Mark Roe writes: At a closed-door conference attended by senior bankers, regulators, and some academics, Federal Reserve Governor Daniel Tarullo and Federal Reserve Bank of New York President William Dudley used their bully pulpit to do something unexpected. Instead of focusing on how to bolster bank stability – channeling more capital toward the largest institutions, curbing their riskiest activities, and determining how to manage a failing bank without bailing it out – the officials discussed the bankers themselves.

Tarullo focused on managerial misbehavior, arguing that managers who do not comply fully and willingly with regulations should face tougher sanctions than they do now. Instead of blaming “a few bad apples” for wrongdoing, he insisted, institutions should implement controls that prevent “bad apples” from poisoning the organization. To this end, organizations should embed respect for law, regulation, and the public trust in internal compensation systems.

Moreover, Tarullo cited criminal prosecution and imprisonment of individuals as the most effective way to deter illegal conduct, such as breaches of antitrust law. Of course, as he acknowledged, prosecuting an individual for such violations is difficult, because regulators lack criminal enforcement powers, evidentiary hurdles are high, and the circumstances are often uncertain. But regulators have not taken enough advantage of the authority that they do have to punish errant managers: they can ban these individuals from working in finance.

According to Tarullo, a few well-chosen “bans from banking” could change the financial industry for the better. He urged bank boards and senior executives to preempt such bans by firing highly problematic managers publicly, rather than sending them quietly out the back door. Public executions would deter the rest of the organization from bad behavior.

Dudley also placed the onus for change on senior bank managers. In discussing bank culture – a major topic of interest for him and the New York Fed – he encouraged senior bankers to align their organizations’ cultures with the public interest and regulatory parameters. Instead of viewing the law as a problem to manage and, if possible, evade, bankers should recognize and respect its vital importance (a point that Tarullo also made). In this sense, Dudley said, the banking industry “is not close to where it needs to be.”

Like Tarullo, Dudley stressed that violations should not be treated as isolated actions by deviant employees, but as evidence of failure by senior managers – from the boardroom to the executive suite – to orient bank culture properly. Violations should thus catalyze a concerted effort by senior managers to bring so-called rogue bankers under control and to infuse their organizations with an ethos of compliance and integrity. If they are unable to do so, Dudley argued, a reasonable conclusion would be that the organization is too big to manage.

For at least a few listeners, this statement probably evoked memories of the trader known as the “London Whale,” who lost at least $6 billion at JP Morgan Chase – America’s largest bank – in 2012. The bank’s risk-management team, reputedly the best in the world, failed to identify a rogue trader in their midst until it was too late.

The focus on individuals’ responsibility within banks represents a notable change in regulators’ approach, and it was reinforced by a third initiative, which other speakers emphasized: using deferred debt-based compensation to tie managers’ pay to bank safety and soundness.

Catalyzing a shift in bank culture will not be easy. Bankers know that assuming substantial amounts of low-probability, high-impact risk often benefits bank shareholders and bolsters their own bonuses. But, when things go wrong, the government picks up much of the bill – and the real economy suffers.

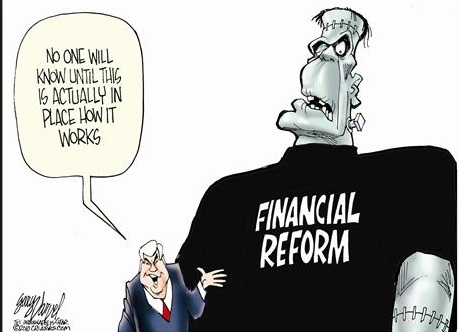

Complicating matters further is that risk-taking by banks – even at extreme levels – is not always unethical, rogue, or fraudulent. It often appears responsible and innovative. The problem with innovation is that no one can predict the precise impact it will have. In fact, the 2008-2009 financial crisis was more a consequence of error and misdirection than fraud and explicit misconduct by bankers.

Nonetheless, the kind of cultural and behavioral initiatives that Tarullo and Dudley proposed are worth pursuing. Indeed, aligning the financial interests of managers and senior bankers with regulators’ efforts to boost capital, reduce risk, and make bank failure a real possibility would go a long way toward making banks safer.