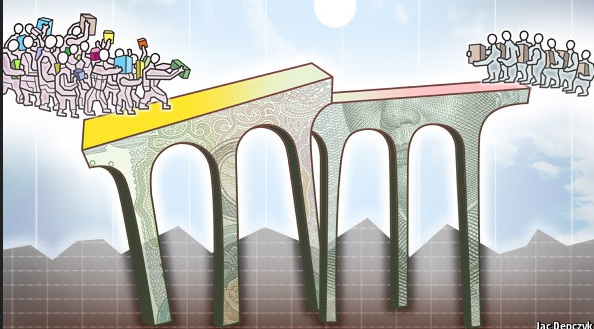

Paolo Noguiera Batista and Hector R. Torres write: More than four years have passed since an overwhelming majority of the membership of the International Monetary Fund agreed to a package of reforms that would double the organization’s resources and reorganize its governing structure in favor of developing countries. But adopting the reforms requires approval by the IMF’s member countries; and, though the United States was among those that voted in favor of the measure, President Barack Obama has been unable to secure Congressional approval.

The delay by the US represents a huge setback for the IMF. It stands in the way of a restructuring of its decision-making process that would better reflect developing countries’ growing importance and dynamism.

In our view, the best way forward would be to decouple the part of the reforms that requires ratification by the US Congress from the rest of the package. Only one major element – the decision to move toward an all-elected Executive Board – requires an amendment to the IMF’s Articles of Agreement and thus congressional approval.

The other major element of the reform package is an increase and rebalancing of the quotas that determine each country’s voting power and financial obligation. This change would double the IMF’s resources and provide greater voting power to developing countries. Congress would still need to ratify the measure before the US’s own quota increased, but its approval would not be required for this part of the reform package to take effect for other countries.

The connection between the two parts of the reforms has always been unnecessary; the measures are independent, require different approval processes, and can be delivered separately. Removing the link between them would require the support of the US administration, but not ratification by Congress.

This separation could be implemented smoothly. A simple majority of the IMF’s Executive Board would recommend it to the Board of Governors, where a resolution separating the reforms into two parts would require 85% of the votes.

The changes to the quotas could then quickly become effective.

The key obstacle to this proposal is the requirement of congressional approval to increase America’s quota share. This opens the possibility that the US’s voting power could temporarily fall below the 15% threshold needed to veto decisions that require the support of 85% of IMF members’ votes.

In order to secure US support, the Board of Governors could commit not to consider any draft decision requiring 85% backing without America’s consent. This guarantee could be included in the resolution dividing the reform package into two parts. It would remain valid until the US was in a position to increase its quota and recover its voting share.

The agreement could also act as an incentive for ratifying the reforms. The power to reinstate the US’s formal veto power would lie entirely in the hands of Congress – making it unlikely that another four years would pass before the matter is finally resolved.