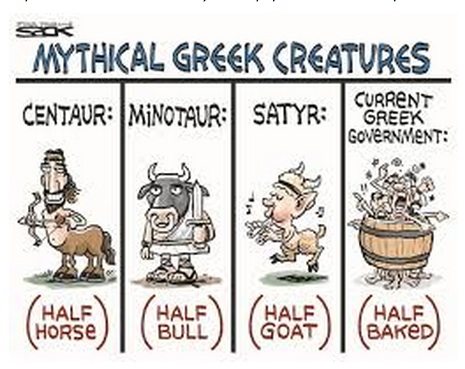

Edmund S. Phelps writes: Too many politicians and economists blame austerity – urged by Greece’s creditors – for the collapse of the Greek economy. But the data show neither marked austerity by historical standards nor government cutbacks severe enough to explain the huge job losses. What the data do show are economic ills rooted in the values and beliefs of Greek society.

Greece’s public sector is rife with clientelism (to gain votes) and cronyism (to gain favors) – far more so than in other parts of Europe.

There are serious ills in the private sector, too – notably, the pervasive influence of vested interests and the country’s business and political elites. Profits as a share of business income in Greece are a whopping 46%. Insiders receive subsidies and contracts, and outsiders find it hard to break in. Astoundingly, young Greek entrepreneurs reportedly fear to incorporate their firms in Greece, lest others use false documents to take away their companies.

This stunted system springs from Greece’s corporatist values, which emphasize social protection, solidarity instead of competition, and discomfort with uncontrolled change.

Greece saw productivity gains after World War II – but mostly from increases in education and capital per worker, which can go only so far. Two important sources of broad prosperity are blocked by Greece’s system. One is an abundance of entrepreneurs engaged in detecting and exploiting new economic opportunities. The other source of broad prosperity is an abundance of business people engaged in conceiving and creating new products and processes.

Some economists believe that these structural considerations have nothing to do with Greece’s current crisis. In fact, a structuralist perspective illuminates what went wrong – and why.

For several years, Greece drew on the EU’s aptly named “structural funds” and on loans from German and French banks to finance a wide array of highly labor-intensive projects. Employment and incomes soared, and savings piled up. When that capital inflow stopped, asset prices in Greece fell, and so did demand for labor in the capital-goods sector.

With competition weak, entrepreneurs did not rush to hire the unemployed. When recovery began, political unrest last fall nipped confidence in the bud.

The truth is that Greece needs more than just debt restructuring or even debt relief. If young Greeks are to have a future in their own country, they and their elders need to develop the attitudes and institutions that constitute an inclusive modern economy – which means shedding their corporatist values.

Europe, for its part, must think beyond the necessary reforms of Greece’s pension system, tax regime, and collective-bargaining arrangements. While Greece has reached the heights of corporatism, Italy and France are not far behind – and not far behind them is Germany. All of Europe, not just Greece, must rethink its economic philosophy.