codependence with its creditors, the state of perpetual crisis is likely to persist.

Effective aid programs have almost always been temporary in nature, working – as was the case with the Marshall Plan – through short, sharp, finite interventions. Open-ended commitments, like aid flows to poor developing countries, have had only limited success, at best. As long as Greeks view assistance as guaranteed, they will have little incentive to put their country on a path toward self-sufficiency. Whatever the way forward for Greece, if there is to be any hope of progress, the assistance provided by the European Union and the IMF must come to be regarded as temporary.

Cutting the umbilical cord in a relationship of aid dependency is never easy, and there is no reason to expect that it will be any different with Greece. Phasing out transfers, even in a considered and systematic way, works only when the recipient is determined to put in place the measures necessary to survive without assistance. There are few signs that Greece is ready to walk on its own, and as long as the aid continues to flow, that is unlikely to change. In this sense, markets should view the Greek situation as an equilibrium, not a transition.