The St. Louis Federal Reserve reports: With nearly four million jobs open in the U.S., almost two million in Europe and an estimated 85-million worldwide worker shortage by 2020,] the US is not alone in the charge to create workforce systems that better reflect the needs of the global workforce. The solutions to solving many of these issues go well beyond the borders of a singular community, state or nation.

Adding to the complexity of instituting effective workforce development programs is the paradigm between the global workforce shortage and technological advancements that threaten to displace many workers. Technology may be able to decrease a future global shortage by automating many of the jobs that are currently unfilled, but there is a need to ensure there are adequate jobs for people in the labor force.

The authors of an Oxford University report distinguish between jobs that are routine and those that are non-routine, which require more cognitive skills. The more creative intelligence a job requires, the less likely it is to be done by a computer. The report analyzes 702 occupations and categorizes them by the potential to be automated: low, medium and high-risk. Interestingly, the authors predict that computerization will reduce the demand for low-skill and low-wage jobs in the near future rather than middle-income occupations, which has been the recent pattern.

In a more global economic system with so many constantly shifting factors, it is difficult to determine the types of jobs and technical skills that will be required for future generations.

Foreign Direct Investment in the U.S.: Top 15 FDI Stock Positions, 2012

| Rank |

Country |

% of Total Investment ($2.7 Trillion) |

U.S. Dollars (in Billions) |

| 1 |

United Kingdom |

21% |

$564.7B |

| 2 |

Japan |

12% |

$309.4B |

| 3 |

Germany |

10% |

$272.3B |

| 4 |

Canada |

10% |

$261.1B |

| 5 |

France |

8% |

$221.7B |

| 6 |

Netherlands |

5% |

$130.1B |

| 7 |

Ireland |

5% |

$127.7B |

| 8 |

Switzerland |

5% |

$126.0B |

| 9 |

Spain |

2% |

$51.9B |

| 10 |

Australia |

2% |

$51.1B |

| 11 |

Belgium |

2% |

$47.7B |

| 12 |

Sweden |

2% |

$41.4B |

| 13 |

Italy |

1% |

$33.2B |

| 14 |

Norway |

1% |

$30.8B |

| 15 |

Mexico |

1% |

$29.2B |

Since Germany is one of the top investors in the U.S. for FDI, they want to ensure a future pipeline of skilled American workers. German manufacturing companies have identified finding and retaining workers with the right skills as the biggest challenge for German companies operating in America. One of the international workforce programs gaining attention in the U.S. is the German dual vocational education system, which focuses on youth employment and occupational certifications through education and apprenticeships for over 330 occupational competencies.

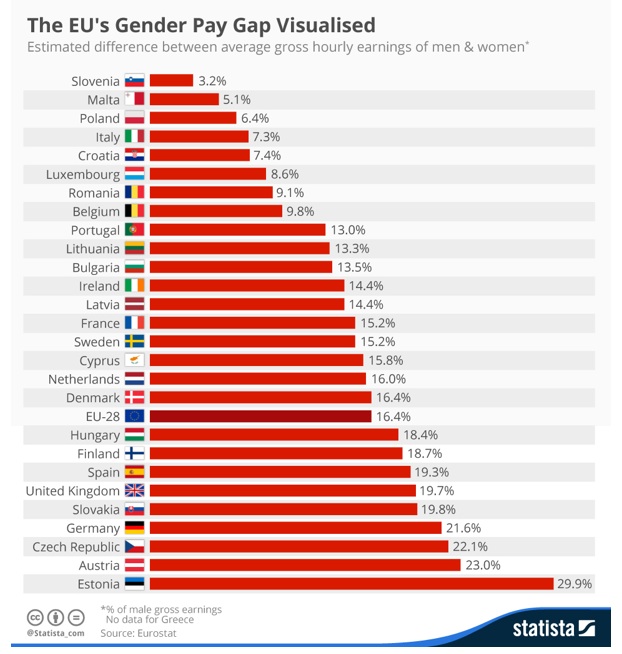

In the U.S., 0.2 percent of the labor force work as apprentices compared with 3.7 percent of the German workforce. German apprentices are mostly high school students between the ages of 16 and 19; the median age for an American apprentice is 26. Additionally, youth unemployment levels in 2014 were lower in the countries that have adopted the German system (e.g., Austria, Germany, Switzerland) compared with other European countries in the region near Germany and with the U.S.

TABLE 2

2014 Youth Unemployment Levels

| Country |

Youth Unemployment |

| Spain |

53.2% |

| France |

24.2% |

| Ireland |

23.9% |

| Poland |

23.9% |

| Belgium |

23.2% |

| United Kingdom |

16.9% |

| Czech Republic |

15.9% |

| United States |

14.3% |

| Netherlands |

12.7% |

| Austria |

10.3% |

| Switzerland |

8.6% |

| Germany |

7.7% |

Another characteristic of the German system is involvement from the private sector. Industry helps to shape and redefine the list of occupational standards to ensure that they are the skills needed for the workforce. German companies pay for two-thirds of the costs associated with initial training for each apprentice – about 15,300 euros each year per trainee. This allows companies to improve their recruitment of qualified new employees, save on costs associated with training new hires, avoid hiring the wrong workers and better ensure that workers have the needed skills to perform in the workplace.

Many American cities and states are creating partnerships to integrate at least some aspects of the German system into their workforce development policies, especially in the manufacturing sector. According to The German Vocational Training System: An Overview, “As countries with strong internationally competitive economic, scientific and technological capacities, the USA and Germany have a strong strategic interest in the best concepts for qualification. Both countries design education and training based on the economic and societal demands of lifelong-learning, which focus on competencies and employability, as well as the promotion of transparent and transferable qualifications and the broadening of career paths.”[7] As this system continues to be adopted throughout the U.S., it is also important to look at other international workforce development systems that may have an impact in this country.

Many nations in Southeast Asia continue to have rapid economic growth and an ever-increasing need to ensure that their workers have the skills necessary to fill the jobs in many growth industries. According to Trading Economics, Singapore’s unemployment rate at the end of the second quarter of 2015 was 2 percent.[8] The rate has averaged only 2.48 percent from 1986 to 2015. From a workforce and economic development strategy, this situation shifts the focus from teaching skills to potentialworkers to improving the skills of existing workers to meet the demand for growth industries.

In 2015, Singapore announced new workforce strategies that place a strong emphasis on mid-career workers and ongoing learning to upskill current workers.[9] The Singapore Workforce Development Agency (WDA) is not just targeting workers in the trades, but also those in professional, management and even executive jobs. Ng Cher Pong, chief executive of WDA, explained, “The fundamental change under the sectoral manpower strategy is a much closer integration between economic development and manpower development. We are hoping through this process, it will pull the two much closer together and we have some of the conversations upfront, rather than have the economic development run ahead of the manpower development.”[9] As with the occupational standards in Germany, the sectoral manpower strategies in Singapore work with businesses, unions, educational institutions and government to identify the skills needed for the current and future workforce. The Singapore model will also use these standards to create “progression pathways” across an entire career with regard to the competencies and skills needed throughout various stages of a worker’s career.

Various global workforce development agencies are using particular standards of skills across industries to better align workers with the skills needed to compete for jobs and to narrow the workforce gaps that exist in some industries. Technology continues to help solve skills and workforce shortages, but at the same time threaten jobs of many workers worldwide. Additionally, the global nature of the evolving workforce creates opportunity and the need for workforce strategies that connect countries of investment to ensure workers have the skills for continued investment for economic growth. In a recent interview on Wharton Business Radio’s “Behind the Markets” with Jeremy Schwartz and Professor Jeremy Siegel, James Bullard, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, articulated the need for these alliances to improve the U.S. workforce. He said, “I think it would be a very good change in the national conversation to move toward talking about how can we improve productivity from the very low levels that it is today up to more reasonable growth rates that are consistent with historical trends and that would be the No. 1 thing that you could do for the U.S. economy over the medium term and the long term. I agree, though, that when you look at research on these questions, the human capital side of the U.S. does not look as good as it needs to. We need to get much better training and the right sort of training for the jobs that are actually going to be available and needed going forward.”