Are whistleblowers protected in the US?

U.S. Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., and Republican Chuck Grassley, of Iowa, urged the Securities and Exchange Commission this week for an update on the performance of so-called “whistleblower” protections created under the Dodd-Frank Act.

Warren and Grassley, in a letter to SEC Chair Mary Jo White, requested information on the agency’s Office of the Whistleblower, as well as asked about implementation of 2013 SEC Office of Inspector General recommendations, among other things.

According to Warren’s office, a 2013 OIG report regarding the implementation of protections created under the law, recommended that the Office of the Whistleblower establish standardized performance criteria for whistleblower complaints.

“The whistleblower program is an important tool in the SEC’s efforts to combat securities fraud and almost three years have passed since the SEC OIG evaluation of this program,” the senators stated in their letter. “We are writing to seek an update on the program’s performance and on OWB’s progress in implementing the OIG recommendations.”

Warren and Grassley urged the SEC chair to provide answers to several questions by Nov. 26, including: a description of progress in implementing the 2013 recommendations; the number of whistleblower tips, complaints and referrals received from July 2013 to June 2015; and the average time it took the office to review them upon receipt.

The senators also requested information regarding the average amount of time between posting a Notice of Covered Action and contacting the relevant whistleblower and the percentage of tips, complaints and referrals under investigation, among other data.

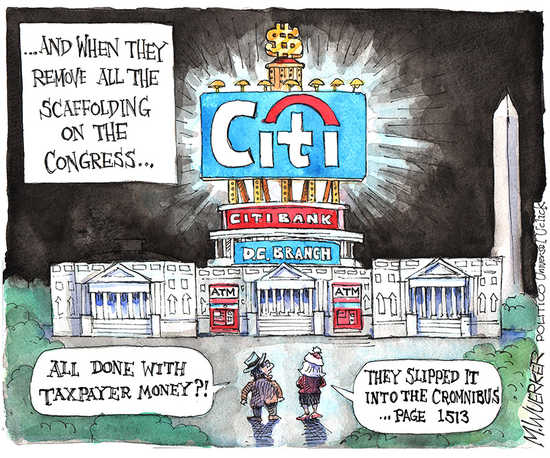

Under Dodd-Frank Congress expanded protections afforded to whistleblowers and provided incentives for reporting potential SEC violations, Warren’s office said. Two key provisions included in the law to expand whistleblower participation provided the SEC the authority to award cash payments to those who provide actionable tips and instructed the agency to create a new division to oversee the whistleblower program.

Warren’s letter came a week after the Democratic senator called on the SEC and Commodity Futures Trading Commission to implement rules that protect taxpayers and the financial system following Dodd-Frank changes.