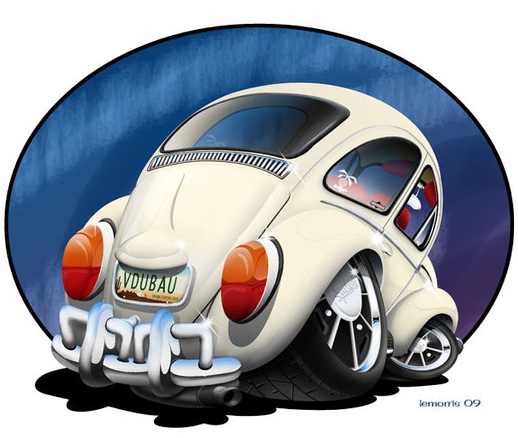

Can VW survive emissions manipulation scandal?

Volkswagen AG’s designated Chairman Hans Dieter Poetsch warned managers that the diesel-emissions scandal could pose “an existence-threatening crisis for the company.”

The German carmaker faces a Wednesday deadline to present a plan to fix some 2.8 million vehicles in its home market.

Volkswagen and German industry have been rocked by charges, first made by U.S. regulators on Sept. 18, that the carmaker had used software to hoodwink regulators about the true emissions of its diesel cars for years. As owners of 11 million affected cars across the globe, regulators and investors await answers, the crisis has wiped out almost 30 billion euros ($34 billion) of the company’s value.

After mostly remaining silent on the cheating scandal, ChancellorAngela Merkel on Sunday called the disclosure by Germany’s largest carmaker “a dramatic event” and said Volkswagen must clarify the affair swiftly. She ruled out a longer-term impact on the country’s industry.

An internal investigation has already yielded several engineers who admitted to installing the fraudulent software in 2008 for EA 189 diesel-motor models. The result was a so-called defeat device that disengaged emissions controls when an auto wasn’t being tested, breaching emissions rules and prompting a raft of government investigations and lawsuits since the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency cited the violations last month.

Volkswagen has also found more executives are involved in the scandal than previously acknowledged.

The manipulated software may have been put into parts supplied by Hanover, Germany-based Continental AG for 1.6-liter engines. Upgrading models with Continental parts would entail replacement parts, not just a software upgrade, Bild said.

Another engine-parts supplier, Robert Bosch GmbH, warned VW in 2007 that its planned use of the software was illegal.

In contrast with Merkel, European Parliament President Martin Schulz, a German Social Democrat, said the scandal is a “grave blow for the German economy as a whole.”