Author Archives: Susan_Hall

Whose Problems Should the US Federal Reserve Address?

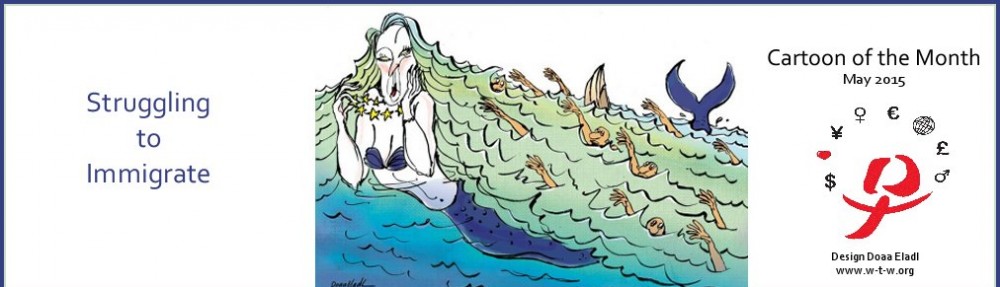

The Crisis in Financial Markets Began Before COVID-19.

The Federal Reserve has been committing hundreds of billions to short-term lending markets for months. It’s time to make that power work for more than just Wall Street, Matt Stoller and Graham Steele suggest.

Well before the pandemic, the Fed injected hundreds of billions of dollars into repo markets for reasons that are unclear.

Last week, the Federal Reserve staged a large-scale intervention in short-term money markets, announcing that it would make $1.5 trillion in loans available in the coming days. It followed with a big rate cut. And this week, the Federal Reserve is going to start lending to any big corporation that needs it, an emergency measure it last took during the 2008 financial crisis. It will be lending essentially unlimited sums to hedge funds, banks, and brokerages.

These subsidies to the financial sector might make sense today, because the COVID-19 pandemic was unexpected and every sector is having problems. The central bank must act and act boldly at such a moment.

But it’s important to divide up responses to the pandemic into shocks to the system that are a necessary result of an unexpected catastrophe, and preexisting problems that we never addressed that are made worse by the outbreak. Seen in that light, what the Fed is doing looks much riskier than it first appears. While the scale of the Fed’s announcement dwarfs its preceding interventions, this was the third of its kind in just the last six months.

Before fears of a recession driven by the impact of COVID-19, there were funding squeezes in the fall and winter of 2019, caused by as-yet unidentified factors. What we do know is that we never fixed the plumbing of the financial system after the 2008 financial crisis, because it’s more profitable for certain financial actors to rely on the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet than to force them to act responsibly. Defenders of the status quo ignore the fundamental questions raised by the fact that shocks, both large and small, have required the Fed to repeatedly prop up short-term credit markets.

Without getting too technical, here’s what’s going on. You and I deposit and borrow money in a simple, regulated system. We get loans through a bank or credit card company, and deposit money in banks guaranteed by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. If our bank goes under, our bank account is guaranteed up to $250,000 by the government.

But hedge funds, brokerages, and big corporations operate in a different banking system. They essentially deposit and borrow money using instruments called “repurchase agreements,” commercial paper, and money market funds, all of which are key parts of what is called the “shadow banking” sector. These instruments are mostly unregulated, which means they can cause bank runs. The government agency charged with investigating what caused the 2008 crisis found that the lack of regulation in this shadow banking sector was a key cause of the crisis.

In 2008, after runs in the shadow banking markets, the Federal Reserve established a variety of rescue programs, lending billions of dollars to keep credit flowing between financial institutions—one of which the Fed has now reopened. But well before the pandemic, throughout last fall and winter, the Fed injected hundreds of billions of dollars into repo markets to ensure proper liquidity and keep interest rates from skyrocketing. Nobody really knows why that was necessary, and faced with today’s crisis, it’s more of an afterthought. But it speaks to the continued instability in these markets.

Short-term funding markets are smaller and more resilient now than they were during the financial crisis, but they still account for trillions of dollars in daily lending. Part of the reason for that is the Fed’s generosity, providing liquidity to the repo market. Still, former banking regulator Daniel Tarullo the panics produced by volatile short-term funding are one of the “greatest risks to financial stability” remaining in all of nonbank credit provision. And even now, bankers are trying to roll back what rules do exist.

Defenders of the status quo ignore the fundamental questions raised by the fact that shocks have required the Fed to repeatedly prop up short-term credit markets.

In the wake of each of the episodes of turmoil in shadow lending, we have avoided asking fundamental questions about the fragile structure of our financial markets. Is our economy best served by a financial system where billions of dollars in essentially “hot money” sloshes around in the good times, but seizes up at the hint of some disruption unless the government intervenes? Is it good for our society, more broadly, to use our central bank’s balance sheet solely to support banks, hedge funds, and other financial actors? Is this really the best system that we can design, or are there more democratic alternatives to the status quo?

- We could restrict the use of short-term obligations or give citizens direct access to Federal Reserve bank accounts.

- The Fed could lend to nonfinancial businesses, or financial guarantees could be paired with aid for struggling families and workers.

- We could subject all financial institutions that benefit from a government backstop—whether engaged in boring banking or shadow banking—to the same comprehensive level of regulation.

These reforms would not only make the economy more resilient. They would make sure everyone benefits from the Fed’s actions.

We made the choice to structure our financial markets this way, which means we also have the power to change them. It is time for us to stop conceiving of the financial markets, and especially short-term credit markets, as if they are the product of some immutable laws of physics. How many times will we let the plumbing of the financial markets get clogged before we ask if it’s time to finally replace the pipes?

Is Action of the Federal Reserve in the US Enough?

The US Federal Reserve will pump more than $1 trillion as it ramps up its market intervention as coronavirus melts down the economy.

- The Fed announced a bold new initiative in an effort to calm market tumult amid the coronavirus meltdown.

- In all, the new moves pump in up to $1.5 trillion into the financial system in an effort to combat potential freezes brought on by the coronavirus.

- This was the second day in a row and the third time this week the Fed has stepped in.

- Stocks staged a sharp turnaround from earlier losses, though some of those gains were pared.

“These changes are being made to address highly unusual disruptions in Treasury financing markets associated with the coronavirus outbreak,” the New York Fed said in an early afternoon announcement amid a washout on Wall Street that was heading toward the worst day since 1987.

Stocks were off their lows following the announcement though some of the gains were pared as the market digested the moves. Some in the market were skeptical that the move was enough, and even whether the the Fed itself had the proper tools to reverse the current market downtrend.

“We continue to emphasize that this Fed will act aggressively and in particular that central banks are focused on safeguarding market functioning at this point, and will continue to provide liquidity in scale,” Ebrahim Rahbari, director of global economics at Citi Research. “However, despite the sharp initial risk rally, we think these measures will still not be sufficiently to durably stabilize market sentiment yet in light of credit concerns and escalating health concerns.”

One part of the announcement saw the Fed widen the scale for its $60 billion worth of money the Treasury purchases, which to now had been confined to short-term T-bills.

Blunting The Impact And Hard Choices:

Early Lessons From China

From the International Monetary Fund: The impact of the coronavirus is having a profound and serious impact on the global economy and has sent policymakers looking for ways to respond. China’s experience so far shows that the right policies make a difference in fighting the disease and mitigating its impact – but some of these policies come with difficult economic tradeoffs.

Hard choices

Blunting The Impact And Hard Choices

To Watch in Europe

The Franco-German powerhouse took the helm of ongoing ambitions to modernize the EU’s trade defense system, with a joint letter to Malmström on “reforming” trade defense, sources in Berlin and inside the Commission confirmed. A spokesperson for the German economic ministry said, “We need to boost our trade defense measures by switching from an approach under which the Commission can only launch an investigation after a company claims to be discriminated, to a new scheme under which the Commission can take the initiative on its own,” he said. “And we need to speed up these investigations.”

Discussions among trade ministers will likely touch on the so-called “lesser duty rule,” which limits levying of duties on dumped imports and stalled the debate on EU trade defense in 2014. Originally, the goal was to eliminate this rule entirely, but this has been modified to abolishing it in certain circumstances only.

Some 546 MEPs voted in favor of the resolution, with 28 against and 77 abstentions. “This vote sends a strong signal that the European Parliament will not accept any measures that weaken our ability to defend ourselves from unfair Chinese competition,” said Socialist MEP David Martin, the lawmaker who pushed the resolution.

There are enough powerful countries on board for turning the EU-Canada deal into a “mixed agreement,” meaning that not only the Council and European Parliament, but also the national parliaments would have a say in approving it. However, the final decision is not expected before late June, after the Commission has said how it wants to apply the deal. And that’s the really interesting question.

Brussels exchanged long-awaited market access offers with the South-American trading bloc Wednesday, with the EU withdrawing its initially planned offer of a 78,000-ton beef quota and excluding ethanol. Both are described by the EU as “sensitive” areas, but might pop up later in the negotiations.

“Agricultural products are included in the offer the EU is making … just like beef, pork, dairy and grain,” said Rodolfo Nin Novoa, the foreign minister of Paraguay, which now holds the Mercosur presidency. “What’s not in there is the quota for beef, but [the offer] says they are determined to follow up on that, which gives us the certainty that this is part of the negotiation and we will obviously negotiate on that.”

Meanwhile, on the European side, other criticism remains. “It’s a first step excluding beef [quotas]. But we are still concerned about poultry, where lowering [import] restrictions towards Mercosur could have a detrimental effect for our agriculture industry,” a senior European diplomat said. Pekka Pesonen, secretary-general of the farmer’s lobby Copa-Cocega, criticized the Commission for including sensitive products in the offer “before any clarification was done in terms of removing red tape and other unnecessary non-tariff barriers to trade which stop our exports from entering these countries.”

Global Banking System Weak?

Stefan Gerlach writes: Eighty-five years ago this month, Credit-Anstalt, by far the largest bank in Austria, collapsed. By that July, banks in Egypt, Germany, Hungary, Latvia, Poland, Romania, and Turkey had experienced runs. A banking panic hit the United States in August, though the sources of that panic may have been domestic. In September, banks in the United Kingdom experienced large withdrawals. The parallels to the 2008 collapse of the US investment bank Lehman Brothers are strong – and crucial for understanding today’s financial risks.

For starters, neither the collapse of Credit-Anstalt nor that of Lehman Brothers caused all of the global financial tumult that ensued. Those collapses and the subsequent problems were symptoms of the same disease: a weak banking system.

In Austria in 1931, the problem was rooted in the breakup of the Austro-Hungarian Empire after World War I, hyperinflation in the early 1920s, and banks’ excessive exposure to the industrial sector.

Similarly, in 2008, the entire financial system was overextended, owing to a combination of weak internal risk management and inadequate government regulation and supervision. Lehman Brothers was simply the weakest link in a long chain of brittle financial firms.

Could a crisis like those triggered by the Credit-Anstalt and the Lehman Brothers collapse happen today? One is tempted to say no. After all, the global economy and the financial system appear to be on the mend; risk-taking in the private sector has been reduced; and huge, though burdensome, regulatory improvements have been undertaken.

The problem with this reasoning is that financial crises tend to reveal fault lines that were not visible before. Indeed, the financial sector manages the risks that it recognizes, not necessarily all the risks that it runs.

Unable to rule out a new crisis, how well are we equipped to cope with one? The short answer is: not very.

In fact, if a financial crisis were to occur today, its consequences for the real economy might be even more severe than in the past. Of course, because central banks now recognize that their responsibilities extend beyond stabilizing prices to include the prevention and management of financial tensions, they would undoubtedly be quick to respond to any shock with a battery of market operations. But, in the event of a crisis, the tools available to central banks to prevent deflation and a collapse of the real economy are severely constrained, especially today.

In the early twentieth century, central banks could all devalue their currencies against gold.. Today, however, currency depreciation is a zero-sum game.

Without the joint-depreciation option, central banks responded to the 2008 crisis with interest-rate cuts that were unprecedented in scope, size, and speed, as well as massive purchases of long-term securities (so-called quantitative easing, or QE). And those efforts were effective. But interest rates remain extremely low, and are even negative in some countries, and QE has been taken close to its limits, with public support for the policy waning. As a result, these tools’ ability to cushion an economy against further shocks is severely constrained. While forward guidance by central banks has also helped, it, too, is unlikely to be able to provide an effective buffer against a new shock.

How Monopolies Impact Income Inequality

Joseph Stiglitz writes: For 200 years, there have been two schools of thought about what determines the distribution of income – and how the economy functions. One, emanating from Adam Smith and nineteenth-century liberal economists, focuses on competitive markets. The other, cognizant of how Smith’s brand of liberalism leads to rapid concentration of wealth and income, takes as its starting point unfettered markets’ tendency toward monopoly.

For the nineteenth-century liberals individuals’ returns are related to their social contributions. Capitalists are rewarded for saving rather than consuming. Differences in income were then related to their ownership of “assets” – human and financial capital. Scholars of inequality thus focused on the determinants of the distribution of assets, including how they are passed on across generations.

The second school of thought takes as its starting point “power,” including the ability to exercise monopoly control or, in labor markets, to assert authority over workers. Scholars in this area have focused on what gives rise to power, how it is maintained and strengthened, and other features that may prevent markets from being competitive. Work on exploitation arising from asymmetries of information is an important example.

In the West in the post-World War II era, the liberal school of thought has dominated. Yet, as inequality has widened and concerns about it have grown, the competitive school, viewing individual returns in terms of marginal product, has become increasingly unable to explain how the economy works. So, today, the second school of thought is ascendant.

After all, the large bonuses paid to banks’ CEOs as they led their firms to ruin and the economy to the brink of collapse are hard to reconcile with the belief that individuals’ pay has anything to do with their social contributions.

In today’s economy, many sectors – telecoms, cable TV, digital branches from social media to Internet search, health insurance, pharmaceuticals, agro-business, and many more – cannot be understood through the lens of competition.

US President Barack Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers has attempted to tally the extent of increase in market concentration. The top ten banks’ share of the deposit market, for example, increased from about 20% to 50% in just 30 years, from 1980 to 2010.

Some of the increase in market power is the result of changes in technology and economic structure: consider network economies and the growth of locally provided service-sector industries. Some is because firms have learned better how to erect and maintain entry barriers, often assisted by conservative political forces that justify lax anti-trust enforcement and the failure to limit market power on the grounds that markets are “naturally” competitive. Large banks, for example, lobbied the US Congress to amend or repeal legislation separating commercial banking from other areas of finance.

The consequences are evident in the data, with inequality rising at every level, not only across individuals, but also across firms.

Joseph Schumpeter, one of the great economists of the twentieth century, argued that monopolies would only be temporary. There would be fierce competition for the market and this would replace competition in the market and ensure that prices Today’s markets are characterized by the persistence of high monopoly profits.

The implications of this are profound. If markets are based on exploitation, the rationale for laissez-faire disappears. Indeed, in that case, the battle against entrenched power is not only a battle for democracy; it is also a battle for efficiency and shared prosperity.

Wresting with Trade Issues

Dani Rodrik writes: The global trade system faces an important turning point at the end of this year, one that was postponed when China joined the World Trade Organization almost 15 years ago. The United States and the European Union must decide whether they will begin to treat China as a “market economy” in their trade policies.

China’s WTO accession agreement, signed in December 2001, permitted the country’s trade partners to deal with China as a “non-market economy” (NME) for a period of up to 15 years. NME status made it a lot easier for importing countries to impose special tariffs on Chinese exports, in the form of antidumping duties. In particular, they could use production costs in more expensive countries as a proxy for true Chinese costs, increasing both the likelihood of a dumping finding and the estimated margin of dumping.

Today, though many countries, such as Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and South Korea, have already rewarded China with market-economy status, the world’s two biggest economies, the US and the EU, have not.

Economists have never been fond of the WTO’s antidumping rules. From a strictly economic standpoint, pricing below costs is not a problem for the importing economy as long as the firms that engage in the strategy have little prospect of monopolizing the market. That is why domestic competition policies typically require evidence of anti-competitive practices or the likelihood of successful predation. Under WTO rules, however, pricing below costs on the part of exporters is sufficient for imposing import duties, even when it is standard competitive practice – such as during economic downturns.

This and other procedural considerations make antidumping the preferred route for firms to obtain protection from their foreign rivals when times are tough. The WTO does have a specific “safeguard” mechanism that enables countries to raise tariffs temporarily when imports cause “serious injury” to domestic firms. But the procedural hurdles are higher for safeguards, and countries that use them have to compensate adversely affected exporters.

The global trade regime has to address issues of fairness, in addition to economic efficiency. When domestic firms must compete with, say, Chinese firms that are financially supported by a government with deep pockets, the playing field becomes tilted in ways that most people would consider unacceptable. Certain types of competitive advantage undermine the legitimacy of international trade, even when (as with this example) they may imply aggregate economic benefits for the importing country. So the antidumping regime has a political logic.

Trade policymakers are deeply familiar with this logic, which is why the antidumping regime exists in its current form, enabling relatively easy protection. What trade officials have never taken on board is that the fairness argument extends beyond the dumping arena.

If it is unfair for domestic firms to compete with foreign entities that are subsidized or propped up by their governments, is it not similarly unfair for domestic workers to compete with foreign workers who lack fundamental rights such as collective bargaining or protections against workplace abuse? Aren’t firms that despoil the environment, use child labor, or provide hazardous employment conditions also a source of unfair competition?

Such concerns about unfair trade lie at the heart of the anti-globalization backlash. Yet legal trade remedies permit little room for them beyond the narrow commercial realm of below-cost pricing. Labor unions, human rights NGOs, consumer groups, or environmental organizations do not have direct access to protection in the way that firms do.

Trade experts have long been wary of opening up the WTO regime to questions about labor and environmental standards or human rights, fearing the slippery slope of protectionism. But it is becoming increasingly clear that excluding these issues does greater damage. Trade with countries that have very different economic, social, and political models raises genuine concerns about legitimacy. Refusal to acknowledge such concerns not only undermines these trade relationships; it also jeopardizes the legitimacy of the entire global trade regime.

None of this implies that democracies should not trade with non-democracies. The point is that commercial logic is not the only consideration that should govern their economic relationships. We cannot escape – and therefore must confront – the dilemma that gains from trade sometimes come at the expense of strains on domestic social arrangements.

Public discussion and deliberation are the only way that democracies can sort out the contending values and tradeoffs at stake. Trade disputes with China and other countries are an opportunity for airing – rather than repressing – these issues, and thus taking an important step toward democratizing the world’s trade regime.

Obama Tackles Financial Transparency Issues

That is why President Obama is calling on Congress to take four critical actions to strengthen what the U.S. can do about exploitation of the financial system.

1. Pass legislation to require “beneficial ownership” transparency: On behalf of the Administration, the U.S. Department of the Treasury is sending a new legislative proposal to Congress that would require all companies formed in the U.S. report information about their beneficial owners to the Department of the Treasury. That step would make information about beneficial owners readily available to law enforcement.

2. Pass legislation to give law enforcement better anti-corruption tools: We are also seeking legislation to advance our ability to fight corruption both here in the United States and abroad. The new legislative proposals would enhance the ability of our law enforcement officials to obtain information from domestic and foreign banks so they can investigate and prosecute money laundering. This will also allow the Justice Department to prosecute money laundering linked to a broader set of crimes, including ones that involve corrupt public officials.

3. Approve eight tax treaties: Eight tax treaties have been awaiting Senate approval for several years. Without those treaties, U.S. officials don’t have a complete set of tools to fully investigate and crack down on tax evasion by Americans with offshore accounts, including secret Swiss bank accounts.

4. Strengthen existing law to improve reciprocal transparency: In 2010, President Obama signed legislation that established the global standard for financial reporting by requiring foreign financial institutions to automatically report to the IRS information about financial accounts held by U.S. persons. But right now, the U.S. doesn’t provide the same information to its partners under this law that they provide to the United States. Congress can strengthen this law by requiring U.S. financial institutions to provide that information to our partners.

Why Are Central Banks Under Fire?

Howard Davies writes: Central banks have been on a roller-coaster ride in the last decade, from heroes to zeroes and back again. Is another downswing in their fortunes and reputations now starting?

In 2006, when Alan Greenspan retired after his 18-year reign as Chair of the US Federal Reserve Board, his reputation could hardly have been higher. He had steered the US economy through the dot-com boom and bust, had carefully navigated the potential threat to growth from the terror attacks of September 11, 2001, and presided over a period of rapid GDP and productivity growth. At his final Board meeting, Timothy Geithner, then-President of the New York Fed, delivered what now seems an embarrassing encomium, saying that Greenspan’s stellar reputation was likely to grow, rather than diminish, in the future.

The early reactions by central banks to the deepening financial crisis in 2008 were unsure. The Bank of England (BoE) lectured on moral hazard while the banking system imploded around it, and the European Central Bank continued to slay imaginary inflation dragons when almost all economists saw far greater risks in a eurozone meltdown and associated credit crunch.

Yet, despite these missteps, when governments around the world considered how best to respond to the lessons of the crisis, central banks, once seen as part of the problem, came to be viewed as an essential part of the solution. They were given new powers to regulate the financial system, and encouraged to adopt new and highly interventionist policies in an attempt to stave off depression and deflation.

Central banks’ balance sheets have expanded dramatically, and new laws have strengthened their hand enormously. In the United States, the Dodd-Frank Act has taken the Fed into areas of the financial system which it has never regulated, and given it powers to take over and resolve failing banks.

In the United Kingdom, bank regulation, which had been removed from the BoE in 1997, returned there in 2013, and the BoE also became for the first time the prudential supervisor of insurance companies – a big extension of its role. The ECB, meanwhile, is now the direct supervisor of more than 80% of the European Union’s banking sector.

In the last five years, central banking has become one of the fastest-growing industries in the Western world. The central banks seem to have turned the tables on their critics, emerging triumphant. Their innovative and sometimes controversial actions have helped the world economy recover.

But there are now signs that this aggrandizement may be having ambiguous consequences. Indeed, some central bankers are beginning to worry that their role has expanded too far, putting them at risk of a backlash.

There are two related dangers. The first is encapsulated in the title of Mohamed El-Erian’s latest book: The Only Game in Town. Central banks have been expected to shoulder the greater part of the burden of post-crisis adjustment. Their massive asset purchases are a life-support system for the financial economy. Yet they cannot, by themselves, resolve the underlying problems of global imbalances and the huge debt overhang. Indeed, they may be preventing the other adjustments, whether fiscal or structural, that are needed to resolve those impediments to economic recovery.

This is particularly true in Europe. While the ECB keeps the euro afloat by doing“whatever it takes”, governments are doing little. Why take tough decisions if the ECB continues to administer heavier and heavier doses from its monetary drug cabinet?

The second danger is a version of what is sometimes called the “over-mighty citizen” problem. Have central banks been given too many powers for their own good?

Quantitative easing is a case in point. Because it blurs the line between monetary and fiscal policy unease has grown. We can see signs of this in Germany, where many now question whether the ECB is too powerful, independent, and unaccountable. Similar criticism motivates those in the US who want to “audit the Fed” – often code for subjecting monetary policy to Congressional oversight.

There are worries, too, about financial regulation, and especially central banks’ shiny new macroprudential instruments. I

Others, notably Axel Weber, a former head of the Bundesbank, think it is dangerous for the central bank to supervise banks directly. Things go wrong in financial markets, and the supervisors are blamed. There is a risk of contagion, and a loss of confidence in monetary policy, if the central bank is in the front line.

That points to the biggest concern of all. Central banks’ monetary-policy independence was a hard-won prize. It has brought great benefits to our economies. But an institution buying bonds with public money, deciding on the availability of mortgage finance, and winding down banks at great cost to their shareholders demands a different form of political accountability.

The danger is that hasty post-crisis decisions to load additional functions onto central banks may have unforeseen and unwelcome consequences. In particular, greater political oversight of these functions could affect monetary policy as well. For this reason, whatever new mechanisms of accountability are put in place will have to be designed with extraordinary care.