After all the shouting, are we any closer to knowing whether free trade agreements are good or bad for the country – and for your wallet?

The attempts to provide answers to those questions have been thrust into the spotlight by President Barack Obama’s futile last-minute efforts to salvage his power to freely negotiate what would be the world’s largest free trade pact, the Trans-Pacific Partnership.

In the eyes of those within his own party, including the House minority leader, Nancy Pelosi, free trade agreements have been disastrous for ordinary Americans, hurting their wages, eroding the health of entire manufacturing sectors and putting the United States at a disadvantage against countries that engage in underhand trade practices. Their success last week managed to strip Obama of fast-track negotiating authority, pushing him into an unusual partnership with congressional Republicans in an effort to find a way to rescue the package of legislation by restructuring it. If you thought the political battle over Obamacare was high drama, just wait until Obamatrade really gets going.

Negotiating a free trade agreement is always going to involve a leap of faith – a leap of faith in the future. There are simply far too many variables involved, and too many “unknown unknowns”.

Consider the US-South Korea free trade agreement, completed in 2010 and in effect from 2012. Far from helping US exports to South Korea to climb, they have fallen as imports from South Korea have risen, causing the trade deficit to widen.

The problem with those who try to draw conclusions about free trade agreements in general from this example, however, is twofold. Firstly, it covers the experience of only about two years: an absurdly short time frame. Secondly, economic growth rates in South Korea peaked in 2010, the year the free trade pact was negotiated and all those rosy forecasts about US exports were drawn up. Right now, however, the economic picture looks bleak, and it’s probably fair to say that few expected that would happen.

The picture gets even more muddled if you try to look at the grandaddy of all free trade agreements, the North American Free Trade Agreement, or Nafta. Signed by Canada, the US and Mexico in 1992, Nafta was a model for many of the large trade agreements that followed, including TPP; it also was one of the first free trade pacts between economies with varying standards of living, labor standards and other business and environmental rules.

Critics argue that by 2010, a total of 682,900 jobs had been lost to Mexico, on a net basis. Of these, 415,000 were manufacturing jobs, many of which paid healthy living wages. Meanwhile, a small trade surplus with Mexico had become a deficit by 2000.

Had those jobs not gone to Mexico, would they have stayed in the United States? Not necessarily, suggested Mauro Guillén, a management professor at the Wharton School of Business; they might well have ended up in China. Meanwhile, some of the products made in Mexico are still being designed in the United States, he has noted.

In 1995, the year after Nafta took effect, Mexico had its own financial crisis, causing the value of the peso to nosedive and triggering a recession. As is the case with South Korea today, events that had nothing to do with the free trade agreement itself ended up causing a big drop in Mexican imports from the United States. The timing, however, made it appear as if the trade deficit was tied to free trade – but correlation isn’t causation. More recently, US demand for crude oil produced by Mexico, and the high prices for crude, sent that trade deficit higher again. Once again, that imbalance had nothing to do with free trade and everything to do with a supply/demand imbalance for crude oil within the United States.

American incomes have continued to stagnate in the period since Nafta kicked off the negotiation of free trade agreements. Again, however, correlation isn’t causation. The biggest culprits may include technology that has made it easier for workers in low-wage countries like China to do jobs that were once done here in the United States – or the policies of companies with respect to how they treat their work force. Apple already can choose to make its products in China, Vietnam or the United States. Their choice is clear. David Autor, an economist at MIT, argues that it is the spike in global trade, not free trade agreements, that has led to this result; he calculates that imports from China (not party to any free trade agreement with the United States) are responsible for 21% of the plunge in American manufacturing.

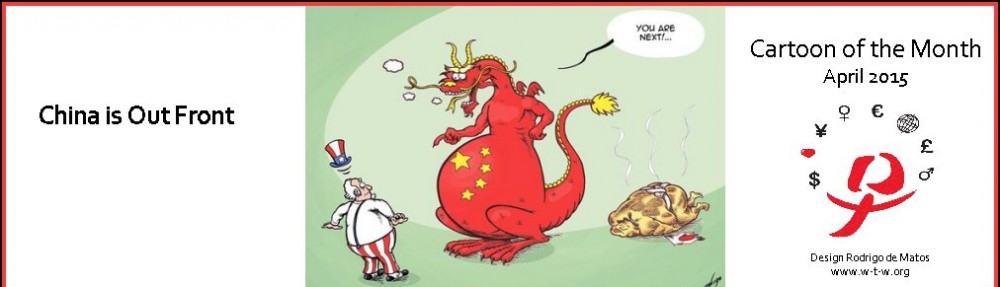

None of this means that the TPP is certain to be a great idea – or a bad one. Folks like the president and David Autor may argue all they like in favor of the pact, suggesting that it will give us an edge against China and, by protecting our intellectual property, help us expand our exports of computer services. Critics can charge that it will be a disaster, costing millions of jobs, accelerating climate change and doing untold damage to everything from our access to healthcare to worker’s rights.

It’s a roll of the dice.