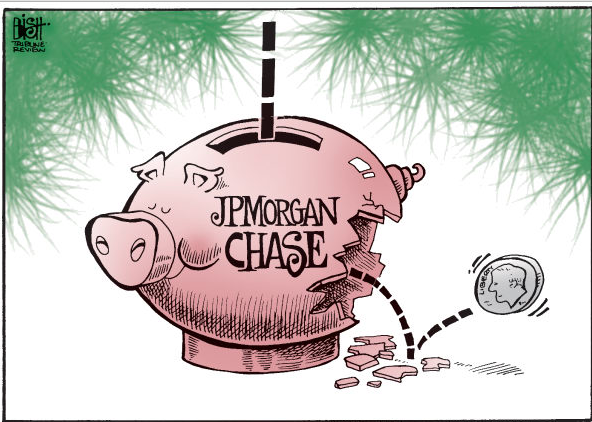

Glenn Reynolds writes: The financial crisis of 2008-09 is over but not gone. We passed laws and regulations that probably won’t help much. And despite a lot of harsh words aimed at Wall Street and the banks, President Obama pretty much let individual bankers escape unscathed — perhaps because Wall Street and the banks were among his biggest campaign contributors. (That phenomenon has led some to call him “President Goldman Sachs.”)

But relying on regulators to control banks and Wall Street is likely to fail anyway. Leaving aside their extensive political influence, financial types are likely to stay ahead of regulators because 1) they’re usually smarter; and 2) they understand their industry better. Plus, they can change approaches faster than regulators can amend regulations.

Even so, the apparent change in the financial community over the past few decades has been dramatic. The economic crisis brought the activities of investment bankers into the limelight, and suddenly it seemed the staid buttoned-up banker types of the popular imagination had been transformed into wild speculators risking billions on a single trade. What happened?

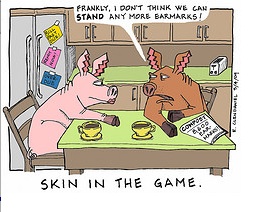

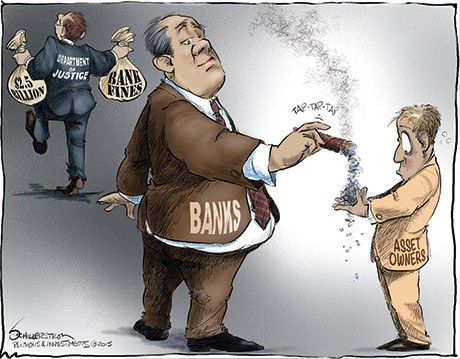

According to Claire Hill and Richard Painter in their new book, Better Bankers, Better Banks:Promoting Good Business through Contractual Commitment, the reason is that the billions they’re risking on a single trade aren’t their own but somebody else’s. Hill and Painter want to do something about it by requiring that financial operators have their own assets at stake.

This isn’t a new idea. Until fairly recently, big investment banks such as Goldman Sachs or Salomon Bros. operated as general partnerships. In a general partnership, the partners are liable — individually — for debts of the firm. With potentially unlimited liability if things went wrong, the partners had an incentive to be comparatively cautious. (With corporations, on the other hand, shareholders aren’t on the hook for the firm’s debts. The most they can lose is the value of their shares.) Without unlimited liability, incentives are different. As Hill and Painter note, Salomon’s culture changed very rapidly after it became a corporate entity in which the partners, now called “managing directors,” weren’t personally at risk. Within a few years it went from a staid, conservative business to the anything-goes entity described in Michael Lewis’ Liar’s Poker.

It’s easy to engage in risky schemes when success gets you a huge bonus, while failure just costs someone else some money. One solution would be to require investment banks to be organized as general partnerships.

Hill and Painter suggest “covenant banking,” in which bankers’ compensation is at risk for bad deals. Not only would they get bonuses when things go well, but they’d have to cough up past bonuses, and salary, when deals go badly for clients.

Such an approach might be required by law, but Hill and Painter think that banks might want to do it voluntarily. As a client, wouldn’t you rather deal with a banker who stands to lose money if you do? Shareholders might even demand that their companies do business with such banks, as a way of hedging against risk. Wouldn’t it be safer to do business with people whose incentives align with your goals? (I always say I’d like my life insurance company to be in charge of my health care because it would cost them a lot of money if I died; my actual health care company, on the other hand, might save money if I kicked off quickly.)

Many of our problems come from having people in charge who don’t feel the pain when their various schemes go bad. As a theme for the coming decade, we could do a lot worse than requiring skin in the game.