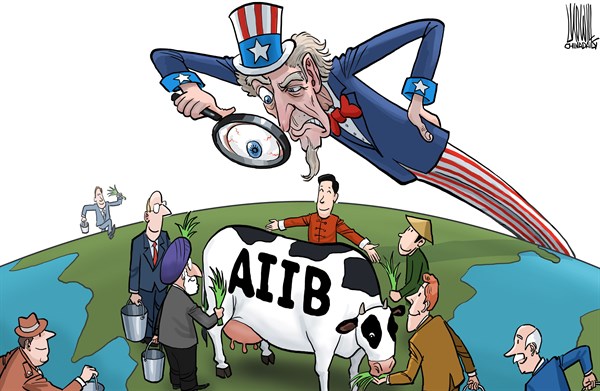

Mark Fleming-Williams writes: Former U.S. Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers wrote on April 5 that this month may be remembered as the moment the United States lost its role as the underwriter of the global economic system. His comments refer to the circumstances surrounding China’s launch of a new venture, the Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank, (AIIB). Wary of China’s growing ambitions and influence, the United States had advised its allies not to join the institution, but many signed up anyway. The debacle was undoubtedly embarrassing for Washington, but even so, Summers’ prophecy is a bit premature at this stage. US Economic Dominance

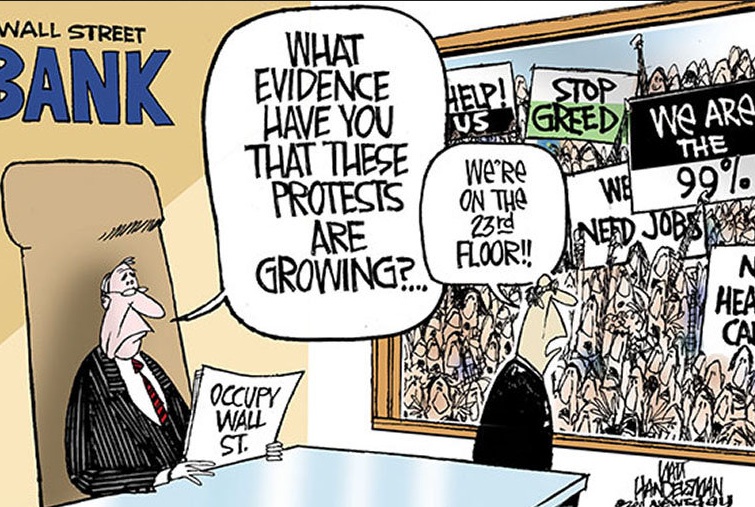

Category Archives: Big Banks

Wall Street’s Stringer?

Matt Levine points out how politics works US style. Particularly in New York, the traditional home of US finance:

Remember how New York City Comptroller Scott Stringer was shocked to find out that New York’s pension funds pay investment management fees to “Wall Street”? Which includes paying a few basis points to traditional stock and bond managers, and one or two hundred basis points to “alternatives” (private equity, real estate, etc.) managers?

Stringer was pushing Albany lawmakers to pass a bill that would have allowed an additional 10 percent of the city’s $160 billion pension system — or $16 billion — to be invested in alternatives. Assuming the industry standard 2 percent management fee on such investments, that shift could have generated more than $300 million in new Wall Street fees every year.

Stringer championed the bill following a 2013 election campaign that saw him benefit from an influx of campaign contributions from financial executives after former Wall Street prosecutor (and former governor) Eliot Spitzer jumped into the race for comptroller. During the campaign, Stringer declared that he wanted the city to consider moving more pension money out of low-risk bonds and into Wall Street firms. Upon taking office in 2014, he argued that the existing law prohibiting more than a quarter of the city’s pension fund from being invested in alternatives was too restrictive.

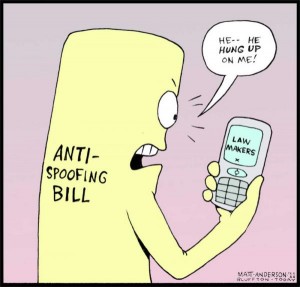

Can Policy Change on High Speed Trading?

Everett Rosenfeld writes: A UK trader is charged for manipulation contributing to 2010 flash crash.

A high-frequency futures trader has been charged with illegally manipulating the stock market, contributing to the May 2010 “flash crash,” according to documents unsealed Tuesday.

The US Justice Department charged the United Kingdom’s Navinder Singh Sarao with wire fraud, 10 counts of commodities fraud, 10 counts of commodities manipulation and one count of spoofing (which is when a trader places a bid or offer with the intent to cancel before execution).

Sarao was arrested Tuesday in the U.K., and the U.S. is requesting his extradition, the DOJ said. The charges were filed in a federal complaint in February, but were unsealed Tuesday following the arrest.

The Commodity Futures Trading Commission also filed parallel civil charges against Sarao on Tuesday, calling him a “very significant player in the market.”

The CFTC alleged that Sarao was believed to have profited by about $40 million for his scheme. U.S. authorities have frozen nearly $7 million worth of his assets and accounts, Aitan Goelman, CFTC director of enforcement.

QE and the Fate of the Yen

Walter Kurtz writes: At the end of last October the Bank of Japan annnounced a large stimulus increase which was followed by a sharp decline in the yen. In 2015, however, even though the extraordinary monthly securities purchases are continuing, the declines have stopped as USD/JPY remains range-bound.

In the long run however, further yen weakness seems inevitable. The reason has to do with the sheer relative size of Japan’s quantitative easing. Based on the latest projections, the BoJ’s balance sheet will be above 90% of Japan’s GDP within a year or so. This dwarfs other major central banks’ monetary expansion efforts, including that of the ECB. Furthermore, given the scope and size of this program, it is unclear if the Bank of Japan can ever effectively exit it without a massive disruption to the nation’s economy. While we could see the yen strengthen briefly in the near-term, the currency will remain under pressure for some time to come.

Elizabeth Warren Asks the Right Questions

Elizabeth Warren: Real accountability also requires big changes within our regulatory agencies. In 2013, the Fed and the OCC entered into a $9.3 billion settlement with more than a dozen mortgage servicers who had improperly foreclosed on thousands of homes across the country.[13] Congressman Cummings and I started asking some questions about this, and we stumbled onto a pretty amazing fact. The Fed’s Board of Governors – the ones who were nominated by the president and confirmed by the Senate – didn’t even vote on whether to accept the settlement. A recordbreaking $9.3 billion on the table, and the settlement decision was left to the Fed’s staff. Elizabeth Warren on Financial Reform

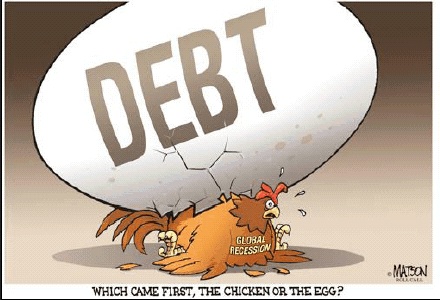

Dealing with Debt Globally

Adair Turner and Susan Lund write: Greece’s divisive negotiations with the EU have placed debt back at the center of debates about economic growth and stability. But Greece is not the only country struggling to repay its existing debt, much less dampen borrowing. Its fraught negotiations with its creditors should spur other countries to take action to address their own debt overhangs.

Since the global financial crisis erupted in 2008, the world’s debt has risen by $57 trillion, exceeding GDP growth. Government debt has increased by $25 trillion, with the advanced economies accounting for $19 trillion – a direct result of severe recession, fiscal-stimulus programs, and bank bailouts.

Much of this debt accumulation was driven by efforts to support economic growth in the face of deflationary headwinds after the 2008 crisis. That was especially so in China, which, together with other developing economies, accounts for nearly half of the debt incurred since 2008.

To be sure, debt itself is not bad. But excessive reliance on debt creates the risk of financial crises, which undermine growth. Given this, the world needs to find both less credit-intensive routes to growth and ways to eliminate existing debt burdens.

To help limit future debt accumulation, countries have three options. First, they can employ countercyclical macroprudential measures to dampen credit cycles and prevent excessive borrowing. For example, stricter loan-to-value-ratio limits and higher capital requirements for banks could slow credit growth when housing or commercial real-estate markets are overheating. Yet precisely the opposite approach is now being taken in the United States, where some first-time homebuyers have now been given access to 97% loan-to-value mortgages.

A second strategy for curbing the buildup of debt could be to introduce mortgage contracts that enable more risk sharing between borrowers and lenders, essentially acting as debt/equity hybrids. As the Great Recession grimly illustrated, when a period of soaring real-estate valuations and rising household debt is followed by a period of falling prices, and households attempt to deleverage, the results can be catastrophic. The talent for financial innovation that produced harmful new home-mortgage options before the crash should now be harnessed to develop more flexible mortgages that help borrowers avoid default.

One example is “shared responsibility” mortgages, in which payments are reduced under certain circumstances, such as when home prices dip below the borrower’s purchase price. In exchange for this flexibility, the lender receives a share of any capital gain that is realized when the home is sold. Similarly, the continuous-workout mortgage adjusts payments and terms in specific cases, such as job loss.

A third option for limiting debt accumulation is to reconsider tax rules that favor debt. In many countries, interest accrued on a mortgage remains tax deductible. Though phasing out this policy is politically contentious, some countries – such as the United Kingdom in the 1980s – have managed to do so. Similarly, it would be difficult – but not impossible – to reduce the incentives, created by almost all countries’ tax regimes, for corporate leverage.

Governments must also work to reduce existing debt – and the deficient global demand to which it contributes. It is simply not feasible for the most highly leveraged governments to grow their way out of debt. Nor can austerity alone suffice, as it would require countries to make such large fiscal adjustments – 5% of GDP, in Spain’s case – that citizens would likely resist them, as the Greeks have done.

A more effective approach would employ a broader range of tools, including debt restructuring. In some countries, sales of public assets and the levying of one-off wealth taxes would also be helpful.

The US Federal Reserve, the Bank of England, and the Bank of Japan now own 16%, 24%, and 22%, respectively, of all bonds outstanding.

Given that central banks are owned by the government, and that interest paid on outstanding bonds is remitted back to the national treasury, these government bonds are fundamentally different from those owned by other creditors. Focusing on “net” government debt (which excludes intra-government debt holdings, such as the bonds owned by central banks) is a more effective approach to assessing and ensuring the sustainability of public debt.

The global economic crisis laid bare the challenge of debt reduction – and the risks that excessive indebtedness raises. Yet the crisis also intensified government and household dependence on leverage, causing debt levels to continue to rise – a trend that, left unchecked, will lead to more crises in the future.

Bail in or Bail Out: That is the Question?

Ken Workman discusses reaction to the true but politically incorrect remark of Jeroen Djisselbloem. The fact—and the fear—is that the Eurogroup is changing expectations again: When they bailed out Greece, creditors got restructured, but Europe promised it was a one-time only thing. The ECB bailout of Spain was different: You guys recapitalize the banks, creditors stay whole, and the ECB provides the financing. When Cyprus, and its role as Russia’s offshore bank came along, European leaders responded by reverting to the Greek model: Creditors got “bailed-in” and had to take losses.

Customers at banks in Spain and Italy and France now realize that if their countries and banks end up in need of further financial assistance to stay in the euro zone, the private sector might have to take losses. This is already causing bank stock prices to drop, prompting a quick walk-back (pdf) that left everyone confused.

Customers at banks in Spain and Italy and France now realize that if their countries and banks end up in need of further financial assistance to stay in the euro zone, the private sector might have to take losses.

The problem is that while Cyprus is special, it’s not that special. Germans don’t want to bailout Russian depositors, but they also don’t want to bail out anyone. The Spain model isn’t working and the expectation that it will means disappointment. A euro zone mired in recession is not going to be able to out-grow its debt problem with a weak financial system. The EU needs a banking union, something the Eurogroup has already begun work on. Recognizing reality may make markets nervous, but to solve the crisis, public and private creditors will have to pay up.

That doesn’t make Cyprus ideal by any stretch of the imagination. Cypriots would probably be better off leaving the euro altogether. And the haphazard assembly of its bailout has left only two real principles intact: the euro will not be allowed to fail, and creditors will likely need to help with that. Balancing crisis management (stopping bank runs) with reform (recapitalizing banks) is never easy, but after four years it might be worth thinking more clearly about the tensions between the two.

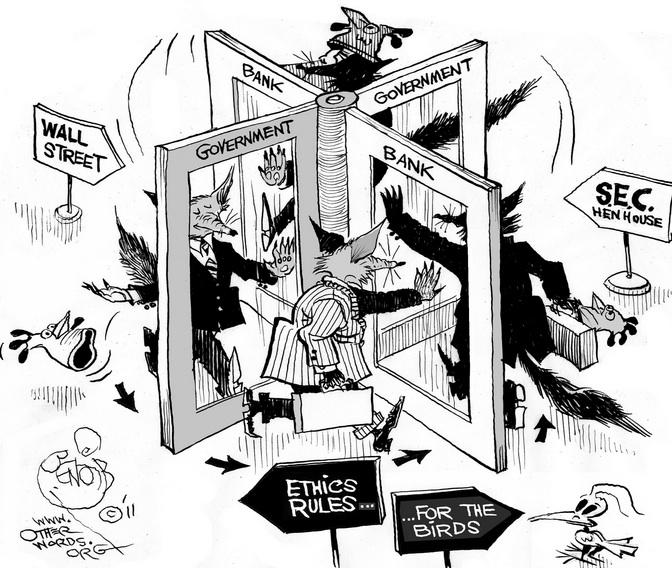

Is the Revolving Door from Government to Finance Dangerous?

Ben Bernanke, the former chairman of the US Federal Reserve, has joined Citadel as an adviser on monetary policy, arriving as the Chicago hedge fund recovers from a $1bn loss trading government bonds.

The ex-central banker, who stepped down from the Fed in January 2014, said he would be adding his “perspective on a range of issues affecting our global economy” in his new role.

The move may fan criticism of the revolving door between the Fed and other wings of government and powerful financial firms.

Alan Greenspan, Mr Bernanke’s predecessor as Fed chairman, took up positions including acting as a consultant for Deusche Bank and hedge fund Paulson & Company after leaving the central bank.

Last month, Jeremy Stein, a former Fed governor, said he would start advising BlueMountain Capital Management, another fund.

Mr Bernanke said he was sensitive to anxieties about the “revolving door” and had chosen Citadel, rather than a position at a bank, in part because it is not regulated by the Fed. He said he would not be doing “lobbying of any sort”.

Ken Griffin, the founder and chief executive of Citadel, which has $26bn in assets under management, said Mr Bernanke has “extraordinary knowledge of the global economy and his insights on monetary policy and the capital markets will be extremely valuable to our team and to our investors.”

The appointment was announced on Thursday, hours before it emerged that Citadel’s head of fixed income, Derek Kaufman, had resigned after suffering $1bn of losses in his portfolio of developed market sovereign bonds.

People familiar with the situation said a series of macro bets went awry in 2014, dragging down the overall performance of Mr Kaufman’s 20-person team.

After a weak start to trading in 2015, he resigned two weeks ago. A former JPMorgan proprietary trader, Mr Kaufman was recruited by Citadel in 2008.

Mr Kaufman’s team was responsible for a $4bn global fixed income fund, which managed only a 0.75 per cent gain last year, and for portions of Citadel’s flagship Kensington and Wellington funds. The fixed income team will now report directly to Mr Griffin.

“Citadel is a dynamic firm with tremendously talented people and a rigorous approach to research and investing. I look forward to adding my perspective on a range of issues affecting our global economy,” said Mr Bernanke in a statement released by Citadel.

Since leaving the Fed, Mr. Bernanke’s views have been solicited by hedge fund managers and other market participants at exclusive dinners and speaking engagements. He will be a speaker at next month’s SALT conference for hedge fund managers in Las Vegas.

Mr Bernanke served as chairman of the Fed from February 2006 to January 2014, putting him at the helm of the central bank in the midst of the financial crash. Before his appointment as chairman, he chaired the president’s council of economic advisers from June 2005 to January 2006.

What’s Draghi Up To?

Mohamed El-Erian writes: European Central Bank President Mario Draghi painted a dovish and hopeful picture and was also realistic about what euro zone governments need to do to enable the ECB’s full success.

Draghi left no doubt the ECB is committed to the implementation of its “non-standard” monetary policy. He reiterated that the central bank “intends” to intervene in markets until the end of September 2016, regardless of concerns about negative nominal yields and a possible shortage in securities to purchase. And it would continue beyond that date if the bank doesn’t obtain the macroeconomic outcome the quantitative easing program is designed to achieve.

To make this point even more forcefully, Draghi dismissed concerns about QE’s inadvertent collateral damage. These include accentuating the future risks of financial instability and enabling governments to be less responsible.

Turning to the impact of QE, Draghi was optimistic about the initial results. He pointed to the improvement in credit flows and other monetary indicators; and he took comfort from the stronger momentum of the euro zone economy, notwithstanding substantial variations among countries. In doing so, he played down concerns that ECB policy was encouraging financial bubbles, though he only seemed focused on bank leverage.

What Draghi didn’t make clear is that the euro zone’s experience of QE closely resembles those of other countries that had previously undertaken such efforts, particularly Japan and the U.S.

As was the case elsewhere, the first stages of the ECB’s program were immediately met with a helpful response in financial markets, including higher equity prices, lower bond yields and a depreciated currency. This response boosted sentiment more broadly and partially spilled over into economic activity. That was the easy part, which I previously described as the first third of the QE journey.

The remaining two-thirds will be much harder. Success requires sustaining economic progress while, simultaneously, containing the “costs and risks” associated with artificially boosted asset prices and possible resource misallocations. To navigate that artfully, the ECB will need a lot of help from other institutions.

As noted by Draghi, the ultimate success of the ECB’s unconventional policy approach will require governments to implement deeper structural reforms — including in labor and product markets — as well as encourage business investment and expansion. It will need much more pronounced balance-sheet healing, including overcoming increasingly entrenched debt overhangs. And, in my opinion, it also needs aggregate demand within Europe to be higher and more evenly spread across countries.

Europe is still quite a distance from achieving any of this. The celebration of the encouraging start of the euro zone’s QE should be tempered by the lessons of similar policies elsewhere.

Wolfgang Schäuble on Sensible Finance Policy

he immediate sting of the global financial crisis has faded in much of the world. Unfortunately, however, the world economy is not yet out of the woods. It still faces very concrete challenges. We are as badly as ever in need of a common understanding of what needs to be done

Complaints that the European response to the crisis has been ineffective at best, or even counterproductive — are simply not accurate. There is strong evidence that Europe is indeed on the right track in addressing the impact, and, most importantly, the causes of the crisis.

First, it has often been said that German insistence on fiscal austerity meant that Germany, the largest economy in the European Union, has “punched below its weight” — and thereby pushed the eurozone more deeply into crisis — by not stimulating more demand. This misses the point. The crisis in Europe was first and foremost a crisis of confidence, rooted in structural shortcomings. Investors started to realize that the member countries of the eurozone were not as economically competitive or financially reliable as the uniform bond yields of the pre-crisis years had suggested. These investors began to treat the bonds of certain countries with much more caution, causing interest rates for those bonds to rise.

Germany has consistently advocated an approach of structural reforms and reducing public debt without throttling growth. This is not blind “austerity.” It is about setting a reliable framework for private-sector activity, preparing aging societies for the future and improving the quality of public budgets.

In Germany, this approach has shown tangible success: The economic recovery since 2009 has been broad-based, with domestic demand as the main driver of growth. Investment — both public and private — is increasing. We are speeding up debt reduction, in line with the I.M.F.’s recent call for “symmetric stabilization” (reducing deficits in good times, to offset deficits in bad times).

Many European countries are reaping the rewards of reform and consolidation efforts. Countries like Ireland and Spain, which put far-reaching reforms into effect when they hit financial trouble a few years ago, now boast some of the highest growth rates in Europe.

Some make the absurd claim that Germany — being a creditor nation— is actually profiting from the crisis. It is true that the German government now enjoys historically low borrowing costs. But so do almost all other eurozone members. Unconventional monetary policies pursued by the independent European Central Bank seem to have fulfilled their part there. Low interest rates help all borrowers — but they come at ever-increasing costs to savers and pension funds.

Some say the answer to the crisis in Europe has been ever-greater liquidity and ever-lower interest rates. Now that we have both, we are finding that these policy tools are no panacea, but create problems of their own. More and more experts on both sides of the Atlantic warn of dangerous bubbles in asset prices and risks to financial stability from ever-increasing leverage (financing by borrowing). And it is clear that the debt burden in many countries cannot be solved by incentives to take on even more debt.

On the fiscal side, we need to prepare government budgets for an eventual normalization of monetary policy and capital markets.

The European Central Bank has warned many times that monetary policy cannot substitute for fiscal and structural reforms in member countries. Christine Lagarde, the managing director of the I.M.F., has also called for further structural reforms.

The priorities for Germany, as the current president of the Group of 7 nations, are modernization and regulatory improvements. Stimulus — both in fiscal and monetary policy — is not part of the plan. When my fellow finance ministers and the central bank governors of the G-7 countries gather in Dresden at the end of next month we will have an opportunity to discuss these questions in depth, joined — for the first time in the G-7’s history — by some of the world’s leading economists.