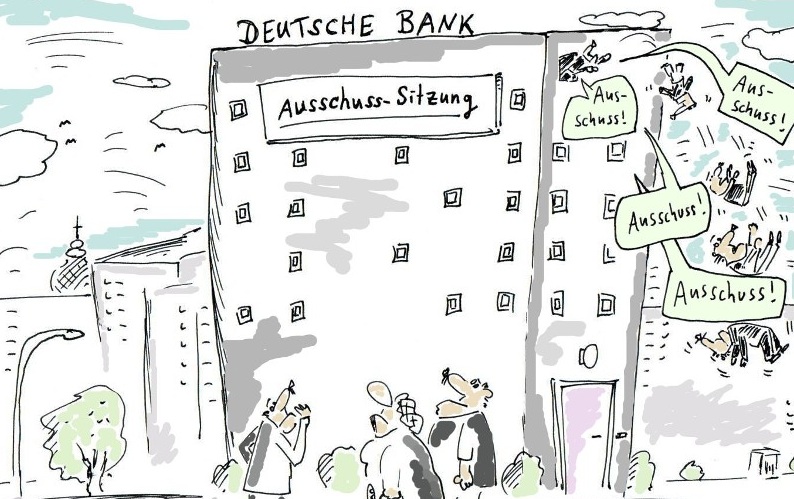

Deutsche Bank AG is weighing a sale of its consumer banking business in what would mark a reversal of its pledge to remain a universal bank, said two people with knowledge of the matter.

Selling the retail unit, or part of it, would free up capital and boost returns while also providing funds to absorb the cost of scaling back investment banking businesses that aren’t sufficiently profitable, said one person, who asked not to be identified because the deliberations are private.

Deutsche Bank has sought to keep a full-fledged investment bank and consumer-lending unit since Co-Chief Executive Officers Anshu Jain and Juergen Fitschen took over three years ago, even as rising capital requirements hurt profitability. The bank is completing a months-long strategic review to determine where it needs to trim operations to boost returns and capital levels.

A sale of the retail business will be positive for Deutsche Bank’s shares as the unit’s profitability has lagged behind peers, JPMorgan Chase & Co. analysts led by Kian Abouhossein wrote in a note to clients Monday.

The consumer unit, which includes small- and mid-sized business clients, had the lowest return on equity and the highest costs as a share of revenue of any of the company’s four units last year, its filings show.

The plan that would mark the biggest shift from the current model would see the Postbank unit and the other consumer operations bundled together and sold to the public in 2017, the person said. That option, which would also see the investment bank unit narrow its focus, is expected to provide the quickest increase in shareholder returns, the people said.

Deutsche Bank acquired Bonn-based Deutsche Postbank AG in 2010 to reduce its dependence on revenue from its trading and investment banking arm. The company also has a transaction banking as well as an asset and wealth management unit.

Another scenario would see the company’s Postbank unit merge with other consumer businesses and cuts made across Deutsche Bank, including the investment bank, said one person. The results would take as long as five years to take full effect, said the person.

A third option would be a sale of Postbank, which would free up capital by allowing the bank to shrink risk-weighted assets by about 45 billion euros, the person said.

Cuts at the investment bank would focus on the company’s business with hedge funds as well as parts of its derivatives and interest-rate trading desks that don’t serve corporate customers.

Deutsche Bank brand branches as clients increasingly use online banking, Die Welt reported on Monday, citing unidentified people familiar with the matter. Cuts to Postbank’s 1,100 branches are also possible, the newspaper said.