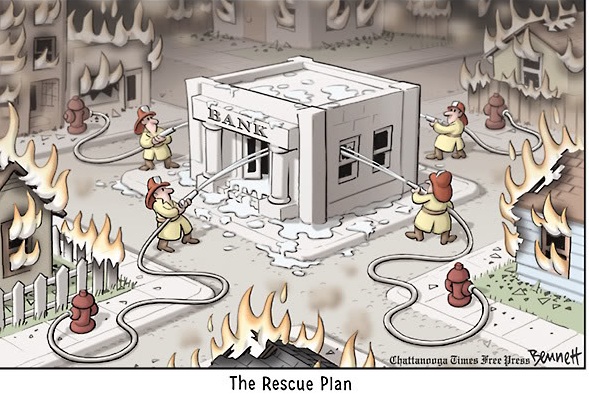

New York Federal Reserve comments The Federal Reserve is responsible for the prudential supervision of bank holding companies (BHCs) on a consolidated basis, as well as of certain other financial institutions operating in the United States. Prudential supervision involves monitoring and oversight of these firms to assess whether they are in compliance with law and regulation and whether they are engaged in unsafe or unsound practices, as well as ensuring that firms are taking corrective actions to address such practices

Prudential supervision is inter-linked with, but distinct from, regulation of these firms, which involves the development and promulgation of the rules under which BHCs and other regulated financial intermediaries operate. The distinction between supervision and regulation is sometimes blurred in the discussion by academics, researchers and analysts who write about the banking industry, and the terms “supervision” and “regulation” are often used somewhat interchangeably. Moreover, while prudential supervision is a central responsibility of the Federal Reserve and consequently accounts for substantial resources, the responsibilities, powers and day-to-day activities of Federal Reserve supervision staff are often not very transparent to those outside of the supervision areas of the Federeal Reserve System.

The primary focus of this discussion is on the supervision of large, complex bank holding companies and of the largest foreign banking organizations (FBOs) and non-bank financial companies designated by the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC) for supervision by the Federal Reserve. The paper focuses on oversight of these firms because they are the most systemically important banking and financial companies and thus prudential supervision of them is especially consequential. Given their size and complexity, the approach to supervision of these companies also differs from that taken for smaller and less complex firms. It is important to note that supervision of these large, complex firms is conducted through a comprehensive System-wide program governing supervisory policies, activities and outcomes.The discussion in this paper focuses solely on supervisory staff located at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, whose activities are carried out as part of this broader program. Supervising Too Big to Fail