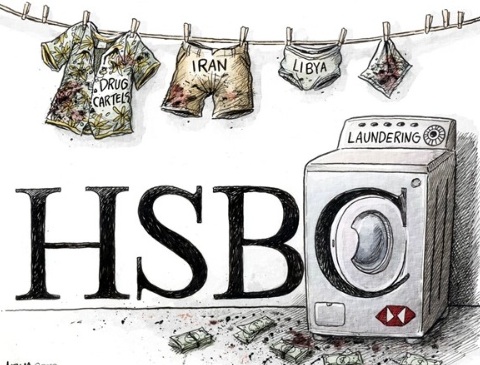

Here is a link to the files leaked from HSBC: Files

Category Archives: Big Banks

Does the Punishment Fit the Crime?

Jed. S. Rakoff reviews Too Big to Jail by Brandon L. Garrett: So-called “deferred prosecutions” were developed in the 1930s as a way of helping juvenile offenders. A juvenile who had been charged with a crime would agree with the prosecutor to have his prosecution deferred while he entered a program designed to rehabilitate such offenders.

The analogy of a Fortune 500 company to a juvenile delinquent is, perhaps, less than obvious. Nonetheless, beginning in the early 1990s and with increasing frequency thereafter, federal prosecutors began entering into “deferred prosecution” agreements with major corporations and large financial institutions. In the typical arrangement, the government agreed to defer prosecuting the company for various federal felonies if the company, in addition to paying a financial penalty, agreed to introduce various “prophylactic” measures designed to prevent future such crimes and to “rehabilitate” the company’s “culture.”

Speaking of corporate culture in an even broader way, it is worth remembering that any reasonable shareholder wants his or her company’s executives to be highly energetic, characterized by initiative, competitiveness, innovativeness, and even aggressiveness, all in a quest for profitability. It may be that these lauded qualities, essential to success in any competitive company, may in some cases encourage questionable behavior.

At bottom, corporate fraud amounts to little more than executives lying for business purposes, and prosecution depends on proving that the lies were intentional.

The preference for deferred prosecutions reflects some less laudable motives, such as the political advantages of a settlement that makes for a good press release, the avoidance of unpredictable courtroom battles with skilled, highly paid adversaries, and even the dubious benefit to the Department of Justice and the defendant of crafting a settlement that limits, or eliminates entirely, judicial oversight of implementation of the agreement.

When it comes to criminal violations involving corporations, “neither individuals nor corporations should be left off the hook.” One might argue that the two should not be equated and that the prosecution of high-level individuals for high-level crimes is a far more appropriate use of the criminal law than prosecution of the companies that served as their fields of operation. For the past decade or more, as a result of the shift from prosecuting high-level individuals to entering into “cosmetic” prosecution agreements with their companies, the punishment and deterrence of corporate crime has, for all the government’s rhetoric, effectively been reduced. Deferred Prosecution

Nigeria’s Bonds?

Nigeria having a tough time as oil prices plummet. Yet Nigeria will probably remain in JPMorgan Chase & Co.’s local-currency emerging-market bond indexes tracked by over $200 billion of funds, according to the central bank governor.

“The main issue was liquidity and we are convinced that liquidity has come up to the level they desire,” Governor Godwin Emefiele said by phone from Abuja. “It’s gone to a range of about $250 million to $300 million a day.”

JPMorgan placed Africa’s largest economy and oil producer on “index watch negative’’ for its GBI-EM indexes on Jan. 16, saying central bank measures in December had reduced foreign exchange and bond trading and made it difficult for investors to replicate the gauge. The New-York based lender said it would make a decision within five months.

Nigeria, which derives 90 percent of export earnings and 70 percent of government revenue from oil, has been battered by crude prices that have fallen by half since June.

The central bank increased interest rates to a record 13 percent in November in a bid to stem outflows and stabilize the naira, which has weakened 17 percent against the dollar in the past six months,

Whistleblowers of the World Unite?

In the original case against UBS there was one indispensible person: Bradley Birkenfeld. He had to do time, in jail and then at home with an electronic bracelet. But he also received $104 million from the Internal Revenue Service for making possible the collection of billions of dollars in unpaid taxes.

Why haven’t more people become whistleblowers? They are often the difference between prosecuting a case and not starting an action. They are certainly instrumental in winning cases. And people who blow the whistle can make huge sums of money.

It is a frightening action to take. You are going up against big companies and often ending your chance of being employed in your business of choice. The prospect of prison is also a deterrent.

Should governments consider amnesty for people who are willing to step up and expose the criminal cultures of the institutions in which they work? Transparency International writes: Whistleblowers are invaluable in exposing corruption, fraud and mismanagement. Early disclosure of wrongdoing or the risk of wrongdoing can protect human rights, help to save lives and preserve the rule of law.

Safeguards also protect and encourage people willing to take the risk of speaking out about corruption. We must push countries to introduce comprehensive whistleblower legislation to protect those that speak out and ensure that their claims are properly investigated. Companies, public bodies and non-profit organisations should introduce mechanisms for internal reporting. And workplace reprisals against whistleblowers should be seen as another form of corruption.

Public education is also essential to de-stigmatise whistleblowing, so that citizens understand how disclosing wrongdoing benefits the public good. When witnesses of corruption are confident about their ability to report it, corrupt individuals cannot hide behind the wall of silence.

UBS Still Aids and Abets US Tax Evaders

U.S. federal prosecutors have launched a new probe into whether Swiss bank UBS AG helped Americans evade taxes through investments banned in the United States. UBS, which paid $780 million in 2009 to settle a separate Justice Department tax-evasion probe, is now under investigation for allegedly helping wealthy clients hide assets through so-called bearer securities.

Bearer securities, which can be transferred without needing to register ownership, is largely restricted in the United States because they can be used for evading taxes and money laundering. Bearer bonds were often used by U.S. companies to issue debt in foreign countries.

Prosecutors in the U.S. attorney’s office in Brooklyn are looking into evidence gathered by the Federal Bureau of Investigation to find out whether the bank’s employees helped clients to evade taxes or engage in securities fraud.

Prosecutors are also investigating whether any executive was involved in criminally covering up any fraudulent conduct.

Authorities recently subpoenaed UBS regarding the investigation, and prosecutors and FBI agents visited London to interview potential witnesses, the report said.

UBS has hired a partner at Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz, to conduct an internal investigation.

Transparency at the US Fed?

Why is the Federal Reserve so reluctant to become transparent. Kevin CIrilli writesL The Federal Reserve is lashing out at Sen. Rand Paul’s plan to give Congress more oversight over the central bank, a proposal that could gain traction in the new Republican-led Congress.

The Kentucky Republican reintroduced his “Audit the Fed” legislation last month with 30 co-sponsors, including other potential 2016 GOP hopefuls, Sens. Ted Cruz (Texas) and Marco Rubio (Fla.).

The proposal — once championed by his father, former Rep. Ron Paul (R-Texas) —would subject the central bank to an audit by the Government Accountability Office (GAO).

Regional bank presidents from around the country are decrying the plan, which they argue could damage the economy. “Who in their right mind would ask the Congress of the United States — who can’t cobble together a fiscal policy — to assume control of monetary policy?” Richard Fisher, retiring president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas/

Fed Chairwoman Janet Yellen has already vowed to fight the legislation, and President Obama would likely veto it.

Still, Fed watchers note that Paul has become emboldened by the new Republican majority in Congress. And he possesses an ever louder national microphone, as he moves closer to a 2016 presidential run.

Together, those factors could elevate the issue in the coming months, a prospect that has spurred strong words from bank officials.

Retiring Philadelphia Fed President Charles Plosser told The Hill that financial auditing “already exists” for the Fed, and warned that Paul’s plan would empower Congress “to audit and question monetary policy decisions in real time.”

Paul pushed back against the criticism, saying Fed officials “will say and do anything to keep their business hidden from the American people.”

What the press has not made clear in reporting the Great Recession and quantitatie easing is the assets bought by the Fed and who they benetied. An audit by the rerpresentatives of the Ameican people might provide insights into exactly what happened and why the ordinary American citicen is still having a tough time.

Fed Chair Janet Yellen, who met with Senate Democrats last week on Capitol Hill, is scheduled to testify before Congress later this month. The appearance will be her first since Republicans seized control of the Senate, and she will likely face questions on the legislation.

Senate Banking Committee Chairman Richard Shelby (R-Ala.), whose panel has jurisdiction on the bill, has also said he is interested in holding hearings on the issue.

Private Investors for Bank Risk?

Sheila Bair writes: As Chairman of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation from 2006 to 2011, I have front line experience with the problems and havoc that can ensue when large, interconnected financial institutions take excessive risks. I am committed to protecting American taxpayers from any future bailout of these so-called “too big to fail” institutions. The best way to do that is to ensure these institutions have adequate private investment to absorb the losses when they fail. That allows markets to work as they should – with private investors accepting the risks and taking the losses, rather than the “heads I win, tails the public loses” practices we saw during the financial crisis where some large banks and other “systemic” institutions were allowed to reap the profits of their risk taking, but turn to taxpayers for help when those risks turned sour.

Big financial institutions profit by relying primarily on borrowed money – instead of shareholder equity – to fund their loans and investments. Because the market views them as implicitly backed by the government, it is cheaper for them to fund themselves with debt instead of equity. Through high levels of leverage, executives are able to increase their returns on equity – and their bonuses which are frequently tied to shareholder returns. Prior to the financial crisis, some of our biggest Wall Street banks were borrowing an incredible $30 to $40 for every dollar of hard cash they had from shareholders.

Big financial organizations have strong financial incentives to increase leverage. This is why it is essential for global and U.S. regulators to take a firm line on the amount of borrowing they are allowed to do. U.S. banking regulators have already moved to limit big bank borrowing to less than $20 for each dollar of shareholder capital, and just last month proposed further borrowing limits for the largest U.S. banks that exceed the minimums set by international regulators. But behind the scenes, they’re facing intense resistance from many Wall Street banks, who are lobbying them to roll back and weaken their rules.

In the long run, better capitalized banks are in the interests of shareholders, creditors, and the public at large. Though tougher capital rules may impact returns on equity in the short-term, in the long-term, thick cushions of capital protect investors against unforeseen risks and position the bank to continue lending during downturns. Numerous studies have shown that well capitalized banks do a better job of lending through cycles. This helps guarantee sustainable profits for shareholders, and reduces the risk of default for creditors. Most importantly, well-capitalized banks are in a stronger position to lend during times of economic distress when the economy needs them the most.

Growth in US?

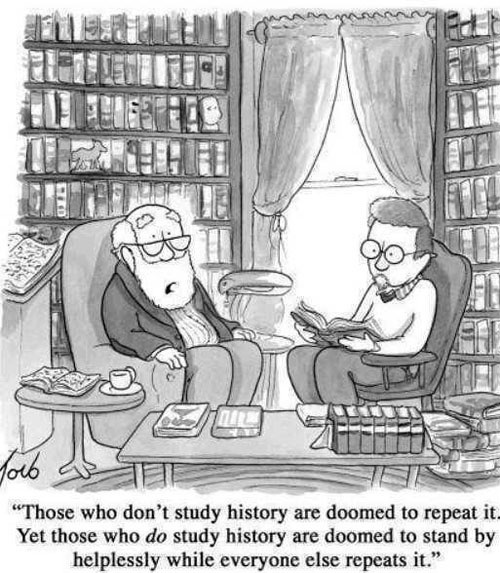

Federal Rserve Bank of San Francisco comments: Since 2007, Federal Open Market Committee participants have been persistently too optimistic about future U.S. economic growth. Real GDP growth forecasts have typically started high, but then are revised down over time as the incoming data continue to disappoint. Possible explanations for this pattern include missed warning signals about the buildup of imbalances before the crisis, overestimation of the efficacy of monetary policy of following a balance-sheet recession, and the natural tendency of forecasters to extrapolate from recent data. .

Economic forecasting can be a humbling endeavor. In a cross-country study of private-sector forecasts from 1989 to 1998, Loungani (2001) finds that “the record of failure to predict recessions is virtually unblemished.” He also finds that forecast revisions in one direction tend to be followed by further revisions in the same direction and that one-year-ahead growth forecasts are typically too optimistic. An updated study by Ahir and Loungani (2014) finds that the private-sector’s record of failure to predict recessions remained intact through 2008 and 2009. A study by Alessi, et al. (2014) finds that one-year-ahead growth forecasts from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York and the European Central Bank from 2008 to 2012 exhibited substantial overoptimism, averaging 1.6 to 2.4 percentage points above actual growth. The SEP growth forecasts fit the pattern of these various studies.Research shows that people tend to use simple forecast rules that extrapolate from recent data (Williams 2013).

Research has identified numerous instances of persistent bias in the track records of professional forecasters. These findings apply not only to forecasts of growth, but also of inflation and unemployment (Coibion and Gorodnichencko 2012). Overall, the evidence raises doubts about the theory of “rational expectations.” This theory, which is the dominant paradigm in macroeconomics, assumes that peoples’ forecasts exhibit no systematic bias towards optimism or pessimism. Allowing for departures from rational expectations in economic models would be a way to more accurately capture features of real-world behavior. Growth

Subprime Loan Bundling, Again?

Is securitizing sub-prime auto loans a disaster in the making? Across the country, there is a booming business in lending to the working poor — those Americans with impaired credit who need cars to get to work. But this market is as much about Wall Street’s perpetual demand for high returns as it is about used cars. An influx of investor money is making more loans possible, but all that money may also be enabling excessive risk-taking that could have repercussions throughout the financial system, analysts and regulators caution.

In a kind of alchemy that Wall Street has previously performed with mortgages, thousands of subprime autoloans are bundled together and sold as securities to investors, including insurance companies and hedge funds. By slicing and dicing the securities, any losses if borrowers default can be contained, in theory.

Led by companies like Santander Consumer; GM Financial, and Exeter Finance, such securitizations have grown 302 percent, to $20.2 billion since 2010. And even as rising delinquencies and other signs of stress in the market emerged last year, subprime securitizations increased 28 percent from 2013. The returns are substantial in a time of low interest rates. In the case of the Santander Consumer bond offering in September, which is backed by loans on more than 84,000 vehicles, some of the highest-rated notes yield more than twice as much as certain Treasury securities.

Now questions are being raised about whether this hot Wall Street market is contributing to a broad loosening of credit standards across the subprime auto industry. Companies are increasingly enabling people at the extreme financial margins to obtain loans to buy cars.

The intense demand for subprime auto securities may also be fueling a more troubling development: a rise in loans that contain falsified income or employment information.

Ms. Payne, a former administrative assistant in the New York Police City Department, has not made a single payment on a $30,770 Santander loan that was taken out to buy a 2011 BMW 328xi. Ms. Payne, who has no driver’s license, said she took out the loan so her daughter, who lives in New Jersey, could have a car. The loan has an interest rate of 11.89 percent.

Still, some credit analysts have questioned whether the market has grown too much, too fast. Some rating firms that faced criticism after the mortgage crisis for blessing shaky investments with top ratings are taking a critical approach to subprime auto deals.

Mr. Gillock, the financial adviser in Chicago, said that no bond made up of subprime auto loans should ever receive a triple-A rating — a designation that only three blue-chip companies receive on their debt offerings.

The financial crisis provided an opportunity for subprime auto loan securitizations.

With the once-enormous market in mortgage-backed securities largely frozen, investors looked for new opportunities. One bright spot was auto lending. Even in the depths of the recession, people needed cars and were willing to pay steep rates for a loan.

Sub-prime bundled auto loans may be the perfect example for anyone who thinks a big fine changes the culture of an investment firm. It has all the problems the subprime mortgage loans had in 2005.

.

Small Bank Regulation in the US

Frank Keating, president and CEO of the American Banker’s Association: I constantly hear from hometown bankers that their examiners—the government officials who visit their banks every year to make sure they make safe loans and follow the rules—are recommending actions suited for banks many times their size. They call it “trickle-down regulation.”

Here’s an example: I recently heard from the CEO of a community bank with $1 billion in assets. His examiner urged him to conduct a “stress test” that is only required for banks with $10 billion or more in assets. On the one hand, a stress test is expensive and time-consuming to conduct—not to mention completely unnecessary for a hometown bank with a traditional business model. But on the other hand, if my friend rejects his examiner’s suggestion, he might risk getting a poor regulatory rating that could hurt his bank. In this context, the suggestion really isn’t a suggestion at all.

You may have a hard time getting worked up about the costs of trickle-down regulation on banks. That’s understandable, because it’s hard to see the costs of excessive regulation. Rules from Washington, D.C., don’t directly come with a price tag. But their cumulative weight requires banks to hire more staffers and consultants to understand and follow them—just as you might hire an accountant to help with your taxes if the IRS required you to pay at a higher bracket. These staff members don’t make loans or sell financial products that serve bank customers, but they often must be paid well because of their specialized expertise.

The result, according to researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, is that when a small hometown bank hires additional staff to follow extra regulations, that bank’s already-slim profits shrink by anywhere from 11 to 37 percent. Those shrinking profits have real-world consequences for the bank’s town and the people who live there: less lending for small businesses and entrepreneurs, fewer mortgage loans and fewer investments in the financial technologies of the future.

But beyond the shadow costs that trickle-down regulation imposes on everyday Americans is the basic unfairness of arbitrarily making people follow rules they’re not required to follow. You’d be furious if the DMV failed your daughter for not knowing how to drive an 18-wheeler, and you’d be steaming if the IRS charged you a tax rate for a higher bracket. Bank examiners shouldn’t be allowed to make up their own rules, either.