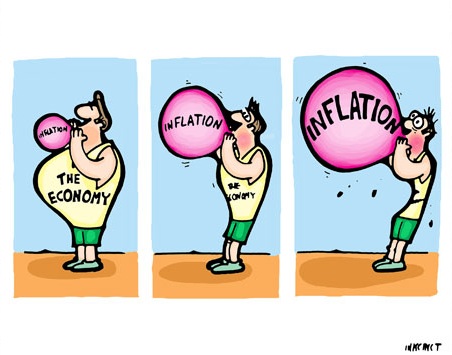

Jonathan Hill writes: Europe needs stronger, deeper capital markets. Our economy is about the same size as America’s, but our equity markets are less than half the size of theirs — and our debt markets less than one-third.

In the US, small and medium-sized companies raise about five times as much funding from capital markets as in the EU. If European venture capital markets were as deep as those in the US, our companies could have raised an extra €90bn over the past five years. And the differences between EU countries are even bigger than those between Europe and the US.

The benefits of stronger capital markets are also clear. We could give Europe’s businesses more choices over funding, helping them to invest and grow; increase investment in infrastructure; draw in more funding from outside the EU; help businesses sell into bigger markets; and help those saving for their old age. And, by reducing reliance on bank funding, we could help make the financial system more resilient, particularly in the eurozone.

All 28 members of the EU share this view. So does the European Parliament.

Some of the big questions are longstanding. How will we encourage investors to make cross-border investments when national insolvency laws are so different? How can investors gain access to comparable credit information on SMEs? How do we overcome national barriers, such as “passporting fees” if businesses operate in multiple countries?

Here are some clear priorities for early action.

To help free up banks’ balance sheets, making it easier for them to increase lending, I am proposing a new EU framework, with lower capital requirements, to encourage simple, transparent and standardized securitization. We need to make it more attractive to invest in infrastructure. A new infrastructure asset class that will attract lower capital requirements under the Solvency II regime for insurers.

Start-ups in need of capital should not be forced to go to the US, so I propose measures — including changes to legislation — to encourage the European venture capital scene to thrive. We need to make it easier for companies to raise funds on the public markets, too.

To channel more investment from Europe’s citizens to its businesses, we need to improve retail financial services. This means looking at them from the consumer’s point of view.

The creation of a capital markets union is a big opportunity for Europe. The UK, as Europe’s leading financial services centre, has a major contribution to make.

This is a good example of the practical benefits that membership of the single market can bring. But to make the most of it, and to help influence the rules which will set the terms of engagement for years to come, the UK needs to be shaping the system — not looking on while others set the rules.