During the early Depression years, unemployment peaked at 25%. U.S. economic output plunged nearly 30%. Thousands of banks failed. Millions of homeowners faced foreclosure. Businesses failed.

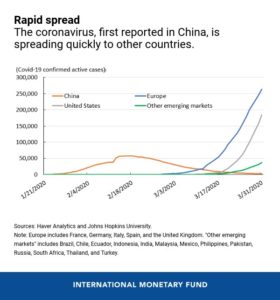

No one knows how this recession may unfold or how effectively the government’s rescue programs might help. Ignited by an external event – a raging global pandemic – it is uniquely different from both the Depression and the financial meltdown of 2008-09. And so its possible solutions are trickier.

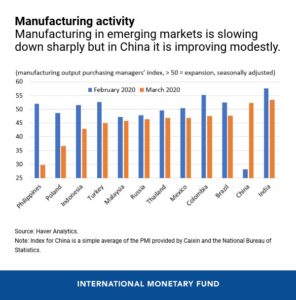

It isn’t a conventional dislocation rooted in a financial collapse or an overheated economy or a burst asset bubble. The twist this time is that the only sure way to defeat the pandemic – with drastic containment measures like lockdowns, quarantines and business closures – is to deliberately cause a recession by bringing business and social life to a halt.

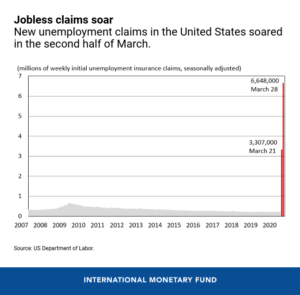

James Bullard, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, has gone so far as to warn that unemployment could reach 30% within months and that economic output could shrink 50%. Other outlooks aren’t quite as grim. But they’re all bleak.

Some economists take heart from the fact that the government possesses more potent tools to stabilize the economy than it did in the 1930s, some of them created in response to the Depression. They include a social safety net in unemployment insurance, a guarantee of bank deposits and federally backed mortgages. And the 2008 financial crisis led to the creation of an array of programs to fortify the banking system and encourage borrowing and spending.

President Donald Trump, after a hesitant start, now backs a bold and multi-pronged federal response to the crisis. It is just the sort of sweeping government involvement in the economy that was pushed this year by Democratic presidential candidates, well before the viral outbreak, but is almost always resisted by Trump and other Republicans.

After days of negotiations between congressional leaders and White House officials, Congress edged toward an agreement Tuesday on legislation that would deliver, by far, the largest economic rescue plan in U.S. history. At somewhere around $2 trillion, the wide-ranging aid package is intended to sustain workers and companies for at least 10 weeks. After that, further help might be needed.

The final package is expected to include, among other things, one-time cash payments of $1,200 to individuals and $3,000 for a family of four; more generous unemployment benefits for workers sidelined by the virus; an extension of that coverage to gig workers and independent contractors; and small business loans to help retain workers. An earlier $100 billion-plus package passed by Congress last Wednesday and signed by Trump includes a guarantee of paid sick leave for some workers affected by the virus.

A major element of the government’s intervention will continue to be the Federal Reserve, which is injecting trillions of dollars in liquidity into the financial system to support key lending programs. On Monday, the Fed unleashed its boldest effort yet to protect the U.S. economy by helping companies and governments pay their bills. With lending markets threatening to shut down, the Fed’s intervention is intended to ensure that households, companies, banks and governments can get the loans they need at a time when their own revenue is drying up.

As a whole, the emerging all-guns-blazing federal response is at least an echo of the economic stimulus that Roosevelt engineered in the depths of the Depression. Huge government aid programs put tens of millions to work in the construction of public buildings and roads, the pursuit of conservation projects and development of the arts.

Rural poverty was addressed, in part, by buying low-producing land owned by poor farmers and resettling them in group farms. Fannie Mae was created to buy home mortgages issued by the Federal Housing Administration. After the immediate crisis passed, Congress enacted far-reaching reforms of the financial system and banks and established unemployment insurance.

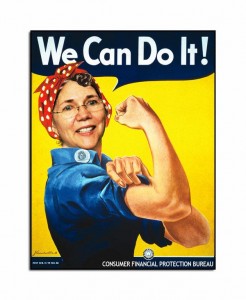

In contrast to today, the 1930s workforce was predominantly a male-dominated one of manual and farm labor. That changed only later, when the “Rosie the Riveter” wave of women entered factories to help mobilize America to fight World War II – a mobilization whose economic boost finally ended the Depression.

Today’s service sector-dominated 21st century economy, populated more by retail, technology and financial services as well as by contractors, freelancers and “gig” workers, is far different. A 2020 equivalent of the Works Progress Administration would be hard to imagine.

In today’s environment, more likely than government-created jobs are temporary measures like cash payments and guaranteed paid sick leave. Yet the options for the government are so vast that experts say they could deliver a significant benefit if deployed properly.

“There are more levers now for the government,” says Richard Grossman, who teaches economic and financial history at Wesleyan University. “There’s a lot now that the government can do that it wouldn’t even have thought of doing in the 1930s.”

An example was a rarely used 1950s-era lever that Trump invoked last week – the Defense Production Act. It empowers the government to marshal private industry to accelerate production of key supplies in the name of national security. (Critics complain that Trump has yet to put the law fully into action by actually ordering companies to make protective masks and other equipment that hospitals say are running dangerously low.)

Also last week, the president said he was open to giving the government a vast reach into the private sector – by taking equity stakes in companies that have been crippled by the virus, in exchange for giving the companies emergency loans.

This would recall the 2008-09 financial crisis, when the government engineered a $700 billion bailout of banks and automakers – and, in exchange, acquired equity stakes in those companies. That enabled the government to profit years later, when the companies repaid the taxpayer bailouts. The government took over outright the home mortgage backers Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

“Right now, the country’s frozen,” said Anat Admati, a professor of finance and economics at Stanford University and senior fellow at Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research. “Policymakers have to decide what’s really best for society.”

Admati notes that FDR’s New Deal and unemployment insurance wove a new safety net after the ravages of the Depression. But the net has eroded over the last decade, she says, along with the rise in gig and part-time workers and low-paid staffers in health care and other service industries. Many of those workers don’t stand to benefit much, if at all, from unemployment benefits and other programs built for a different era.

A result is that income inequality could worsen as a result of the crisis and the economic and social dislocation it causes.

“There are bailouts and subsidies coming,” Admati said. “The key is how they are targeted.”

–