Is the dollar going to rise?

Anatole Kaletsky writes: The US Federal Reserve is almost certain to start raising interest rates when the policy-setting Federal Open Markets Committee next meets, on December 16.

Janet Yellen, the Fed chair, has repeatedly said that the impending sequence of rate hikes will be much slower than previous monetary cycles, and predicts that it will end at a lower peak level. There is good reason to believe that the Fed’s commitment to “lower for longer” interest rates is sincere.

The Fed’s overriding objective is to lift inflation and ensure that it remains above 2%. To do this, Yellen will have to keep interest rates very low, even after inflation starts rising.

In the 1980s, Volcker’s historic responsibility was to reduce inflation and prevent it from ever rising again to dangerously high levels. Today, Yellen’s historic responsibility is to increase inflation and prevent it from ever falling again to dangerously low levels.

Under these conditions, the direct economic effects of the Fed’s move should be minimal. It is hard to imagine many businesses, consumers, or homeowners changing their behavior because of a quarter-point change in short-term interest rates, especially if long-term rates hardly move.

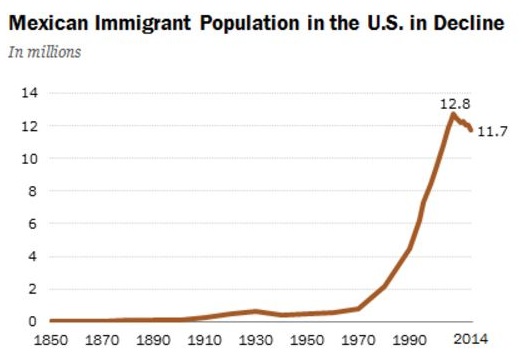

Many Asian and Latin America countries, in particular, are considered vulnerable to a reversal of the capital inflows from which they benefited when US interest rates were at rock-bottom levels. But, as an empirical matter, these fears are hard to understand.

The imminent US rate hike is perhaps the most predictable, and predicted, event in economic history.

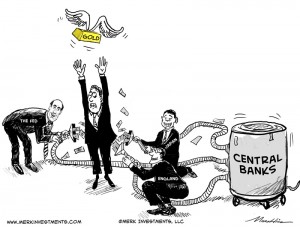

What about currencies? The dollar is almost universally expected to appreciate when US interest rates start rising, especially because the EU and Japan will continue easing monetary conditions for many months, even years. This fear of a stronger dollar is the real reason for concern, bordering on panic, in many emerging economies and at the IMF. Fortunately, the market consensus concerning the dollar’s inevitable rise as US interest rates increase is almost certainly wrong, for three reasons.

First, the divergence of monetary policies between the US and other major economies is already universally understood and expected. Thus, the interest-rate differential, like the US rate hike itself, should already be priced into currency values.

Moreover, monetary policy is not the only determinant of exchange rates. Trade deficits and surpluses also matter, as do stock-market and property valuations, the cyclical outlook for corporate profits, and positive or negative surprises for economic growth and inflation. On most of these grounds, the dollar has been the world’s most attractive currency since 2009; but as economic recovery spreads from the US to Japan and Europe, the tables are starting to turn.

Finally, the widely assumed correlation between monetary policy and currency values does not stand up to empirical examination. In some cases, currencies move in the same direction as monetary policy – for example, when the yen dropped in response to the Bank of Japan’s 2013 quantitative easing. But in other cases the opposite happens, for example when the euro and the pound both strengthened after their central banks began quantitative easing.

For the US, the evidence has been very mixed. Looking at the monetary tightening that began in February 1994 and June 2004, the dollar strengthened substantially in both cases before the first rate hike, but then weakened by around 8% (as gauged by the Fed’s dollar index) in the subsequent six months. Over the next 2-3 years, the dollar index remained consistently below its level on the day of the first rate hike. For currency traders, therefore, the last two cycles of Fed tightening turned out to be classic examples of “buy on the rumor; sell on the news.”

Of course, past performance is no guarantee of future results, and two cases do not constitute a statistically significant sample. Just because the dollar weakened twice during the last two periods of Fed tightening does not prove that the same thing will happen again.