Three U.S. Democratic senators – Elizabeth Warren, Jeanne Shaheen and Richard Durbin have underscored the importance of Ukraine’s fight against corruption.

“When it comes to the issue of Ukraine there is unity between Democrats and Republicans, the Administration and Congress,” Durbin said. Then, referring to the EuroMaidan Revolution that sent Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych fleeing last year, the senator said: “We are in solidarity with Ukraine in terms of rebuilding this nation and protecting it from the invasion of the Russians. The spirit of Maidan lives on in terms of reform and change, which was the message of Maidan.”

President Petro Poroshenko and Prime Minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk are received “warmly” in Washington, D.C., while skepticism against the nation’s leaders is growing at home. Durbin said that the leaders have made “real progress” in such areas as energy and reforms.

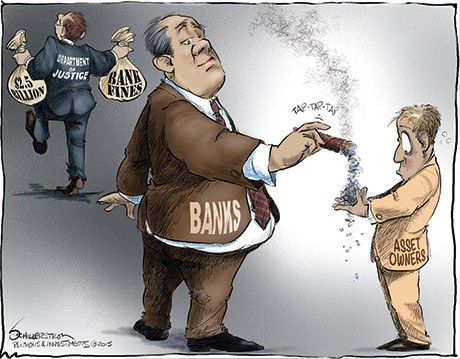

But corruption in Ukraine is an impediment to better U.S.-Ukraine relations.

“The jury is still out, the questions are still being asked,about real reform when it comes to corruption,” Durbin said. “The people of Ukraine are still looking for modernization and reform when it comes to this issue.”

Warren (Democrat of Massachusetts) said legal reform in Ukraine is essential.

“With weak rule of law, with a system rife with corruption, with a judiciary that is not independent and reliable, it is very difficult to build an economy going forward,” Warren said. A former law professor at Harvard Law School, Warren said that reducing corruption should be a priority in Ukraine.

“The support for this government from within the country and from without depends on real progress toward rooting out corruption,” Warren said. “Many countries around the world had to deal with the issue of corruption and it’s time for a best practices approach here,” Warren said. “It is time to try all measures, as vigorously as possible. And that is for two reasons: one is because some of them won’t be effective, the second is because the government must demonstrate in a very public way that it is committed to rooting out corruption no matter how painful, no matter how difficult.”

Warren said that, while reform is hard, “I also recognize from my time here that the people of Ukraine want reform, that the economy requires reform and that the U.S.A. will stand strong with those who fight for reform.

Durbin, whose state of Illinois has had many public officials who went to prison because of corruption, said that prosecution of lawbreaking politicians is essential.

“In the state of Illinois we have had our share of public corruption,” Durbin said. “We have responded to it by indicting, prosecuting and incarcerating those responsible.”

The U.S. will stand behind Ukraine as long as the dedication to fight corruption is “very clear,” the Illinois senator said.

Shaheen (Democrat of New Hampshire) said that Ukrainians must stop tolerating corruption.

“It’s about how members of the public deal with corruption,” Shaheen said. “Corruption exists everywhere, but if we refuse to tolerate it, then it’s going to be hard to continue to exist.”

Warren said that bringing rule of law will instill confidence in Ukraine’s government.

“Do not give up, this is a very hard fight,” Warren said. “If it were an easy fight, we would have already won…ultimately you will make the government work for you and not the reverse.”